Depressed walnut prices and higher input costs have put a premium on pest management decisions and increased the importance of dormant monitoring for scale pests in walnuts.

UC IPM Pest Management Guidelines advise growers and crop consultants to monitor scaffolds, limbs, branches and prunings in the dormant period for San Jose scale, Italian pear scale and, most prominently, for walnut scale and frosted scale. At high populations, walnut and frosted scales can reduce yields and quality and create issues with other plant pests, particularly Botryosphaeria.

Both scales inflict damage by sucking plant juices from leaves and twigs and reducing growth and vigor. “This manner of feeding creates entry points for pathogens and UC Plant Pathology Specialist Dr. Themis Michailides has correlated scale infestation with increased incidence of Botryosphaeria infection in walnuts,” said Emily Symmes, Ph.D., former UCCE IPM advisor and current Senior Manager of Technical Field Services for Suterra.

Symptoms of trees infested with walnut scale include a water-stressed appearance and die back of fruiting wood on lateral bearing cultivars. High populations of frosted scale reduce terminal growth and vigor, resulting in smaller nuts and poor kernel quality. Additionally, the frosted scale can secrete large amounts of honeydew that covers nuts and contributes to growth of sooty mold, increasing chances of sunburn.

Research has shown that when monitoring for the pests, growers and PCAs should simultaneously look for biological control activity. “Evidence of parasitism is fairly easy to identify as small holes on the scale bodies where the adult parasitoid has exited its host,” Symmes said.

Guidelines call for examining a minimum of 100 branches and tree scaffolds from throughout an orchard, and to make observations at varying heights. “Getting up in the tree canopy on a pruning tower can be an excellent means of monitoring tree tops, which is important as infestation can vary at different heights in the tree canopy,” Symmes said.

Walnut Scale

According to UC Davis literature, the walnut scale is the most important armored scale pest of walnuts. It has two generations per year in the Central Valley, overwintering primarily in the second-instar stage. In spring, the scales resume development and adult males emerge as tiny winged insects, while females remain immobile under the scale cover. After mating, females lay eggs in May that will typically hatch in two to three days. Crawlers will disperse before settling down to feed and secrete the white scale cover. The cover color will change to gray in about a week.

The first generation typically completes development by mid-July. Second-generation eggs are laid around mid-August and the crawlers will again disperse before molting prior to overwintering.

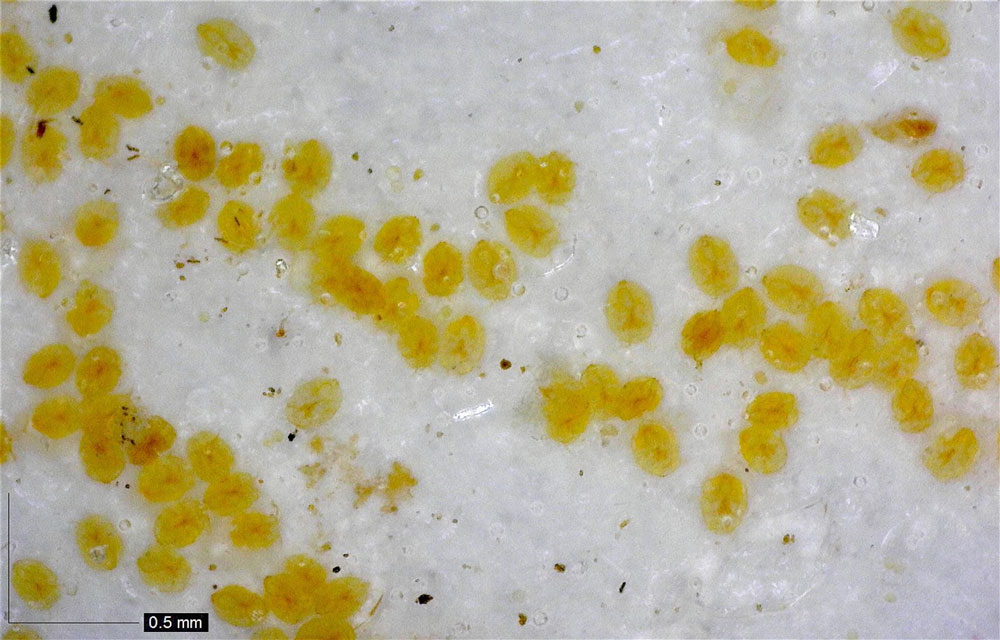

When looking for walnut scale in the dormant period, look for daisy-shaped groups of male crawlers under the margins of circular female covers. When lifting the scale cover, look for a yellowish body with indented margins. These features distinguish walnut scale from other armored scales on walnuts.

