In order to prevent herbicide damage in young trees, especially from postemergence herbicide, standard pomological practice has been to apply white latex paint to the bottom 2 to 3 feet of trunk of newly planted trees, before applying herbicides 1-5. While this may provide some level of protection 4-8, research to support this practice is lacking. In order to assess the efficacy of white latex paint in mitigating herbicide damage, a field experiment was conducted in Arbuckle, Calif., to evaluate the impacts of latex paint on herbicide injury in young almond trees.

Methods

To conduct this experiment, second-leaf almond trees were grouped into three categories: old paint (9-week old), new paint (2-day old), no paint (hardened-off for 9 weeks), and cartons. In June 2019, treatment combinations of different rates (see treatment table below) of glyphosate (Roundup PowerMAX), glufosinate (Rely 280), or a tank mix of both were applied. Each treatment combination had 4 replicates.

Herbicide applications were made using a CO2 backpack sprayer at 35 psi, and a spray volume of 20 gallons per acre. A single nozzle was held 18 inches from the trunk, moving vertically (from top to bottom) for one second on both the eastern and western sides of the trees.

In 2017, the block used to conduct this experiment was planted with greenhouse-grown trees. Each tree came with preinstalled cartons. Nine weeks before the herbicide applications for this experiment took place, the cartons for the “no paint” and “old paint” treatments were removed for the first time, exposing green bark. Valspar interior latex paint diluted 50:50 with water was then applied using a painter’s mitt to the group of trees in the old paint treatment. This also allowed for the no paint treatment to harden off for nine weeks prior to the herbicide application. Two days prior to the herbicide application, the cartons for the new paint treatments were removed for the first time (again, exposing green bark) and painted. The carton treatments in this experiment never had their cartons removed.

Evaluations

Evaluations across three categories of tree stress were taken on a weekly basis, starting three weeks after treatment (WAT) to allow symptoms to develop.

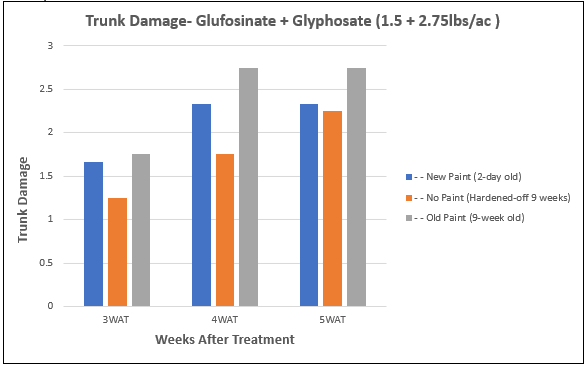

Trunk damage: Assessments made from 3WAT-5WAT quantified the number of individual gumming sites on each trunk (see Figure 1.) No further trunk gummosis was observed starting five weeks after the herbicide applications.

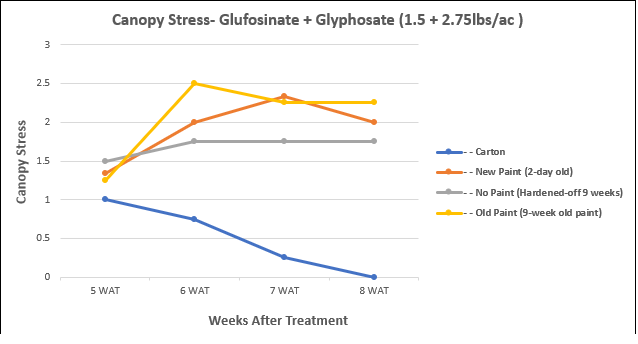

Canopy stress: Evaluations were taken from 5-8 WAT assessing the degree of interveinal chlorosis, mottled chlorosis, spotting, stacked internodes, necrosis and stem dieback

