There’s a lot to consider before choosing the hazelnut variety, or varieties, to plant in a new orchard. Besides yield expectations, there’s also kernel versus inshell, harvest times, tree growth habits and a variety’s susceptibility to disease—especially to eastern filbert blight (EFB).

EFB was first discovered in the 1970s in western Washington. It moved into the Willamette Valley in the 1980s and has proven to be one of the most devastating diseases to hazelnuts. Since then, Oregon State University (OSU) has worked diligently to breed resistant hazelnuts in cooperation with Rutgers University in New Jersey, the University of Nebraska at Lincoln and the National Arbor Day Foundation.

OSU’s hazelnut breeding program formed in the late 1960s. Researchers and plant breeders there have collected hazelnut germplasm from around the world to develop new hazelnuts for the Pacific Northwest. So far, OSU plant breeder Shawn Mehlenbacher, along with Senior Research Assistants Rebecca McCluskey and David Smith, has come up with several EFB resistant varieties, including Jefferson, Yamhill and the very recent PollyO. All three varieties have the Gasaway gene, which imparts the blight resistance. The Gasaway variety is an obsolete pollinizer, but still extremely useful in the hazelnut breeding world.

Jefferson

Jefferson was released in 2009. It’s a good producer and a tidy, upright grower. A later variety than most, Jefferson leafs out in April instead of the more typical March. Once established, Jefferson takes less pruning to maintain its shape than most other varieties.

Jeff Newton, a hazelnut grower in the McMinnville, Ore. area and farm manager for Crimson West/Christensen Farms, grows a lot of Jefferson trees.

“It grows more up than out,” Newton said of Jefferson. “It’s precocious; it produces early.”

Jefferson trees are 30 to 40% smaller than Barcelona. They don’t have a tendency to lean.

Newton’s 11-year-old Jefferson trees are yielding well, although he has had some problems with mold at the processor.

Tangent, Ore. hazelnut grower Ryan Glaser likes the way Jefferson grows. He also likes the idea of a nut that is small enough to be sold inshell, yet large enough that it could also be marketed for kernel sales.

“In theory, Jefferson is a duel direction. The only inshell hazelnut OSU has come out with. It could go in two directions—inshell or kernel,” Glaser said. “Duel market hasn’t 100% worked out at the moment,” he admits, “but I think it will be better in the future. It did a little better last year.”

Glaser fertilizes his Jefferson trees just after leaves fall in late November and into December.

“The tree sucks nutrients out of the leaves, back into the wood, so we don’t waste any nutrients,” Glaser said about his fertilizer timing.

With the nutrient package that Glaser uses, it puts him at 43- to 44-percent crack-out weight. “That puts you in the mid-range kernel variety,” he said.

Some nuts tend to hang longer in Jefferson trees. Harvest, Glaser said, is three to seven days later than Barcelonas. “I don’t see that it’s an issue,” he said of the later drop.

When Jefferson nuts are mature, green husks are still persistent, according to research by Orchard Specialist Nik Wiman and others at OSU. Some of the nuts tend to hold on to the tree. Expect 95% of nut drop by Oct. 14 in the Pacific Northwest.

As far as mold, Glaser said that hasn’t been an issue for him. “We pick often and early,” he noted.

Mold issues could crop up with Jefferson if growers pick late, or if it’s a rainy harvest and the nuts sit in mud before being swept up.

Glaser learned the hard way about EFB on resistant varieties. He got a bad batch of Jefferson trees with EFB on the trunk. “Jefferson are resistant, but they’re still susceptible when they’re young,” Glaser said. Now he makes sure that his young trees have been treated with an EFB spray at the nursery.

Yamhill

Oregon State University released Yamhill in 2008. It’s sometimes called the upside-down tree because of its short and wide growth pattern. Yamhill is a less vigorous growing tree with flatter branch angles than Barcelona. Even though it’s a smaller tree than Barcelona, nut yield is greater.

