UC Davis Plant Sciences Professor Ken Shackel, who has spent much of his career working with the pressure chamber, thinks of the device as measuring the “blood pressure” of plants. Unlike blood pressure, which is taken when a person is resting, pressure chamber readings are taken during midday when the tree is most active in pulling moisture through the xylem into its leaves.

Although Shackel has been a staunch promoter of the device since the early 1990s, he said the industry has been slow to catch on. A recent survey by the California Department of Food and Agriculture’s Fertilizer Research and Education Program noted about 16% pressure chamber use in perennials.

“I’ve been saying, ‘This is a really good tool,’ but it’s really taken a lot of time to catch on,” he said. “The main resistance to it is people regard it as a scientific instrument and say it’s too detailed. There tends to be a little bit of bias against a monitoring tool that requires hand labor.”

The device’s utility wasn’t lost on second-generation nut grower Ryan Kaplan, who saw the pressure chamber put to use about eight years ago in a Butte County walnut orchard. The trees were suffering from Phytophthora and other health issues.

UCCE Farm Advisor Bill Olson, who has since retired, pulled leaf samples to analyze with the pressure chamber and found they were at -2 or -3 bars on a hot day – a sign of over-watering.

Kaplan said they had been using evapotranspiration and soil moisture probes to time the irrigations, but subsequently added pressure bomb readings.

“The pressure bomb tells you exactly how the tree is doing based on many scientific studies done by UC,” he said.

The following year, the orchard was much improved. During the next few years, yields climbed to 8,000 pounds per acre from 5,000 pounds per acre.

“At that point, I was sold on the benefits and started using it on all of our crops,” said Kaplan, whose family also grows almonds, pistachios and prunes. “But I was held back by the amount of time and effort it took to calculate and interpret all of the collected data for each orchard.”

To that end, he and a team developed the Pressure Bomb Express app that helps manage the information and produces an easy-to-use report.

A Complementary Tool

Allan Fulton, a UCCE Farm Advisor emeritus in Tehama County, has worked with Shackel and his research group on pressure chambers for more than two decades to expand their applications. Like many other tools in agriculture, Fulton said he doesn’t see it necessarily as a stand-alone, but instead as a complement to ET values and soil moisture sensor readings.

In addition, growers and orchard managers need to weigh their own experience irrigating specific blocks with pressure chamber results when deciding when to irrigate, he said.

Outside factors, such as forecast ET rates and well output, also may play into irrigation scheduling.

“You have to make some judgment calls on what’s going on, and that’s where there’s some art,” Fulton said. “With one year under your belt, you should start to figure out where the boundaries are.”

During this tenure, Fulton has seen increased use of pressure chambers, especially since the 2015 drought. Since 2000, UC studies that validated additional pressure chamber applications also aided adoption.

Wait to Irrigate

Take walnuts, for example. UCCE Integrated Orchard Management Walnut and Almond Specialist Bruce Lampinen and Shackel found many growers were irrigating too early in the spring, reducing the development of deep roots needed to mine water later in the season. As a result, trees had shallower root systems, and many that had yellow leaves were diseased.

By waiting to irrigate until the trees were mildly stressed based on pressure chamber results, typically mid- to late-June, the trees were healthier.

“I remember the first walnut meeting where we told growers we were waiting over a month to start (irrigation), and nothing happened to the trees,” Shackel said. “What’s been surprising in walnuts is the amount of time you can wait and actually let the soil dry out. In fact, it tends to have beneficial effects. It’s not even much stress early in the season. All we did was wait until we were showing just a little bit of stress – just -1 to -2 below baseline.”