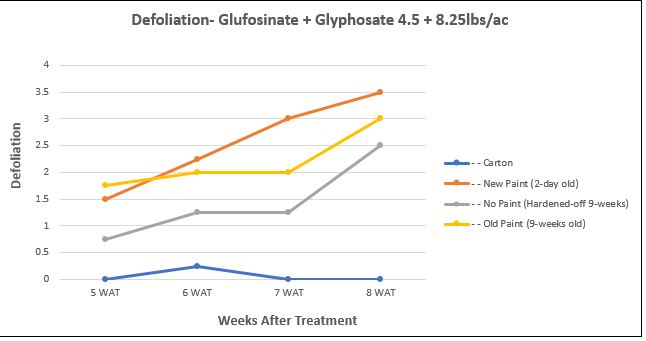

Defoliation: Ratings were taken from 5-8 WAT assessing the degree of defoliation for each tree (see Figure 2.)

Results

Preliminary results indicate that paint as a trunk protection method may not provide significant protection from glyphosate or glufosinate. Tree stress caused by trunk-applied herbicides was lowest in most treatments with no paint at all, which suggest that hardening of the bark is key to mitigating herbicide damage in young trees.

Trunk Damage:

Five weeks after herbicide treatments, data from the top-of-label-rate tank-mix application showed a 22% increase in trunk damage in trees with old paint, and a 4% increase in damage in trees with new paint, when compared to trees with no paint.

Canopy Stress:

Eight weeks after treatment, the label rate tank-mix applications showed a 29% increase in canopy stress in trees with old paint, and a 14% increase in damage was observed in trees with new paint, when compared to trees with no paint.

Defoliation:

Eight weeks after treatment, the high rate (3x) tank-mix applications showed a 40% increase in defoliation in trees with new paint, and a 20% increase in defoliation was observed in trees with old paint, when compared to trees without paint that were allowed to harden-off for 9 weeks.

Conclusion

Preliminary results indicate that in most treatment combinations, old and new paint as trunk protection methods did not reduce tree stress caused by trunk-applied herbicides. Allowing the bark of young almond trees to harden off for at least nine weeks reduced herbicide damage. The most efficacious trunk protection option for young almond trees is to install a carton, though remember when cartons are eventually removed green bark may be present and susceptible to herbicide injury. Therefore, as the trees mature and cartons are removed, allow the bark on trunks of trees to harden off to minimize herbicide damage.

References

-

- Moretti & Peachey, Pest Management Handbook-Pacific North West.pnwhandbooks.org/weed/horticultural/orchards-vineyards/vegetation-management-orchard-vineyard-berry

- MSU Extension, Chestnuts. Pest Management, Weeds. Michigan State University

http://www.canr.msu.edu/chestnuts/pest_management/weeds

- Parker, Michael, et al. “Growing Pecans in North Carolina.” NC State Extension Publications, NC State Extension, 15 June 2016, content.ces.ncsu.edu/growing-pecans-in-north-carolina.

- Rosenberger, Sudden Apple Decline: Trunk-Related Problems in Apples http://www.hort.cornell.edu/expo/proceedings/2017/TreeFruitPestMGMT.AppleTrunkDisorders.Rosenberger.2017.pdf

- Rothwell, Nikki, et al. “Glyphosate Damage in Apple and Cherry Orchards.” MSU Extension, 25 Sept. 2018, www.canr.msu.edu/news/glyphosate_damage_in_apple_and_cherry_orchards.

- Tianna DuPont, Weed Control Plots, Weed Management in Young Orchards.

http://extension.wsu.edu/chelan-douglas/agriculture/treefruit/pestmanagement/weedcontrolplots/

- Walgenbach, Tarpy, et al. “2020 Integrated Orchard Management Guide for Commercial Apples in the Southeast.” NC State Extension Publications , 4 Feb. 2020, content.ces.ncsu.edu/integrated-orchard-management-guide-for-commercial-apples-in-the-southeast.

- “Young Orchard Handbook.” University of California Agricultural and Natural Resources, UC Cooperative Extension Capitol Corridor, Mar. 2018, ccfruitandnuts.ucanr.edu/files/238596.pdf.