Harvest is finished, and it’s tempting to sit back and rest from the work of the season. But as any good grower knows, the season these days never really ends. Postharvest is an important time for pruning, nutrition, protecting trees from freeze damage and a host of other things, according to Luke Milliron, UCCE orchard systems advisor for Butte, Tehama and Glenn counties.

Reducing Freeze Damage

A top postharvest priority should be preventing and reducing freeze damage, Milliron said.

The one thing growers should be most aware of for preventing freeze damage is, “Soil moisture, soil moisture, soil moisture,” Milliron stressed. “Maintaining that in fall and not being like, ‘I harvested, I irrigated once, I can just move on.’”

What used to be a concern for freeze damage in young trees is now for mature trees, too, Milliron said.

“I had a lot more calls on mature trees devastated than young trees, which is kind of a paradigm shift for the whole industry. The concern used to just be the young trees, but we’re seeing wood with a diameter of nine inches or more being killed back,” Milliron said.

Getting the trees into dormancy is crucial, Milliron continued. “You really do need several nights or mornings of those temperatures at or near freezing, and we just haven’t had that. We’ve gone from temperatures with daytime highs in the 70s and even into the low 80s, and then seven to 10 days later, we have lows of 26 degrees F, and the trees are completely unprepared to deal with that,” Milliron said.

Milliron has at least one grower in the Northern Sacramento Valley that has had the same orchard hit by freeze every year for the last three years, he said.

Part of the problem, Milliron said, is lack of rain until late fall these last few years. This makes it important to have surface soil moisture, and ideally, irrigating two to three days ahead of a freeze, he added.

Milliron spoke with a large grower in the Chico area who, for the most part, escaped any freeze damage this year, and he said that after experiencing freeze damage in 2018, he read the UC articles on the need for soil moisture. Now, he irrigates to some extent all winter, Milliron added.

“So, they’re not cutting off in the fall,” Milliron explained. “They’re doing some fall and early winter irrigation to keep some soil moisture and reduce the severity of the freeze damage,” he said, and it appears to be working.

Milliron suggests the following steps to prevent freeze damage:

If there has not been adequate rainfall by the end of October, irrigate young and mature orchards going into November. Compare rainfall totals with evapotranspiration (ET), and monitor soil moisture levels by hand or with sensors. Trees with adequate soil moisture appear to withstand low temperatures better than trees that are dry.

Actively monitor soil moisture and freeze predictions in November. If a freeze is predicted and the soil is dry, wet it two to three days prior to a freeze event. The top foot is the most important and should be at field capacity (not too wet); frozen water on the soil surface will make it colder because stored heat in the soil can’t be released back to the atmosphere.

If freeze damage is suspected in the fall or winter, check the tissue by cutting into it with a pocketknife and looking for drying or browning. Subsequent sunburn can further damage tissue, particularly on the southwest side of the tree. Paint the southwest side of damaged trees with 50% diluted (1:1 water to paint) white interior latex paint. Painting up to a week after the freeze event can decrease damage by half or more.

Pruning

Prune as early in the fall as possible to avoid Botryosphaeria (Bot) infections. Research has shown that winter pruning results in Bot infection in 78% to 99% of cut shoots, compared to fall pruning with 28% to 75% infection. At minimum, avoid pruning cuts when there are wet conditions in the forecast, Milliron stressed.

“We know that because of the large pith opening in walnut branches, they can remain susceptible to Botryosphaeria infections for a long, long time, maybe even three, four-plus months,” Milliron said.

“You do see higher infections if you wait until winter to prune,” he continued, and this is partly due to rain in the winter.

“But also, later pruning means that in the next four months, you are headed into warmer spring weather,” Milliron said, and winter pruning is problematic because there’s going to be rain in the next few months followed by warmer weather that is ideal for bringing on Bot infections.

That’s why Milliron is in favor of pre-harvest summer pruning or as-soon-as-possible postharvest pruning, especially since it can be difficult for growers with large acreage to finish pruning before winter.

Nutrition and Weeds

If leaf sample analysis indicates a potassium deficiency in the orchard, an application of potassium sulfate or potassium chloride (KCl) postharvest is advised. KCl can save money, but be sure the chloride can leach out of the root zone before spring leaf-out, and is therefore an unwise choice if we continue to have drought conditions.

