“Are growers applying too much nitrogen to their crops?”

This is a question Parry Klassen, director of the East San Joaquin Water Quality Coalition, looks to answer when discussing nitrogen, nitrates, groundwater quality and growing walnuts in a webinar hosted by West Coast Nut in July.

Klassen shared the principles of good nitrogen management, including the 4Rs—right time, right place, right amount and right source. As director of the East Joaquin Water Quality Coalition and executive director of the Coalition for Urban and Rural Environmental Stewardship (CURES), Klassen is right in the middle of the political environment regarding nitrates in groundwater and regulations placed by federal, state and regional government water agencies in California.

“There are many areas of the Central Valley where the groundwater has exceeded the nitrate drinking water standard,” he said.

Klassen noted this legacy issue of nitrate in the aquifers is something that can’t be changed and restored in the short-term, but is a long-term goal.

“But now, that is our situation, that is what we have to contend with,” he said.

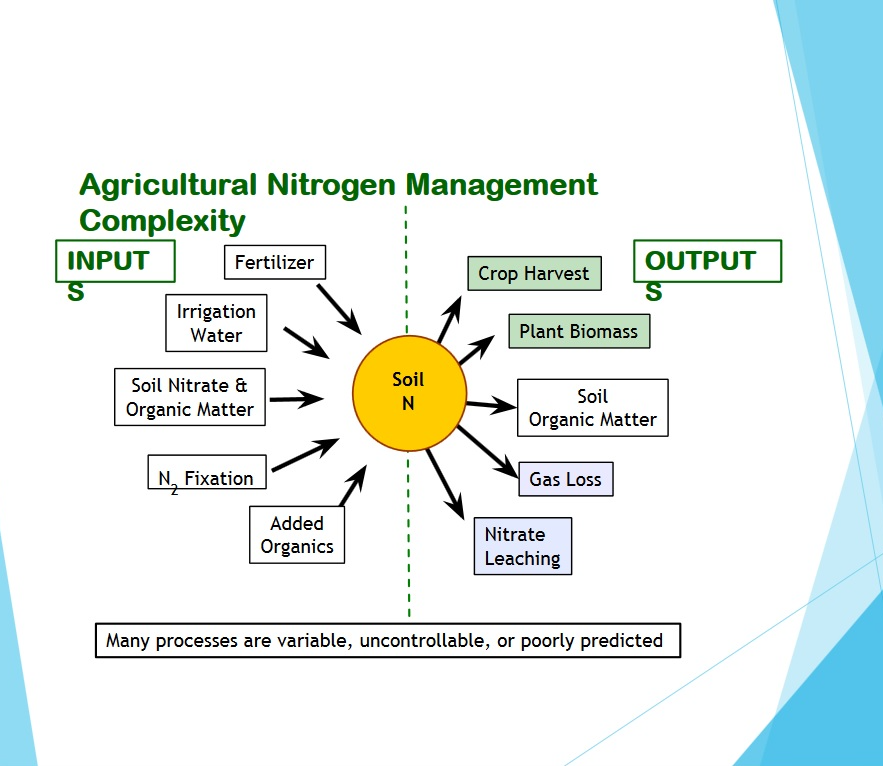

Nitrogen Management Complexity

Growers who have been studying nitrogen management over the years have come to realize the complexity of the matter, Klassen explained. Nitrogen is what growers apply to their orchards but nitrate is the molecule that makes its way into the groundwater.

“There are so many inputs of nitrogen in our systems for agriculture, such as fertilizers, many farms in areas have high nitrates in the groundwater, soil nitrates and organic matter, and these are all sources that our trees can use,” he said. “So, when we talk about nitrogen management, it is complex.”

Along with the nitrogen “inputs,” growers must consider “outputs”, such as harvested crop, plant biomass, soil organic matter, gas loss through the atmosphere, and nitrate leaching through rainfall and through irrigation beyond what the crop needs.

“This is where growers need to find a balance, between the inputs and the outputs,” Klassen said. “What we want to understand is the effective practices that can help reduce leaching, and at the same time provide the trees with the nitrogen they need.”