It is also important when scouting for walnut scale to confirm that the majority of the population is still active prior to making any treatment decisions, Symmes said. “The scale cover can stay attached to the plant tissue even when the insect beneath is no longer alive,” Symmes said.

She advised growers and PCAs to remove the scale cover with a small blade or a fingernail and examine the body beneath. “If it is bright yellow and ‘squishy,’ it is still alive,” she said. “Dead scales will be darker yellow to translucent and often slough off easily when removing the scale cover.”

Frosted Scale

Frosted scale, which is considered the most important soft scale pest of walnuts, has only one generation per year. It overwinters as a nymph on twigs and small branches. The nymphs, or crawlers, emerge from beneath scale covers from late May through June and settle mostly on the underside of leaves. From there they will feed during summer months. In the fall, nymphs molt and move back to twigs.

When monitoring for frosted scale during the dormant period, UC IPM guidelines call for examining the previous season’s growth on randomly selected trees throughout an orchard. Treatment threshold is reached if finding more than five nymphs per foot of last year’s wood if less than 90% of the nymphs are parasitized.

When looking for evidence of the parasites, look for nymphs that are almost black and have convex covers. Unparasitized nymphs, conversely, are flat and opaque. Several parasites commonly emerge from a single parasitized adult scale, leaving a perforated cover. Past research has shown that parasitoid populations can increase over time, and researchers recommend growers consider holding off on insecticide treatment as long as possible to allow for parasitoid populations to build. When insecticides are deemed necessary, Symmes advised growers to choose the most selective chemistries available to preserve the predator and parasitoid populations.

Also, consider orchard management history when gauging whether to treat. Low to moderate numbers of either walnut or frosted scales are not considered a significant threat to orchards, according to the IPM guidelines, particularly if biological control agents are present. Careful monitoring and knowing the history of pest pressure cycles in the orchard can help inform whether it is prudent to rely solely on natural enemies in a given year, Symmes said.

Delayed-Dormant Treatment

If treating for the pests, UC IPM Guidelines recommend doing so in the delayed-dormant period before shoot growth begins, especially if using an insect growth regulator. Further, the guidelines recommend placing double-sided sticky tape around limbs near adult scales in early spring to monitor for crawler emergence.

For walnut scale consider performing a follow-up treatment if finding yellow, mite-sized crawlers congregating on the edges of sticky tapes. For frosted scale, a follow-up treatment may be necessary if finding eggs under adult females on the sticky tape and crawlers actively moving beneath the scale. Eggs will be white and shiny in appearance, resembling tiny grains of rice.

Monitoring over several years has shown that crawler emergence is variable, coming as early as the third week of April and as late as the third week of May, so crawler treatment should not be timed by the calendar, according to Symmes.

Various insecticide options can be used to control scales, including buprofezin, pyriproxyfen, spirotetramat, bifenthrin/imidacloprid and acetamiprid, according to the UC IPM Guidelines. Among these, buprofezin and pyriproxyfen during the dormant or crawler periods are most effective and are selective choices that can help mitigate non-target impacts to natural enemies, according to Symmes.

Narrow range oils can suppress low to moderate numbers of walnut scale during summer months, but can be destructive to walnut aphid parasite. Guidelines advise growers to refrain from applying oils if trees are suffering from low soil moisture or other stress factors or if temperatures are expected to exceed 90 degrees F at the time of application.

For frosted scale, narrow range oil can be effective during the delayed dormant period, but should be applied only after buds begin to swell as a dilute application in at least 300 gallons per acre. As with the walnut scale, an application in summer will suppress low to moderate numbers.

Deciding whether to treat for scale pests can be a difficult decision, particularly when profit margins are low and biological control agents often keep the pests in check. But, at times, not treating can be more costly than spending money on an insecticide.

“Research has shown that a good insecticide application can provide suppression of walnut and frosted scale for multiple seasons, so annual treatments may not be needed in every orchard,” Symmes said.

Symmes added that through dormant monitoring, growers can get a good idea of whether they should treat for these pests or let biological control agents do their work for them.