Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is all about utilizing pest monitoring and scouting information to make informed pest management decisions. Monitoring for insects and mites is a crucial part of the almond IPM. Although pest monitoring is a season-long process, springtime is the most critical time to strategize the monitoring tasks that last the entire season.

Pest Monitoring Basics

Navel orangeworm (NOW), codling moth and other insects’ trap counts are often tied with the degree-day models to make meaningful pest management decisions. Insect trapping provides a basis to determine the biofix date at which the degree-day calculation starts. In a general sense, biofix is the date when the targeted insect is captured consistently in the trap (i.e., beginning of the insect activities as the temperature warms up in the spring following the winter). Since insect development is highly temperature-dependent, heat unit accumulation (i.e., degree-days) is the better predictor of any particular insect life cycle event.

Degree-day models are available for major worm pests of the nut crops in California. The UC IPM website provides a platform for these models. Growers, PCAs and other professionals can access these models via ipm.ucanr.edu/WEATHER/ddretrievetext.html or by searching ‘UC IPM run degree-days.’ In this webpage, degree days models are available for several insects (NOW, codling moth, Oriental fruit moth, peach twig borer and more.)

You can see the pest (e.g., codling moth) and the model description (i.e., model type, lower/upper threshold temperatures) as well as a dropdown list to select the crop of your interest. On the next page, you have the options to choose the county (e.g., Stanislaus) where the orchard is located, biofix date (e.g., March 29) and end date (i.e., for determining the period that you are interested in running the model) and then hit the ‘continue’ button. Next, you can select your local weather station (examples: CIMIS #260, Modesto, or NCDC #6168, Newman, etc.) for the weather data.

You can also utilize the map link if you are unsure which station is best representative of your orchard location. Make sure that the up-to-date temperature data is available for the period of your interest. If you have access to weather data from other sources, you have an option to upload your data as well. Once you press the ‘calculate’ button, you can see the calculated degree days (daily and accumulated) for all dates from biofix to the end date entered. Contact your local UC Advisor if you have further questions on this.

The major pests that need attention in almonds include worm pests—NOW, peach twig borer, Oriental fruit moth; plant and stink bugs, ants, scale and spider mites.

Navel Orangeworm (NOW)

Removing the previous season’s unharvested ‘mummy nuts’ from the trees and crushing them using flail mowing or following other practices is critical to reducing the in-season NOW population. This process not only kills overwintering larvae but also takes out the ‘only’ resource for the first-generation egg-laying, thereby larval development. In almonds, the recommended mummy nut thresholds after the winter shake are <2 mummies/tree for the Sacramento and northern San Joaquin Valley, while 0.2 mummies per tree for the south San Joaquin Valley. This practice should be completed by mid-March altogether.