Klassen said understanding crop coefficients for fertilization in walnuts is an important key and something research is developing.

“Crop coefficients—we are going to hear a lot about the numbers related to this study through the rest of our careers,” Klassen said. “What crop coefficient numbers indicate is the amount of nitrogen it takes to efficiently grow a crop with little to no excess of nitrates leaching past the root zone into the groundwater.”

The crop coefficient is based on scientific studies using all tree parts to figure out what nitrogen is removed at harvest or at any growth stage of the tree.

“You can be assured that we, the researchers and organizations involved in this project, are putting a lot of money and effort into refining these nitrogen removed numbers because they are what will be used from the standpoint of determining the efficiency of how we are fertilizing and our performance as growers,” Klassen adds.

In the end, what the entire study and project comes down to, said Klassen, is using management practices to reduce leaching potential.

Right Time

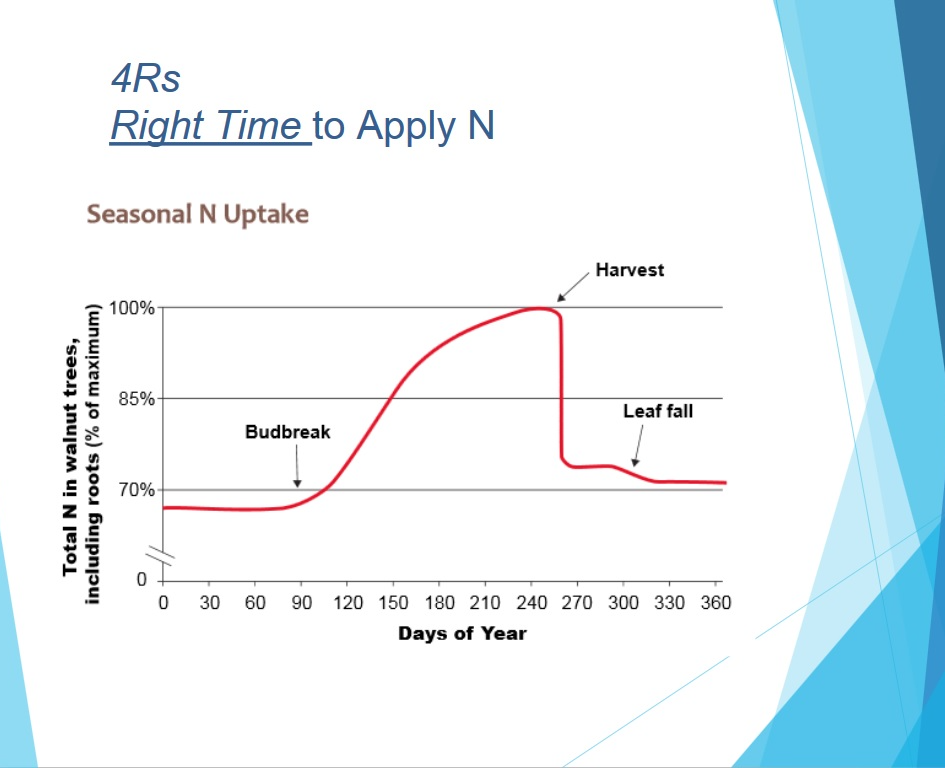

Starting with the “Right Time” of the 4 Rs, Klassen said the right time is “when the tree needs to be fertilized, when it needs the nitrogen, when is it hungry if you will, when will it take up the nitrogen.”

Crop consumption curves have been very helpful in learning when the right time is for nitrogen application in walnuts.

“What they have found in research is that the tree is really consuming a lot of nitrogen during fruit development early in the summer and clear up to before harvest,” Klassen said. “Studies have shown active root nitrogen uptake is pretty uniform in May, June, July and August, with the ideal to those split applications throughout the growing season.”

For example, 120 pounds of nitrogen/acre for a crop equals 40 pounds/acre/month through the growing season of May through July, and even an application in early August if the tree shows the need depending on tissue tests.