Yamhill nuts are small and thin shelled with a fairly long period of nut drop. Nuts fall free of husks. Around the last 10% are stubborn, clingy nuts, according to Wiman. Expect 95% nut drop by September 26. Yamhill has a high tolerance to big bud mite infestation. Among the recommended pollinizers are York, Dorris, Wepster and Jefferson. Some years Yamhill sets a very heavy nut crop. Unfortunately, nuts in those years can be so poorly filled that the kernels are not suitable for market.

PollyO

PollyO was released in 2018, creating much excitement among hazelnut growers. PollyO is an alternative to Yamhill. It complements McDonald and Wepster, which were also bred at OSU.

“It’s a good producer, a kernel variety,” Newton said.

PollyO is a vigorous, globe-shaped tree with high nut yield. Nuts are small to medium in size, but larger than Yamhill and drop a few days earlier. Nuts are round with thin shells and are a blanching variety, meaning the brown skin, or pellicle, must be removed with heat. They mature early and have high kernel percentages.

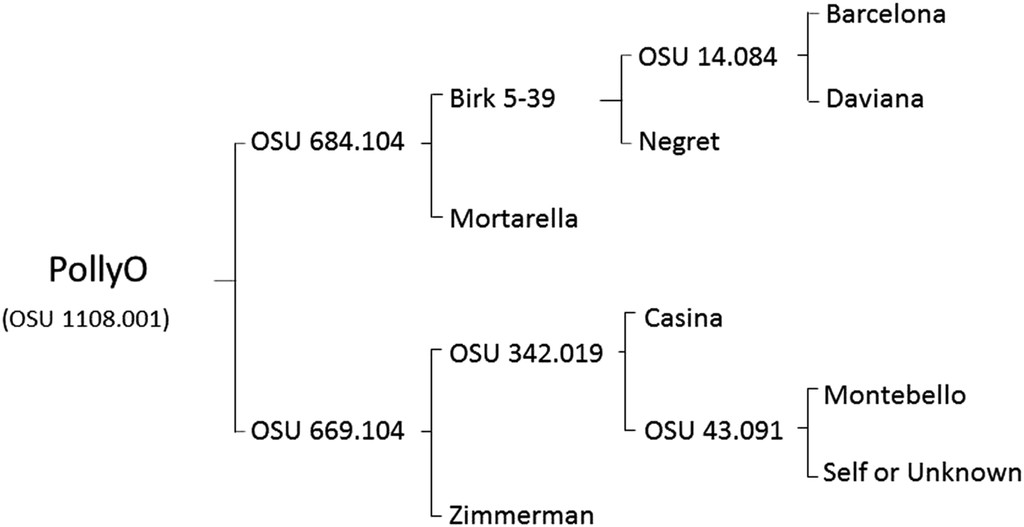

PollyO’s lineage comes from trees originating in Spain, Italy and England. It was named in honor of Polly Owen, who served as director of the hazelnut industry office from 1995-2018. During her years of service to the industry, Owen worked with university researchers, government officials, four industry organizations and hundreds of growers. Newton started some PollyO trees for Owen and gifted them to her so she could grow some of her namesake hazelnuts. Nurseries can obtain licensing agreements for PollyO from OSU, but sales are strictly limited to only the United States for the first four years after release.

According to OSU, PollyO nuts are in the range of 11 to 13 mm, which is the size preferred by major chocolate makers. Also noted by OSU is the early-season nut maturity—growers may cash in on the premium price offered by some hazelnut handlers for early nut delivery with PollyO. Early harvest before fall rains also equates to lower drying costs and higher nut yield.

In OSU trials from 2013-17, nuts of PollyO showed high percentages of good nuts, and low percentages of blanks, twins, poorly filled nuts, brown stain and kernels with black tips. Mold issues are similar in percentage to Jefferson. Kernel percent (kernel weight to nut weight) averaged 47% in trials.

It takes 18 years of testing before OSU releases a new variety. Most don’t make it. The university makes around 20,000 crosses a year, according to Newton. Maybe one of those makes it into the mainstream. OSU tests numbered varieties in Newton’s orchards. In 2019, he had approximately 50 trees being tested, with 15 different numbers. All of them, except the four which received the name PollyO, were removed at the end of that season.