Dealing with the increasing volume of almond production co-products and maximizing their value will play an important role in the economic stability of the almond industry.

A 2020 Almond Conference session highlighted challenges in dealing with almond hulls and shells as almond acreage increases across all growing regions in California. The edible kernels represent only a third of the biomass produced annually in the state’s almond orchards. Along with the kernels comes 4.3 billion pounds of hulls, 1.7 billion pounds of shell and two billion pounds of woody biomass.

“Our goal is to explore new ways to use all the co-products,” said session moderator Josette Lewis, Almond Board of California’s (ABC) Chief Scientific Officer.

Lewis, along with ABC’s Guangwei Huang, Associate Director of Food Research & Technology, David Pohl of Pohl and Holmes Inc. and Mayo Ryan of North State Hulling, discussed some of the challenges associated with the annual accumulation of almond co-products and opportunities for turning the co-products into revenue streams for growers.

Pohl said he has seen tremendous changes in the almond industry since he started hulling and shelling in the mid 80s, with prices paid by dairies for hulls being a primary change. Initial low prices climbed steadily as California dairy demand grew. Value for hulls as part of a dairy cow ration reached $130 to $150 per ton, only to fall in recent years as dairy production declined.

“Economics is driving biomass research, and finding more value in the co-products is critical to the success and sustainability of this industry,” Lewis said.

Diversified Uses

A more diversified market for almond hulls will lead to an increase in value, said Huang. While hulls have been valued as a feed supplement for dairy cows, research is also directed toward innovative feed products for poultry and fisheries. There is also potential for food applications, Huang said. Powdered drinks, antioxidants, dietary fibers and emulsifying agents are some of the potential products from hulls.

Feed uses can be expanded as studies have shown dairy ration can contain 12 pounds of hulls per day for cows. Laying hen diets can contain 15% hulls and broiler diets can have a 9% hull ration.

Research is underway at UC Davis to convert almond hulls into protein-rich animal feed supplements. Funded by Almond Board of California, the study evaluated the feasibility of converting hulls to protein-rich fungal biomass and the fermentation residue’s suitability as poultry feed supplements.

Shells have also been identified as a good source for bio-energy production due to their unique physical properties. The shells can be converted to advanced carbon for energy storage, water filtration, etc. Torrefaction, where biomass is heated to 200 to 300 degrees C under inert conditions, is an alternate use for almond shells. Huang said that torrefied almond shells could be used to enhance properties of plastics.

UC Davis research into biochar as a soil amendment continues. Results from trials show almond shell biochars may be an appropriate material for use as a soil amendment. Research at UC Santa Cruz shows that almond shells are a good soil amendment to reduce loss or leaching of nitrogen degraded from green waste of vegetable farming.

Improving Quality

These value-added potential uses for shells and hulls, Huang warned, will require quality improvement in the raw product. Changes in the processing will be required along with modifications to produce better co-products.

Low quality is a factor in reduced use of hulls as animal feed. To increase consumption of almond hulls, he said, consistency and removal of foreign materials is critical.

Pohl, who operates a Hughson-based hulling and shelling facility, said that loss of co-generation plants taking woody biomass from almond processing challenged the industry to look for other outlets and also led to improvements in harvesting where fewer sticks and rocks were incorporated in loads coming from orchards. Incoming loads are charged on weight, so growers have an incentive to send cleaner loads to the huller.

“Changes have been significant in load cleanliness,” Pohl said. Growers understand that marginal product going in means marginal product coming out.

Mayo Ryan, who operates North State Hulling in the Chico area, said the grower cooperative is shipping almond hulls to dairies in Idaho and needs to send clean product. One of the challenges in delivering cleaner loads is the significant biomass remaining in orchards from previous crops. Orchards planted on gravelly soils also add to foreign matter.

