Summertime here in the West gets hot, real hot. But luckily, we had a pretty darn mild June after a crazy wet spring. When ground moisture starts higher in the beginning of the season than usual and warmer temperatures are late coming in, we often times get lulled to sleep by less plant stress. By mid-July when certain areas haven’t seen three days over 100 degrees many a farmer tries to save a few bucks by riding out the remaining heat until harvest. This is especially true in heat sensitive row crops like tomatoes or grape vineyards. However, on the nut tree side of things we usually only focus on Walnuts. It’s par for the course this time of year to see those great big majestic trees get covered in clays, polymers, sunscreens and reflectant products. We’ve seen it work well at times on vulnerable walnut species and save some hard-earned pennies on Serrs, Howards, Tulares and Chandlers. But what can we learn from newer research and past victories on all our nut crops?

Reducing Heat Stress

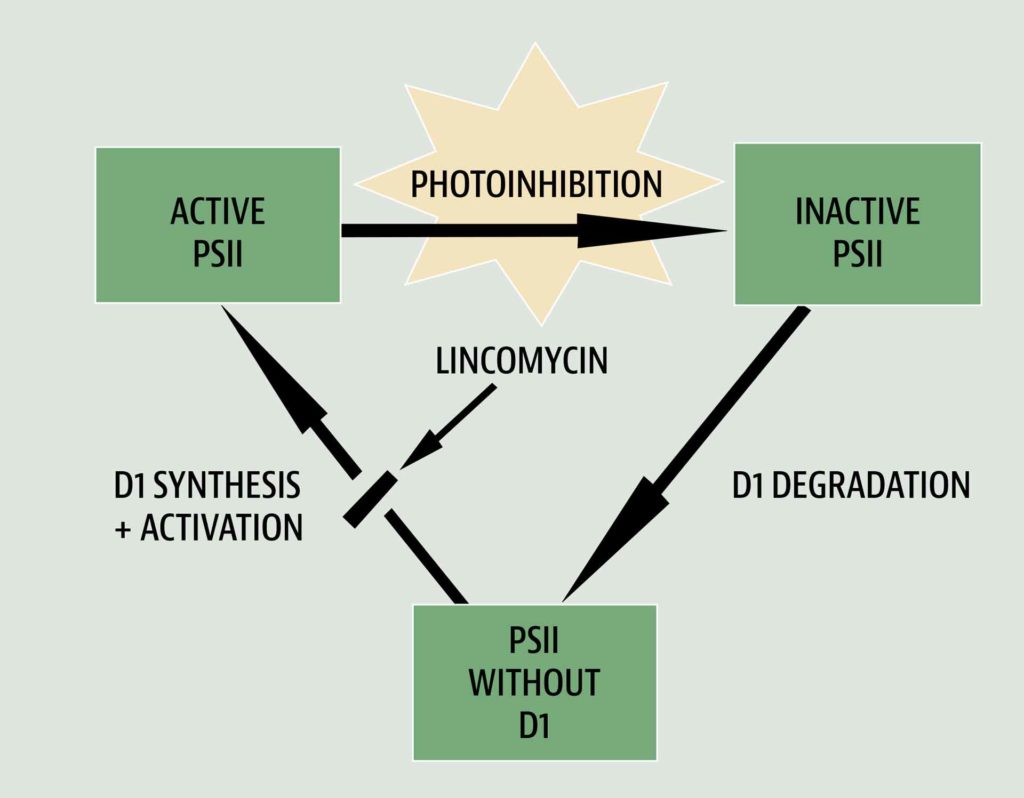

Many trees begin to shut down their transpiration potential when temps begin to climb over 85 degrees. Complete shutdown has been shown to occur with temps just in the low 90’s. As CCA’s (certified crop advisors), we have been trying for years to help reduce the effects of heat stress on all our crops through proper irrigation and nutrition. Research has shown that when plants hit their heat thresholds they close their stomata to conserve water and all transpiration stops. For every hour a plant is shut down, it can take two hours to recover. If a plant is shutdown during the day for eight hours, that’s 16 hours just for recovery, let alone resuming normal plant functions. We may actually be losing more yield than we think from just sunburn and staining. In speaking with an agronomist the other day, Robert Smith, he had done research on another phenomenon called photoinhibition. That discussion, a search of photoinhibition, a Wikipedia article, and a plethora of research papers got me to the Cliff Note version of the definition of photoinhibition:

“…Photoinhibition of photosynthesis is defined as a persistent decrease in the efficiency of solar energy conversion into photosynthesis in combination with a decreased overall capacity for photosynthesis. Environmental stresses that trigger photoinhibition include, for example, adverse temperatures, limited nutrient or water availability, and salinity.”

PHOTOSYNTHESIS AND PARTITIONING | Photoinhibition

B. Demmig-Adams, W.W. AdamsIII, in Encyclopedia of Applied Plant Sciences, 2003

Great. Another thing to worry about. Put plainly, we are most likely losing more during nut fill and heat stress than we think. If a plant doesn’t just shut down its transpiration, but also creates oxidative stress from too much sunlight, we may be drastically reducing our crops potential. At a seminar with David Doll, former University of California Cooperative Extension (UCCE) farm advisor for Merced County, he told me that a leaf only needs 30-45 minutes of sunlight to reach its capacity. Those upper canopy leaves get much more than that per day.

Reductions in Photosynthesis

Reductions in photosynthesis mean energy isn’t being stored and nutrients aren’t moving into the nuts. Our main storage centers for carbohydrates are not filling. Our plants are spending more energy for cellular repair than making our crop and filling the roots.

So, you’re at the beach in your new leopard print Speedo, you forgot sunscreen, bottled water and an umbrella… and mother nature turns up the heat. You know how you feel when you already have a sunburn and have to go back out into the sun? The same thing happens with plants. The higher the temperatures, the more photoinhibitory responses ramp up. It’s a double whammy.

Sunscreen for Your Trees

What do we do? Chasing deep moisture during later summer months is darn near impossible. We try to keep pulsing more frequent shots of water over our feeder roots and try to keep any deep moisture from subbing up. Ramp up your phosphorus (P) and potassium (K). Phosphorus is the key to the Krebs cycle and making Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (energy). Potassium (K) moves your nutrients through the plant while opening and closing the stomata. And don’t forget to put on sunscreen.

A great CCA and friend of mine, Dustin Stewart, has done a lot of research on different crop protection products. Most work to some degree, but some will inhibit stomatal activity once the plant cools back down. Others, have differing effects as to how they protect against solar damage. Do your research as to whether that shield for your crop is a clay, polymer, reflectant, refractant, or the latest and greatest invention from a Marvel movie, but put on some sunscreen. If you can keep a plants canopy cooler for an hour or so every morning when temps are rising and cool it off quicker at night when they go back down, that may be the game changer. Blocking out more UV light to reduce stress further will help you maximize your yields. You may not be able to control all oxidative and heat stressors, but being proactive will help keep you from getting burned.