“Nitrogen used by a tree in April comes from storage in the tree’s structure from applications made the previous year,” Klassen added. “So applications made in March before trees are moving nitrogen can be a waste of money because if you get rainfall or you have a dry winter and need to irrigate, there is a very good chance you will leach that nitrogen applied in March or April into the groundwater.”

In addition, Klassen explains, trees do not efficiently take up nitrogen postharvest and late applications can lead to delayed dormancy or risk of leaching.

“The wrong time to apply nitrogen is in the wintertime when virtually none is taken up into the tree or roots,” he added. “And in early spring, very little nitrogen is taken up as most bloom/leaf expansion is coming through nitrogen stored in the tree’s wood.”

Right Rate

Klassen said a good source for calculating the right amount of nitrogen for application on walnuts can be found online at www.cdfa.ca.gov/go/FREPguide.

With many components taken into consideration, he added, the right rate is about 48 pounds/acre nitrogen per ton of walnuts/acre in-shell, taking into account eight pounds/acre nitrogen per acre lost to leaves/pruning, and 15 pounds/acre nitrogen per acre stored in woody tree parts.

Nitrogen required to grow a crop depends on:

- Yield potential (more yield=more nitrogen required.) It is important for growers to know a tree/orchard’s history to know its potential.

- Nitrogen sources are available to root systems.

- Efficiency that nitrogen is used by the tree.

“On top of all that, growers need to consider nitrogen available in irrigation water and organic amendments, such as compost, manure and cover crops,” Klassen said.

Leaf concentrations below 2.3% are indicative of nitrogen deficiency.

“Tree responsiveness to added nitrogen declines as leaf concentration increases between 2.3 and 2.7%. Adding nitrogen to provide leaf concentrations of 2.7% gives little or no yield response and causes nitrogen to accumulate in the soil,” Klassen adds.

Right Source

There are several forms of nitrogen fertilizers, each having different characteristics and behaving differently in the environment, some more mobile and leaching more readily into the groundwater.

“This is something to talk to your fertilizer supplier about, especially with urea and ammonium, as they both can be lost into the groundwater,” Klassen said. “Urea is mobile, but converts quickly to ammonium, which is less mobile, but ammonium quickly converts to nitrate by soil microorganisms in warm, moist soils.”

Urea and ammonium may also be lost through volatilization if surface is applied and not incorporated quickly. Nitrogen fertilization sources should be selected based on best root uptake to minimize excess nitrate movement past the root zone.

“Decisions on what nitrogen source to use is of course not just based on leaching, but also on cost and the ability to apply them in the drip system or broadcast,” Klassen said.

Right Place

“In general, the principle for the best place to apply nitrogen fertilizer is where the roots are, of course, and along the herbicide-cleaned strip,” Klassen said. “For tree-to-tree sprinkler irrigated orchards, many growers broadcast one or more applications, but remember, root systems develop where water is applied, so the best application method is fertigation, water run through sprinklers or micro-sprinklers by injecting fertilizer during last half of the set whether you do a 24-hour set or a 12-hour set. If at all possible, apply during the last half of the set, leaving 15 to 20 minutes at the end to adequately flush out the system of residue that could otherwise be sitting in the system when it is shut off.”

Studies performed over time have shown a dramatic leaching of nitrogen in flood irrigation systems when the fertilizer is applied and then six to eight inches of water are put on.

“Often, the nitrogen is pushed beyond the root systems in the orchard in these types of systems,” Klassen added.

He said a University of California study showed the majority of root growth is in the top 20 to 22 inches of soil.

“The vast majority of working roots are about between 7 to 18 inches down in the soil, so the principle of putting fertilization in the back half of the irrigation set places that fertilizer in the active roots where it is most efficiently going to be taken up,” Klassen said.

“One other thing I have to dwell on, as we have so many of our orchards in high groundwater nitrate areas, is growers need to be aware of the nitrogen levels in their irrigation water as this can be a useful source for crop production and the amount can be a pretty significant number. However, it is important to remember the caveat, that number is based on all 30 acre-inches in walnuts, for example, being absorbed by the tree through the year, and we know that is not likely.”