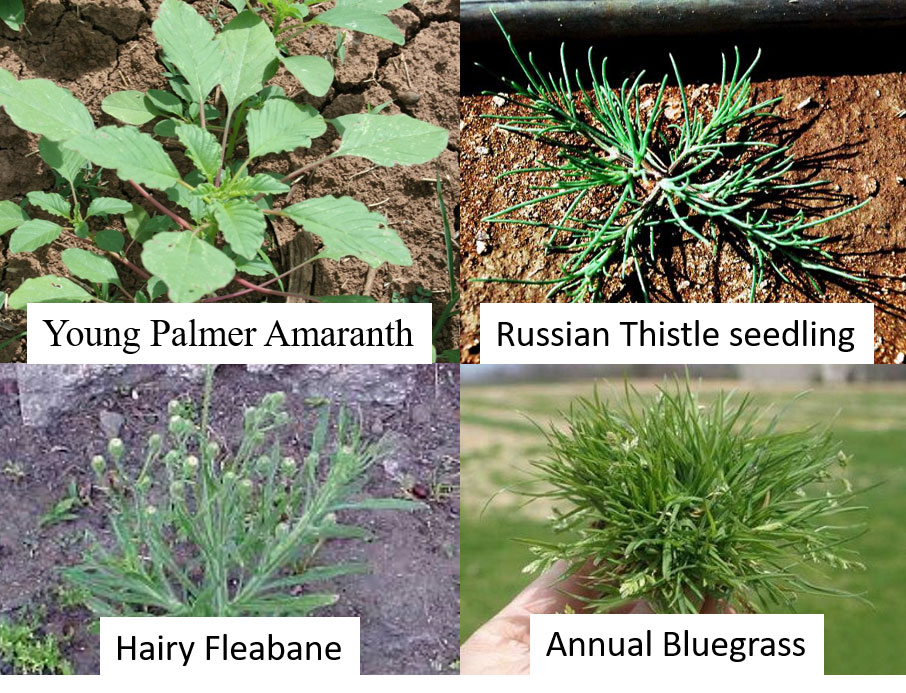

Postharvest is a good time to scout for weeds and evaluate your weed management plan, and if necessary, revise it for next year.

Milliron recommends downloading the weed scouting form from UC IPM and surveying the orchard to see what weeds are breaking through. It’s also important to keep track of those weeds and scout for weeds a couple of times a year to see which are problematic, he added.

“I think more and more people are going to be spotting the weeds that have one or multiple herbicide resistances,” Milliron said.

That’s why scouting pays, he continued, because seeing those weeds makes growers aware there is a problem and potentially do a spot spray or apply a different mode of action herbicide.

Not scouting for weeds could allow the weeds to gain a foothold, and then require an extensive cleanup program across the entire field, Milliron said, adding this makes scouting important. For more information on scouting weeds, visit growingthevalleypodcast.com/ipm-1/weedsurvey-p6ytl.

Sanitize Orchards

Orchard sanitation is a key management practice to combat navel orangeworm (NOW), and even with low prices for walnuts, sanitizing orchards is highly recommended.

Remove mummy nuts that can harbor overwintering NOW. Shake or pole any nuts left in the trees, blow nuts into the middles and flail mow. Don’t forget to clean out nuts from processing facilities that are close to orchards as well, Milliron said.

“We’ve been lucky with last couple years in walnuts. We’ve had pretty low navel orangeworm pressure across the state, but if that changes, and I think that will, that’s probably when people will be more inclined to take sanitation more seriously,” Milliron said, adding that it’s important to remove mummy nuts to prevent NOW from overwintering in them.

Harvest Samples

Walnut harvest sampling can uncover several common sources of kernel, shell and hull damage, including damage caused by insect pests, diseases and environmental/physiological factors.

Knowing the source of the damage will provide information about how successful the pest management program was during the season, i.e. how effective were: treatment decisions, timings, materials and applications.

This will also give insight into changes for the following season, and it’s important to keep block-specific historical records to help focus pest management activities in subsequent years, Milliron said.

With worm damage, note the size and stage of development when the initial infestation occurred to compare with monitoring and treatment records to improve future pest management decisions. Multiple years of sampling and site-specific historical records can help guide the harvest sampling process.

Milliron recommends collecting a representative sample of nuts from each block at harvest, and with two shakes, obtain a proportional sample from each shake. Collect nuts from different areas of the block. If the nuts are collected after they are blown into rows, be sure to collect throughout the pile as infested nuts may weigh less and be lower in the pile.

In a perfect world, samples should be processed soon after collecting. If they must be stored for any length of time, remove the hulls within a few days of collection and record any hull infestation or damage, then refrigerate the samples. This will limit rotting and movement of pests between nuts. Once hulls are removed, relatively dry nuts will hold for a period of time in cold storage (refrigerator temperature), but freezer temperatures are best for longer storage, Milliron said.