Pistillate flower abscission (PFA), a production problem largely relegated to walnut varieties that make up only a small percentage of California walnut acreage, continues to pose risks for producers growing the varieties Serr and Tulare.

Certain environmental conditions favor the problem and there are some cultural steps growers can take to minimize the effects of PFA. Effectively treating for PFA generally involves deciding to spend hundreds of dollars per acre on a plant growth regulator, a decision made more difficult with low walnut prices.

The California walnut industry first encountered PFA after the release of the variety Serr in 1968. For many years, Serr was widely produced and it continues to be grown today, although only on about 10% of walnut acres.

“Serr was touted as an early variety that had high vigor, good shape and very high nut quality for its time,” said Bob Beede, a retired UCCE farm advisor who continues to consult for the tree nut industry. “Even to this day, it is a cultivar that has a good edible yield, has excellent flavor and is harvested on a timely basis.

“Then, in the early ‘80s, people started noticing problems with PFA, which they referred to as the ‘Serr drop problem.’ It occurred shortly after fruit-set when nutlets were falling in abundance on the ground,” he said.

At one point, several UC Davis researchers were studying PFA in walnuts in hopes of determining the cause of the Serr drop problem and potential solutions to it.

“A lot of people worked on it,” said Joe Grant, research director for the California Walnut Board and a retired UCCE nut crops advisor. “Early on, nobody knew what caused this. All kinds of things were tried and failed. Finally, Vito Polito, who was then a professor at UC Davis, figured out it was too much pollen.”

Polito, who has since retired, discovered that excessive pollen on the flowers was generating a high level of ethylene, a plant hormone associated with ripening of some fruit. “What was happening is the ethylene was causing a rapid aging of the flower… hence the flower dries up and falls off,” Beede said.

Growers tried a variety of practices to combat issues with PFA, including knocking off some of an orchard’s catkins and altering the amount of nitrogen they applied. But no silver bullet solution emerged and, eventually, as the Chandler variety grew in popularity and Serr acreage shrank, the issue was relegated to the back burner. In the early 2000s, however, PFA erupted in several Serr orchards, causing a reboot of research into control measures.

“We had two or three back-to-back Serr yields where the crop was only about 1,000 pounds an acre and the growers were in a panic,” Beede said.

At that point, acreage in Serr was dwindling, but its early harvest meant it was still an important variety for meeting the Thanksgiving and Christmas markets in Europe, Beede said. And he launched an investigation into the issue after several growers approached him. “I re-rung the bell about pistillate flower abscission,” Beede said.

At about that same time, Beede heard a report from Polito that in laboratory conditions, the growth regulator AVG, the active ingredient in ReTain, interfered with ethylene development and the rapid aging of flowers.

What happened next, Beede said, ranks as the most dramatic discovery he made in his 35 years as a farm advisor in terms of a yield increase.

Dramatic Discovery

“I went back to this grower who wanted me to work on this, Bill Verboon, and he had a Serr orchard that had only produced about 500 pounds the previous year and I went out with a squirt bottle one Saturday morning and treated 20 trees and five individual shoots and tagged them,” he said.

Beede came back three weeks later and was amazed at what he found: The treated shoots had set 98% of their flowers, whereas the untreated had set just 20%.

A recount led to the same figures, and over the next decade, Beede conducted 30 experiments on ReTain as well as other plant growth regulators.

“What we learned is AVG is a very powerful plant growth regulator when applied at the proper time,” he said. Beede documented yield increases as high as 1,500 pounds an acre in some cases when treating Serr walnuts with ReTain.

“We also found some improvement in Tulare orchards,” he said. “I did not study other varieties.”

Still, with the cost of ReTain running $300 an acre at that point and deciding whether to treat orchards with the growth regulator was not and still is not an easy decision, according to Beede.

“In order for AVG, or ReTain, to do a grower any good, they first have to have a significant pistillate flower abscission problem,” he said.

Asked how a grower can determine if he or she has a significant problem, Beede said the best way is to get up on a pruning tower, tag female flowers just prior to bloom and mark the shoots with flagging tape. “Spray them with ReTain and don’t spray others and see whether or not within three weeks you have a much better set on the treated shoots than you do on the untreated shoots.”