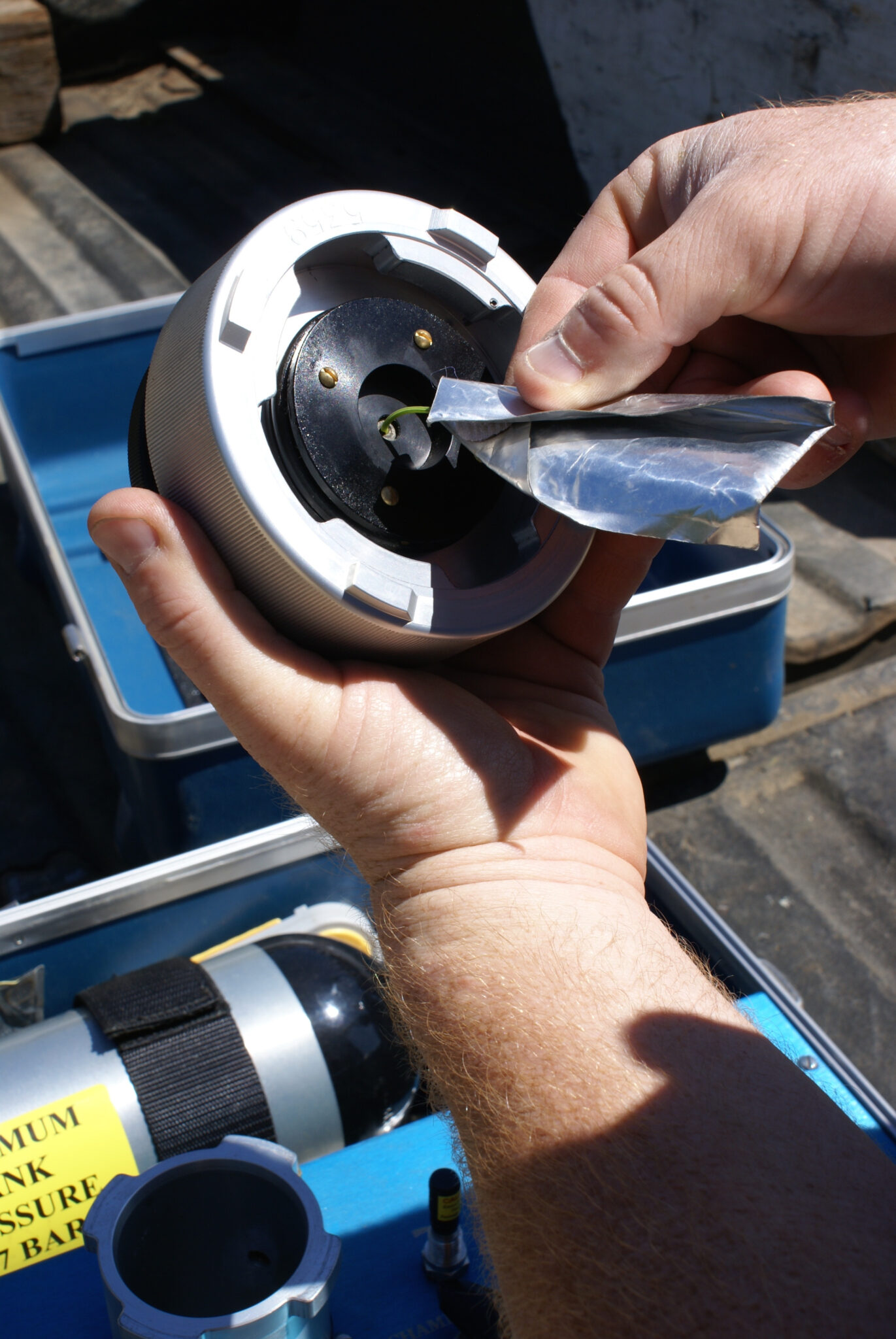

Pressure chambers aren’t used as much in pistachios because a latex-like sap complicates determining when the water just begins to appear at the cut edge of the petiole. But UCCE Orchard Systems Specialist Giulia Marino, who’s based at the Kearney Agricultural and Research Extension Center, is developing an easy fix to the issue.

What is a Pressure Bomb/Chamber?

A pressure chamber, also known as a pressure bomb, works by applying air pressure to a leaf inside the chamber. Only a small part of the leaf stem or petiole is outside the seal. The amount of pressure it takes to cause water to begin to appear at the cut edge of the petiole tells you how much water tension the leaf is experiencing.

