The health experts recommend 6 to 10 cups of water per day for the average human depending on your activity level. Wouldn’t it be great if you could get up in the morning, decide how much work you were going to do that day and, after careful calculations, suck down that much water at breakfast and be good for the day? It doesn’t work that way. We need water throughout the day.

Unfortunately, due to logistics and timeframes, that’s how we irrigate our crops. Load them up for a day or two and then let them fend for themselves for the rest of the week. Pulse irrigating can be much more beneficial. Full disclosure, its often much easier for me, with only 40 acres of pistachios on the farm on which I live, to run down the hill in shorts and flip flops and turn the pump on or off at any hour of the day or night. Most of my farmers can’t do that. So, how do we handle that?

Changing Our Practices

With bigger farms, the need for automation has never been greater. Our energy charges are astronomical, and they’re even worse between 5 p.m. and 8 p.m. due to peak rates. If we were to calculate those charges and be able to run 12-hour sets three to four days a week instead of 36 to 48 hours straight, we’d find that over the course of the summer, it would add up to thousands of dollars in savings. Clicking on a well at 8 p.m. and off at 8 a.m. will do that. Watering at night will also make your water go farther with less evaporation. As more and more restrictions squeeze profit margins in agriculture, we need to be cognizant of every penny we spend. The question arises as to what, if any, other benefits we would notice by changing our irrigation practices.

We know that our trees don’t eat their food, they drink it. Water solubilizes some nutrients, softens soils and brings much of the nutrition to the roots. So much of the microbiology in our soil depends on water to propagate and thrive. They transform many nutrients into forms a plant can use and symbiotically exchange their nutrition for root exudates. But they don’t do well underwater.

What we often overlook is that soils also need oxygen in pore spaces to function properly. When we run long sets with microirrigation systems or old-fashioned flood blocks like many of my walnut farmers, the soil stays anaerobic for way too long. Much of the good microbiology and even macrobiology get overrun by water and the bad guys. Typical anaerobic bacteria and fungi provide little to no nutritional value to the soil. They also give off ammonia gas and hydrogen sulfide, that rotten egg smell often found in swampy ground. Soggy roots don’t perform like well aerated feeder roots high up in the soil profile. Worms die, matter rots and bad players can take over. In soils that drain quickly, long irrigation sets push much of our soluble nutrition below the feeder root zone and render it ineffective. We paid for it and put it on, but our trees never had a chance to drink it.

