Hull Rot is an infection in almonds caused by one of several pathogens. The infection not only causes quality and yield problems with the current crop, but it can impact the following season’s production.

Current Research

Current research findings, water and nitrogen management recommendations and chemical control options were reviewed by Mohammad Yaghmour, Kern County University of California Cooperative Extension (UCCE) advisor at the Almond Conference.

In addition to Yaghmour’s hull rot research, current information on the wood decaying fungi Ganoderma that affects almond tree health was provided by University of California (UC) Davis researcher David Rizzo and Bob Johnson, a University of California plant pathology PhD student who has studied wood decay fungi in almonds and prunes.

Hull Rot

Hull rot is a hull infection caused by one of several pathogens. Affected nuts don’t shake off at harvest and can become navel orangeworm (NOW) feeding sites if they are not removed in winter sanitation efforts. Infection of the hull can also result in death of the spur and attached shoot, reducing bearing surface of the tree.

The list of hull rot pathogens includes Rhizopus, Monilinia, Aspergillus and phomopsis. Yaghmour said Monilinia is found more often in the Sacramento Valley. It is spread by infected almond and stone fruit twigs, fruits and mummies. Rhizopus is a soilborne pathogen and is prevalent in the south San Joaquin Valley. Aspergillus niger is a soilborne pathogen. Hull rot infection produces fumaric acid which moves down spurs and shoots from the infected nut, leading to clumps of leaves wilting and sections of shoots or entire limbs dying. The dieback restricts the viability of fruiting wood, affecting the next year’s crop. Monilinia infections will cause hulls with a brown area on the outside and either tan fungal growth in the brown area on the inside or outside of the hull. Rhizopus infections cause black fungal growth on the inside of the hull between the hull and the shell. Aspergillus niger infections are characterized by flat jet-black spores between the hull and the shell.

According to the UC Davis integrated pest management (IPM) research the most susceptible varieties of almond are Nonpareil, Monterey and Wood Colony. University of California research, supported by the Almond Board of California is directing efforts to the newer pathogen—Aspergillus niger as well as continuing efforts to manage Monilinia and Rhizopus.

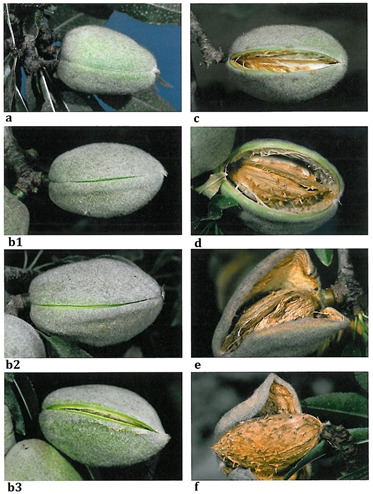

Yaghmour said that work done by UC Riverside researcher Jim Adaskaveg has determined the most susceptible time for nut infection is the deep V stage in hull development. Providing protection at that stage can reduce the incidence and severity of the disease.

Initial separation of the hull is when 50 percent or more of a thin separation line is visible. The deep V is when the suture is not yet visibly separated, but can be squeezed open by pressing both ends of the hull. Split is when the hull is open less than 3/8 inch.

Managing Hull Rot

There are also some cultural steps that can prevent outbreaks of hull rot in almond orchards.

Irrigation rates and humidity play large roles in hull rot infections. Yaghmour said he encourages use of a pressure bomb to determine water reduction. Moderate stress at the onset of hull split will increase hull split uniformity and reduce hull rot. Water reduction of 10-20 percent at the beginning of hull split and maintaining deficit irrigation for two weeks then returning to normal irrigation until harvest dry down is recommended.

Adaskaveg also worked on chemical control of hull rot, and determined that several fungicides have a good and reliable rating to control hull rot. Use of alkaline fertilizers was also found to be effective in controlling hull rot.

Hull rot caused by Rhizopus stolonifer can be managed by a single application of a fungicide at hull split (1-5 percent hull split) timed with the navel orangeworm insecticide treatment. Hull rot caused by Monilinia is best managed with fungicide applications three to four weeks before hull split.

The rate of applied nitrogen (N) also plays a role in hull rot infections. Dr. Patrick H Brown of the Plant Sciences Department at UC Davis said excess N increases hull susceptibility, increasing canopy humidity that favors fungal growth. Excess nitrogen also changes the fruit ripening and infection window.

Brown’s research showed that nitrogen added in excess of tree demand can result in enhanced tree vigor and enhance hull rot. There is also inefficient use of fertilizer and the potential for nitrate loss below the root zone.

Attempting to apply the majority of the annual N budget prior to June has the potential to increase nitrogen loss and to result in an overly vegetative shoot growth which encourages hull rot. Brown said that eliminating nitrogen applications from June through September risks limiting nitrogen availability to developing flower buds.

The most effective control for hull rot, he noted, is early harvest.

Ganoderma Root and Butt Rot

Ganoderma root and butt rot is another tree health concern for almond growers as it has been found in 68 orchards in the southern San Joaquin Valley.

Rizzo, plant pathologist at UC Davis and Johnson have been studying the spread of this wood rotting fungi in almonds and shared their findings about this emerging disease at The Almond Conference.

In trials and surveys in California almond orchards, Ganoderma was observed to be the most destructive fungi, causing trees to rot at the soil line and fall. There are four different species of Ganoderma. Johnson’s survey found that G. adspersum was the most destructive. Introduced in California only in the last few decades, G adspersum was found to kill young trees with four years the youngest and 14 being the average age. The infections result in orchard removal at less than half their life span.

Conks growing at the soil line on almond trees can be a sign that wood rotting fungi have attacked. Other signs are white rot and mycelium at infection sites. The fungus causes heartwood and sapwood to decay, reducing structural stability. Ganoderma is spread primarily by airborne spores and requires a wound to gain entrance.

Trees with Ganoderma infections show signs of general decline. There may also be a flat strip on the tree trunk or clefting at the graft union. Rizzo said that many infected orchards are first generation and have a high incidence of conks. These produce ‘astronomical” numbers of spores—12-40 million a day.

Rizzo said harvest and cultural practices play a part in the spread of Ganoderma in an orchard. Harvest and mummy shakes can cause wounds on the lower trunk and roots. Sweeping promotes spore dispersal in the orchard. Irrigation and winter rains assist spore percolation into soil and germination.

Cecilia Parsons

Cecilia Parsons has lived in the Central Valley community of Ducor since 1976, covering agriculture for numerous agricultural publications over the years. She has found and nurtured many wonderful and helpful contacts in the ag community, including the UCCE advisors, allowing for news coverage that focuses on the basics of food production.

She is always on the search for new ag topics that can help growers and processors in the San Joaquin Valley improve their bottom line.

In her free time, Cecilia rides her horse, Holly in ranch versatility shows and raises registered Shetland sheep which she exhibits at county and state fairs during the summer.