Trapping NOW

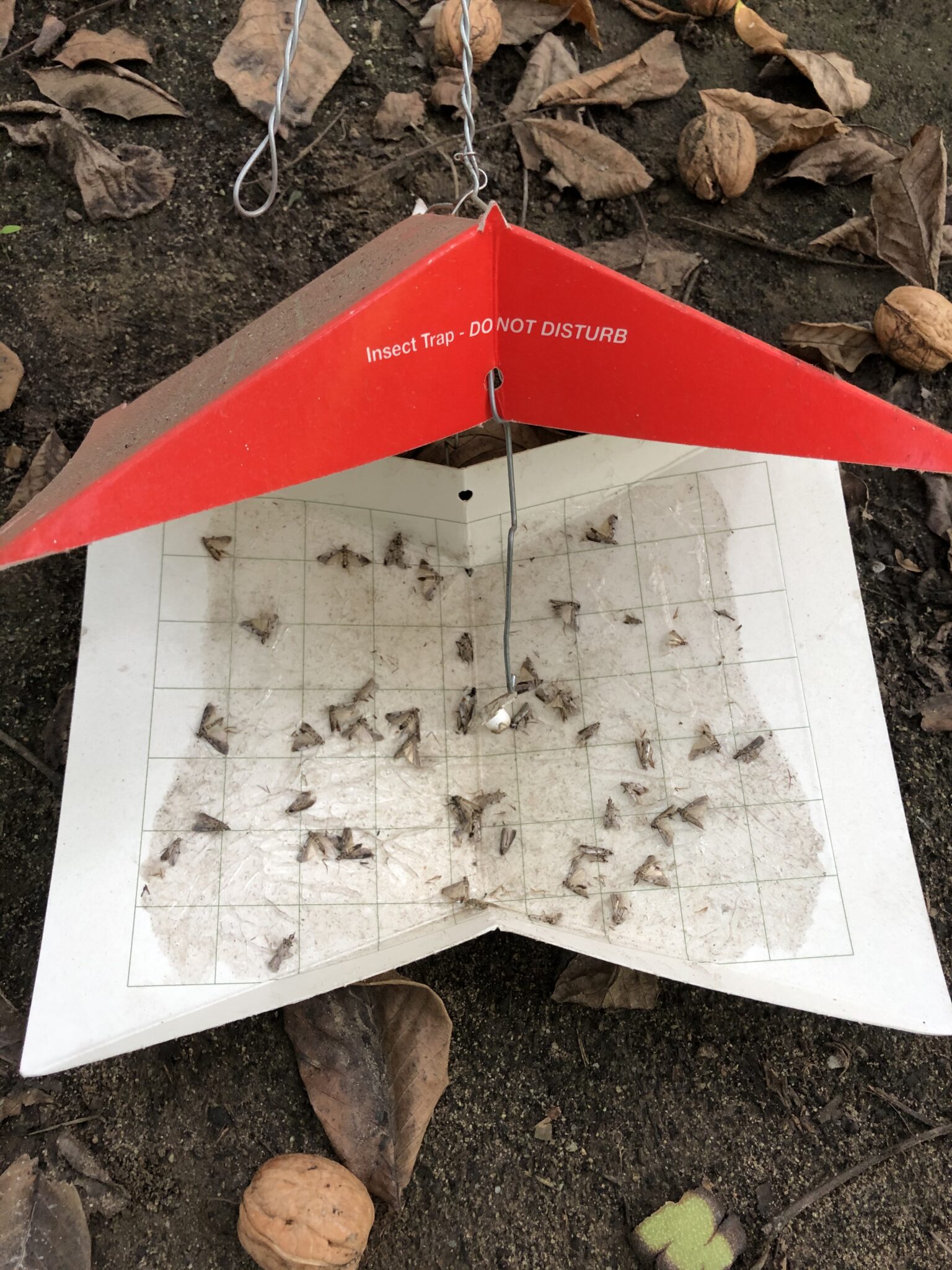

Timely utilization of available monitoring tools is essential for effective NOW management. Pheromone traps, which attracts male moths, can track the seasonal NOW activity in the nut orchards without NOW mating disruption pheromone. These traps should be placed in the almond orchard before April 1. In the orchard with NOW mating disruption, the pheromone trap, especially in borders and low-lying areas, is essential to assess whether the mating disruption is working uniformly within the orchard as complete trap shutdown is a positive indicator of the functional mating disruption.

Install the NOW egg traps out by March 15 (South San Joaquin Valley) or by April 1 (North San Joaquin and Sacramento Valleys) to set the biofix. Use black-cylindrical egg traps filled with the bait (e.g., almond meal + 10% crude almond oil). Some PCAs use other bait types as well, such as ground pistachio or almonds. Hang the traps on the north side of the tree, at least five trees in from the edge. Since the egg capture rate is highly variable among traps, the use of multiple traps (minimum four) is recommended and should increase as the block’s size increases. Set the biofix based on the egg trap. The biofix is the first of the two dates when egg counts for at least two consecutive sampling periods or when 50% or more of the traps have eggs. Check the traps one to two times per week, clean the trap surface after each inspection and replace the bait as needed.

The use of the ovipositional “ovibait” traps (e.g., Peterson traps) is the most efficient way to capture mated females in the orchard. Although this trap captures a substantially smaller number of moths than the pheromone trap, it is still a reliable trap due to its better association with the crop damage in almonds. Also, ovipositional baits performed better in the wing trap compared to the delta trap. Additionally, the ovibait traps can be used to track the seasonal NOW flight in mating disrupted orchards as the mating disruption pheromone shuts down pheromone traps.

Recently, a new type of lure, Phenyl Propionate (PPO), is commercially available for use in nut orchards and can be used in wing traps. Unlike ovibait traps, the PPO trap captures both male and female moths. Wing traps baited with the PPO + pheromone lure capture a statistically higher number of moths than the ovibait trap. Therefore, it provides a better resolution for monitoring NOW seasonal activities in mating disrupted orchards, especially under a low infestation scenario. The association between PPO or PPO+pheromone traps and nut damage has not been established, and future studies are needed to explore this relationship.

None of the trap types discussed earlier (i.e., pheromone, egg, ovibait, PPO) alone can provide complete information as their performance can vary substantially among orchards. Therefore, the combination of monitoring data from two or more trap types − and other crop-related information such as hullsplit status, variety, etc. − is essential to make an informed NOW management decision.

NOW Mating Disruption

Mating disruption products are available for NOW management in almonds. For NOW, two kinds (hand-applied MESO and aerosol dispensers) of the mating disruption products are commercially available from four companies. Some of these products are also available for organic orchard use. It is important to use these mating disruption products before the beginning of the expected overwintering flight in the spring, covering the entire season.

Essential considerations in applying NOW mating disruption in orchards:

Timing: Apply before the moth emergence time in the spring (before April 1, preferably.) Follow the product label.

Distribute the dispensers in a grid pattern, plus a few more in upwind edges to compensate for the wind’s influence.

Consider orchard size, wind direction, edge-effects, etc., while applying these products. Mating disruption is less effective in small-sized (<40 acres), irregular and narrow blocks compared to bigger, square blocks.

Select the limb closer to the center of the tree at the upper 1/3 of the tree height to hang the dispensers and apply in a way to avoid direct insecticide sprays on them.

Make sure dispenser nozzle is pointing away from foliage and limbs.

Make sure the dispenser units are working correctly before applying them to the field.