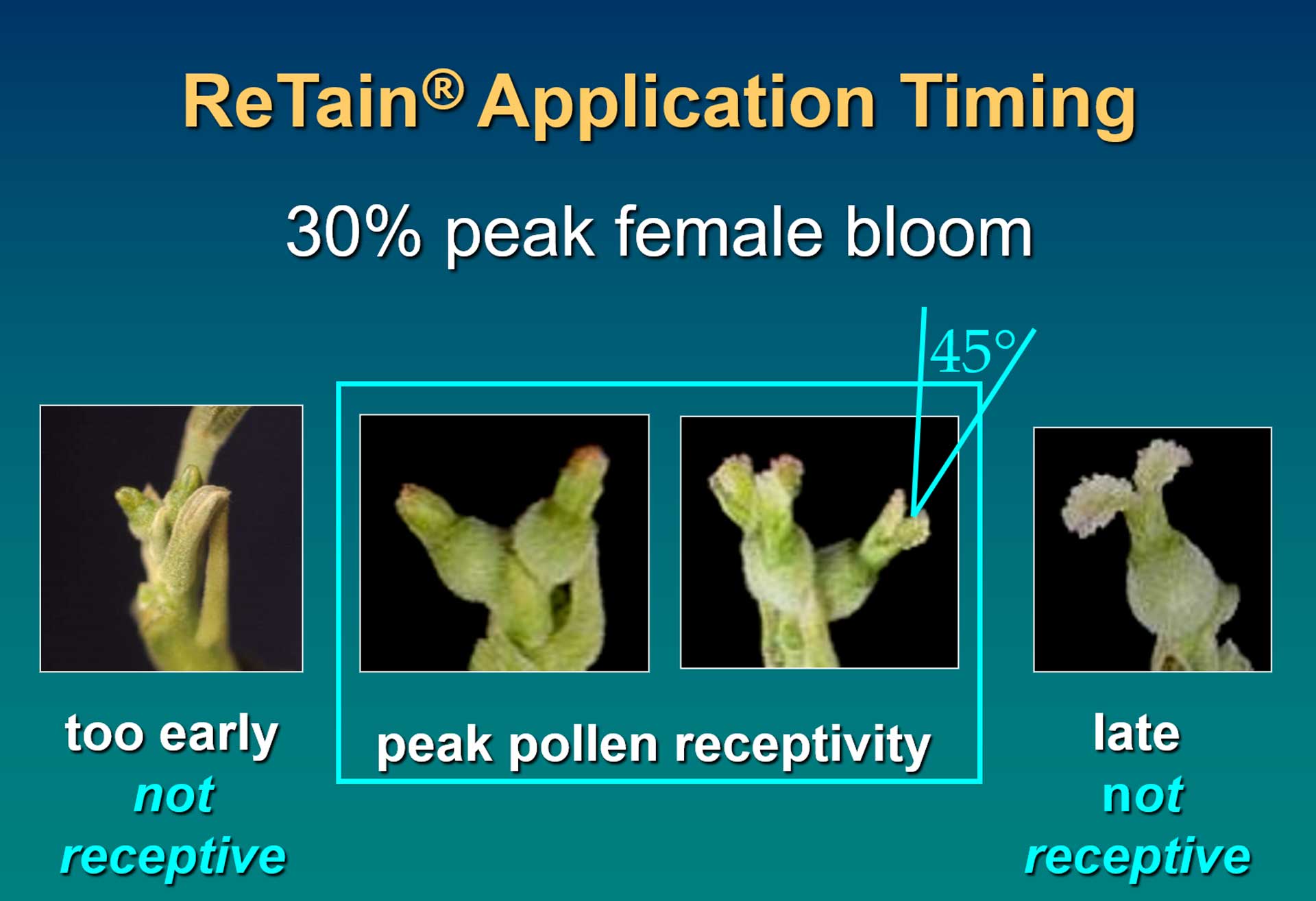

A second, less labor-intensive method involves buying a bag of ReTain, following label directions and spraying an acre or so of trees at between 30% and 40% bloom and compare that acre’s performance to others in an orchard, he said.

“Either go out and spray a row and sacrifice one season or get out there and tag flowers,” he said.

Historical Yields

Growers also can look to historical yields to determine if PFA is causing a problem, particularly in Tulare walnuts, where PFA incidence is less of an ongoing issue. “I always tell growers that if their Tulares are already yielding 5,000 to 6,000 pounds, then I would be reluctant to mess with success,” Beede said.

Another factor that can play into spray decisions is whether rainfall occurred during bloom. “We found that rain during bloom, if it was significant, say a quarter of an inch during peak catkin pollen release, diluted the pollen sufficiently that either the value of ReTain or catkin shaking was minimized,” Beede said.

Removing pollinizers from Serr and Tulare orchards can help, Grant said, but isn’t always sufficient to reduce pollen load given that release of pollen from adjacent orchards can still lead to significant pollen loads, regardless of whether a grower takes out pollinizers.

One thing that Grant advises against is to wait until symptoms develop. “You can’t look for symptoms,” Grant said. “You are looking for factors that contribute to it, and that is a lot of pollen or a lack of rainfall that would reduce pollination, and history.”

Application timing and rate are well known by this point, Grant adds. “The only question is are you going to get your money back or not.”

It’s a question that has persisted now for many years.