Improving Quality and Yield

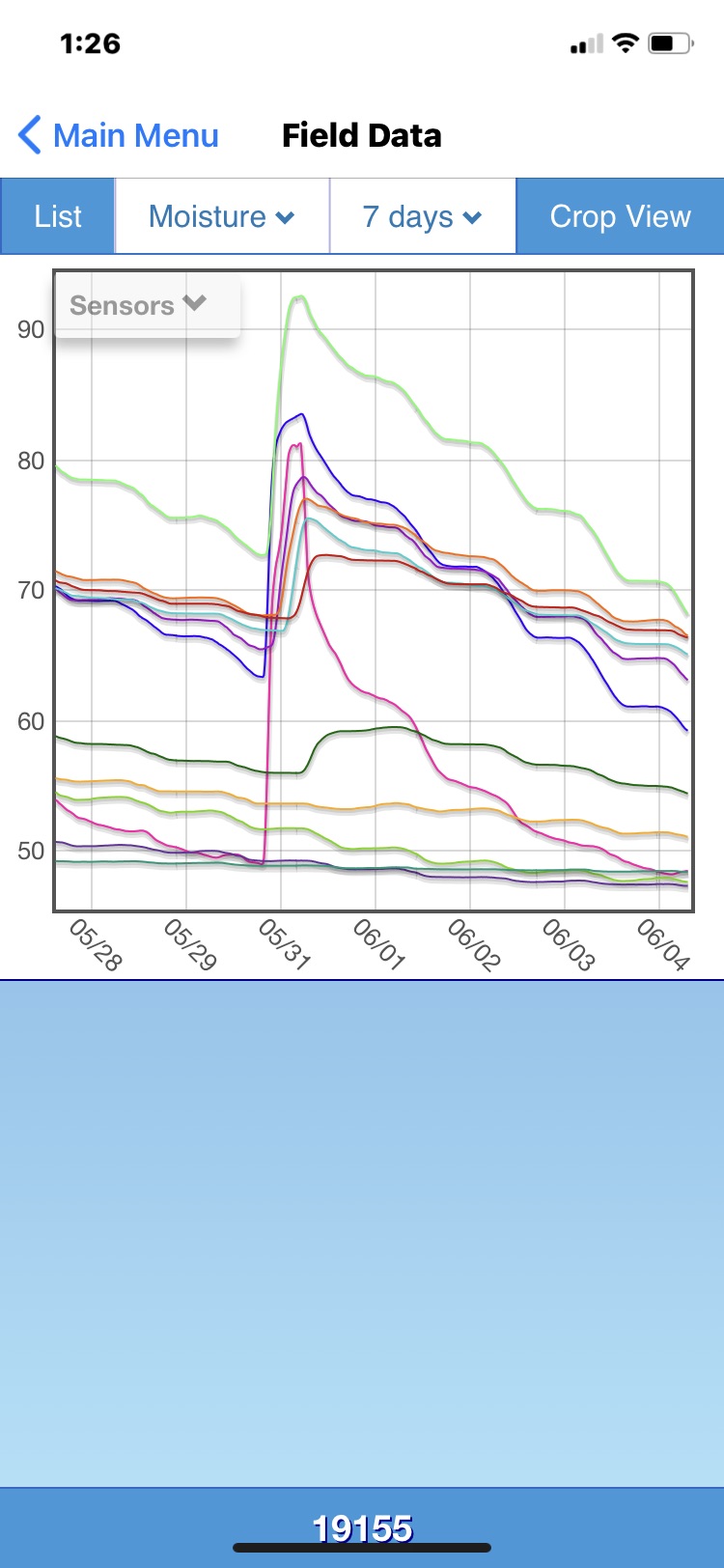

In California, more so than other states, we have to make every drop of water count. Growing a crop is not easy, and the last thing I want to do is put more on my clients’ plates. But what if there was a better way? How much better can our quality and yield improve with pulse shots on our irrigation and, more importantly, fertigation? Calculate how long our sets need to be to meet ET (only running specific hours doesn’t cut it if one system puts out 1000 gallons a minute while another well puts out 600gpm.) Run soil probes, a good old-fashioned soil auger, shovel or soil moisture meters. You want to know exactly how quickly your water gets from the surface to 12” where most of our feeder roots are. Fertigation for that amount of time and keeping more of your nutrition in the root zone before the next irrigation event will ensure more nutrition is picked up. Drying down a bit and opening pore space will allow more of our beneficial soil biology to transform more nutrition quickly and make sure it is absorbed. If you have to run longer irrigation sets, try to fertigate with smaller pulse shots in between.

Adding humates to your nutrition plan will also enhance soil health. Increasing organic matter by just 1% will allow an acre of soil to hold 20,000 more gallons of water. That can go a long way during a well issue or lengthy harvest period. The extra carbon will also chelate much of that nutrition that isn’t picked up quickly during the current fertigation event. It’ll help keep it from tying up with other ionic components as soils dry down a bit and keep it available for later use. The last thing we want is for a nutrient to lock itself back up into the original form we mined and attempted to solubilize in the first place to get it on our field. Humic and fulvic acids go a long way. Compost works well, but try to incorporate it and don’t let it degrade and volatilize in the soil surface. Even adding forms of sugar to nutrition can have benefits with the extra carbon.

Every time we are faced with the issues farmers realize on a daily basis, we have to be willing to make changes. Oftentimes, those voluntary changes can have dramatic effects on our bottom line. Water and power are two of those crucial elements that become significant. Better management of those two can have lasting effects on how our nutrition is assimilated as well. The money you can save can go into your nutrition budget or more automation. As new practices become more efficient and beneficial, that extra money you earned and saved will be well worth the effort.