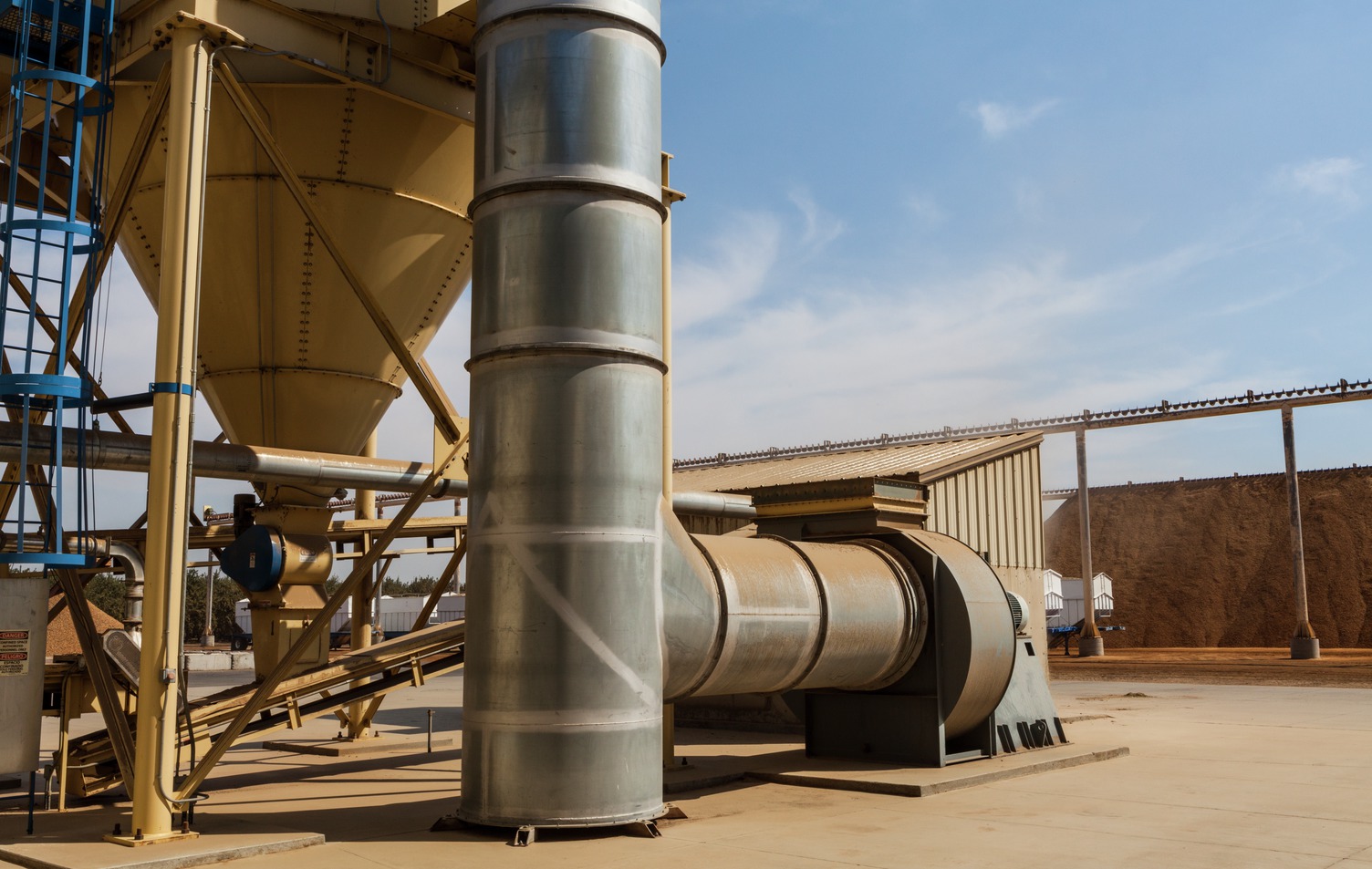

The plant installed a new hull clean-up line to send cleaner product to their dairy customers, Ryan said, and the investment is paying off.

North State Hulling, which has moved to a new site, is the only sheller with co-generation capacity, Ryan said. The process is emission neutral, and all types of biomass can be burned in the biochar retorts at the plant. Ryan said the plant also takes green waste as a feedstock. Next year, he said they expect the plant to be considered carbon neutral. Investments made in these processes are showing and return and payback is expected in four years.

“Biochar and composting operations at the plant are regenerative and have interesting environmental benefits,” Ryan said.

Lewis noted that the Almond Alliance is working on export markets for co-products. Reducing the bulk of the product by pelletizing hulls is one option being considered. Food safety concerns with co-products are unfounded, noted Huang. The products have less than 10% moisture and are stable. Aflatoxin is not an issue, he said.

Looking ahead, Pohl said the industry is looking at increased volume of co-products as well as much longer processing times.

“The 45-day run is a thing of the past. We’re now processing four to five months of the year up and down the state.”

With that volume and time frame, Ryan said, the industry needs to be creative and find ways to keep costs down and make money for growers.

Expanding the processing time frame, Lewis said, adds importance to stockpile management in order to deliver a quality product.