When should growers start irrigating?

“Short answer: wait for the tree to tell you when it needs water,” according to Ken Shackel, professor of irrigation in the UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences. There’s also the questions of how much to irrigate and how to know that it’s working.

Measuring Stem Water Potential

One of the best ways to know when to irrigate in walnut orchards and other crops is to take a tree’s stem water potential (SWP) through the use of a pressure chamber, according to Kari Arnold, UCCE farm advisor in Stanislaus County.

In a 2021 Virtual Walnut Series presentation, Arnold said that pressure chambers measure tree stress through readings taken during the hot hours of the day. The values collected from the readings are then compared with baseline values that are specific to a given crop, which are dependent on temperature and relative humidity.

To use a pressure chamber, find the terminal leaflet of the inside branch closest to the tree root between 1 p.m. and 3 p.m., according to Arnold. Next, close off the selected leaf with a foil-formulate bag and leave it on for ten minutes. With the leaf still in the bag, place it inside the pressure chamber accordingly and start pumping the chamber to apply pressure to the leaf.

“What happens is that you start to get this bubbling [on the cut stem edge],” Arnold said. “That’s your point where you read the pressure on the leaflet.”

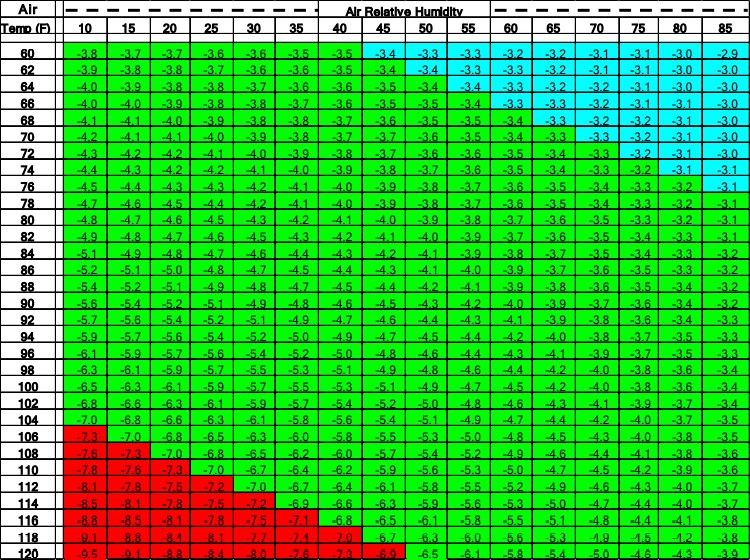

This pressure value shows how much water tension the leaf is experiencing. Once the value on the leaflet is read, it is compared with baseline numbers on a chart (contact your local farm advisor for a baseline chart specific to your crop.) A walnut chart, for example, contains a range of temperature (60 degrees F to 120 degrees F) and humidity (10% to 85%) values plotted against each other to give values of midday SWP measured in bars tension to expect for fully irrigated walnut trees (See Table 1).

“When we start irrigating, we want walnut trees to be between 1 and 2 bars below baseline,” Arnold said. “This is based on previous research that showed that walnut trees behave better and look better when below baseline, and yields are not affected.”

When to Irrigate and How Much

Calculating bars from baseline that the leaf is experiencing is simple, and the calculated value tells the grower when the tree is ready for water. First, take the value on the baseline chart for that day’s temperature and humidity and subtract it from the value on the pressure chamber gauge. If the resulting number is between 1 and 2 bars below baseline (negative number), it is time to “open the flood gates,” according to Arnold.

Determining how much water to apply to an orchard requires some different resources. Arnold noted that UCCE sends out weekly emails that provide evapotranspiration (ET) estimates calculated by the Department of Water Regulations using CIMIS weather station data. These estimates should be used only as a guide for how much water to put down at a given time, according to Arnold, and followed up with SWP measurements.

Follow-up SWP measurements will ensure the effectiveness of a given irrigation in the orchard. “You can take that funky contraption [pressure chamber] back out to the orchard, do the same measurement and see where it sits,” Arnold said.

If a measurement for a walnut tree reads 2 bars above baseline, for example, the trees are well irrigated and do not need to be measured again or irrigated for one to two weeks, according to Arnold. Arnold noted that growers do not need to regularly irrigate to two bars above baseline, however.

“Most times, trees rebound to baseline and don’t go much further,” she said. “UCCE advisors are happy to help further with questions and values.”

Soil Moisture Depletion

In a previous article from the October 2020 edition of West Coast Nut, Allan Fulton, UCCE farm advisor emeritus in Tehama County, said that pressure chambers aren’t a standalone solution for irrigation; rather, they complement other tools like soil moisture sensor readings as well as aforementioned ET estimates.

Soil sensors don’t provide the “when” and “how much” like pressure chambers and ET estimates do, but they do provide indications of where water is being taken up by the root system and where in the soil profile it is being depleted, which dictates the effectiveness of an irrigation set.

In a 2019 study done in a Central Valley walnut orchard, Arnold and other researchers placed a soil sensor at depths of 18 inches and 36 inches to measure where moisture was being depleted. Between March and December of that season, according to Arnold, they found that more moisture was depleted over time with each irrigation set at the 3-foot depth.

“A number of researchers have actually seen that walnuts do better in situations where moisture is being depleted at about three to four feet below the soil line,” Arnold said.

Pressure Chamber Adoption

Although use of pressure chambers has been proven through research to be a beneficial irrigation management practice, Shackel, who has been promoting the device for almost three decades, said in a previous West Coast Nut article that the industry has been slow to catch on.

“I’ve been saying, ‘This is a really good tool,’ but it’s really taken a lot of time to catch on,” he said. “The main resistance to it is people regard it as a scientific instrument and say it’s too detailed. There tends to be a little bit of bias against a monitoring tool that requires hand labor.”

According to the same article, a recent survey by the California Department of Food and Agriculture’s Fertilizer Research and Education Program noted about 16% pressure chamber use in perennial crops.