The more pressure it takes, the higher the tension value and the higher the water stress. The readings are expressed as negative values, which can also be thought of as a water deficit. Researchers refer to this as the “stem water potential” or SWP when the leaf has been covered and prevented from losing water for at least 10 minutes before sampling.

A handful of companies manufacture pressure chambers, and they come in two basic models. The hand-pump relies on the user to manually increase the pressure within the chamber. Although it is cheaper to purchase, using it to sample multiple orchards may be too slow and not enable enough sampling, Fulton said.

As a result, most users favor pressure chambers that rely on a tank of welding-grade nitrogen to create the needed pressure.

Pressure Chamber Use in a Nutshell

Based on years of research, UC recommends sampling between noon and 4 p.m. when the tree is experiencing the greatest stress. Solar radiation, air temperature and relative humidity are also the most stable during this period.

Select trees that are representative of the orchard. They should be healthy, the same variety, the same size, have undergone the same pruning regimen and be planted on the same soil type as other trees. These same trees, which can be flagged, marked with paint or GPS-tagged, should be sampled throughout the growing season.

How often to sample depends on a number factors, including labor availability, orchard acreage and other cultural practices. Ideally, UC recommends sampling just before irrigation and then one to two days afterward to gauge how the trees have recovered. In almonds, select leaves that are in the interior shaded portion of the canopy. In walnuts, use leaves from the lower interior shaded portion of the tree.

Small Mylar or plastic bags are placed over the selected leaves while still on the tree for at least 10 minutes to allow for equilibration. Carefully cut the stem using a razor, knife or other sharp object. Place the stem end into the pressure chamber cap with ideally 1/8 to 1/4 inch sticking out. Then put the bagged leaf portion into the pressure chamber canister and tighten it into place.

As pressure is applied, watch the stem end for water just beginning to glisten on the cut end of the petiole. Shackel recommends using a hand lens with 7x magnification to help pinpoint when this occurs. The results are reported as negative bars.

SWP levels ranging from -4 to -8 in walnuts typically indicate low to moderate tree stress conditions. Low to mild SWP levels in almonds range from -10 to -14, while readings of -14 to -18 indicate moderate stress used during hull split to reduce hull rot and improve nut removal.

Environmental conditions, such as temperature and relative humidity, also affect what normal or “baseline” pressure chamber values would be in a fully irrigated orchard. UC has tables for download (http://bit.ly/3b1C9KF) that calculate baselines based on temperature and humidity. A website is also available (http://informatics.plantsciences.ucdavis.edu/Brooke_Jacobs/index.php) that provides these values for the last six days for any of the CIMIS weather station locations.

The growth stage during the season also will influence the amount of stress desired, particularly in almonds when moderate stress shortly before hull split reduces hull rot and promotes more even nut removal.

There’s an App for That

If these calculations seem confusing, you’re not alone. Kaplan, the second-generation nut producer, was in a similar boat when he expanded use of pressure bombs in their orchards more than four years ago.

He tried compiling pressure bomb results with baseline information, temperature, relative humidity and other factors in an Excel spreadsheet, only to find out it didn’t simplify matters.

“If it’s really hot and humid or really cool, the baseline will be different,” he said. “If you don’t figure in the baseline each time you take readings, the numbers that come out can really throw you off.”

The Pressure Bomb Express app he helped develop can be run on a smartphone or tablet. Users enter the temperature, relative humidity and pressure bomb result as they take a reading.

Drawing from years of UC pressure chamber research, the app then builds a report showing the level of tree stress and recommendations with the baseline and crop specific seasonal growth stages already factored in.

“You can see which ones are stressed, which ones are in the sweet spot and adjust your irrigation instantly,” Kaplan said. “It totally streamlines the process.”

The app is available through a subscription, which includes updates and training. It runs about $1 per acre. For more information on Pressure Bomb Express, visit pressurebombexpress.com.

For more information on using pressure chambers, also known as pressure bombs, download http://ucanr.edu/datastoreFiles/391-761.pdf.