Peach Twig Borer (PTB) and Oriental Fruit Moth (OFM)

Pheromone traps should be placed in orchards in the spring (March 1 for PTB and February 15 for OFM) for monitoring them in almond orchards. These trap counts can be used along with the degree-days models (see description above on how to use degree-days) to predict the best timing for applying any pest control tactics. Besides, scouting the orchard for shoot strikes during the early part of the season (March to May) to detect and confirm the infestation by these pests is important to determine the need for treatments. Details can be found in the UC IPM Guidelines (Peach twig borer: www2.ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/almond/Peach-Twig-Borer/; Oriental fruit moth: www2.ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/almond/Oriental-Fruit-Moth/).

Leaffooted Plant Bug (LFB)

LFB feeding can cause significant crop loss in the spring if they are present in almond orchards. The LFB adults overwinter outside the orchard, but migrate to almonds during March to April and attack young nuts. Early infestation on nuts before the shell hardening causes nut abortion, while feeding after the shell hardening results in gummy or ‘brown spots’ kernels. Unfortunately, there are no traps and lures available commercially for LFB monitoring in the orchard. Therefore, regular orchard scouting and looking for live bugs, egg masses and damage indicators such as gumming nuts and dropped nuts are critical. Almond varieties such as Fritz, Sonora, Aldrich, Livingston, Monterey and Peerless are more susceptible to LFB damage.

Native Stink Bugs

Native stink bugs, (Green, Redshoulder, Consperse and Uhler stink bugs) which occur late in the season (June to September), can cause feeding damage, but they occur only late in the season (June to August). The infested nuts produce external gummings on the hull, and in many cases may not results in kernel damage, especially late in the season after the proper shell hardening. They don’t cause nut abortion as they are latecomers in the orchard. Don’t confuse the signs of true hemipteran bug (i.e., stink bugs and LFB) feeding damage (clear discharge from the nut) with the bacterial spot infection (amber color discharge). Sometimes, other physiological factors cause gummosis with clear discharge, but when you cut the nut, you should be able to see the sign of feeding mouthpart in the case of bug damage.

Invasive Stink Bug

Brown Marmorated Stink Bug (BMSB) is a new invasive stink bug in almond orchards in California, and is currently present in almond orchards in the central region of the Central Valley. BMSB feeding can begin as early as mid-March when they begin to migrate into the orchard from overwintering shelters (i.e., human-made structures such as buildings, barns, woodpiles, etc.) Over the past three years, our studies suggested that BMSB can damage all stages of almond fruits and is present in the orchard throughout the season. Although other true bug pests, such as leaffooted bugs and native stink bugs, may be present in almond orchards at times, the seasonal abundance of BMSB is often high, especially in other hosts nearby – the most common is the tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima). Also, BMSB infestation is much higher at the orchard edge than the interior.

Early season feeding by BMSB causes nut abortion, resulting in substantial nut drops. Mid-to-late season infestations produce clear gumming on the hull (similar to other stink bugs) and result in gummy, darken-spots or dimpled kernels. We also observed that some varieties are more susceptible to the damage than others. For example, Monterey and Fritz showed a higher level of damage than Padre and Wood colony varieties; Nonpareil is in between.

For BMSB monitoring, commercial traps and lures are available. We recommend using the sticky panel (9 x12-inch double-sided sticky trap) stapled to the top of the wooden stake (5 ft. tall) and installed on the ground (4 ft. tall.) The BSMB lure is then hung from the top a half-way of the sticky panel. These traps should be placed in a border-tree row facing open fields and other potential overwintering sites. We recommend conducting visual sampling of the orchard for stink bug life stages to confirm the infestation. The visual observation should also be focused on border trees. Other details here:

Ants

Ant colony survey begins in June in the upper San Joaquin Valley and in April to May in the lower San Joaquin Valley. Select five representative areas within the orchard (~1000 sq. ft. per location). Count the total number of ant colonies from the sampled area and estimate the potential nut damage at harvest. The longer the nuts remain on the ground after the harvest, the more damage you can expect. Ant monitoring details can be found here: ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/C003/almond-antcolony.pdf

San Jose Scale (SJS)

For SJS monitoring, put out pheromone traps by March 1. The use of double-sided sticky tapes can be used to monitor SJS crawler activities during the season. Details of SJS monitoring can be found here: ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/C003/m003bcsanjosescale.html.

Spider Mites

In almonds, start monitoring for spider mites biweekly from March to May, and weekly or shorter intervals after that. Early mite damage is indicated by the lightly stippled leaves (ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/T/I-AC-TSPP-CD.113.html) in the lower and interior portion of the tree canopy. Take a minimum of 75 leaves from five random trees and inspect the leaves for the presence of mites and mite predators using a hand lens, and determine the percent infestation. In addition to the leaf sampling, the use of multiple yellow sticky traps within the orchard is highly recommended to document predators’ seasonal activities such as six-spotted thrips, spider mite destroyer beetle, etc. Leaf sampling before July 1 should focus on ‘hot spots’ of the orchard (i.e., area near the dirt roads, stressed trees and field edges.) Follow the sampling guidelines for details: ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/C003/m003fcspdmites02.html.