The Almond Board of California, in conjunction with Blue Diamond Growers, UCCE and Land IQ, has designed a voluntary online platform that helps connect neighboring growers and PCAs interested in or currently using NOW mating disruption. The platform is designed for almonds, pistachios and walnuts, all tree nuts that are susceptible to NOW damage. The goal is to help growers and PCAs create larger orchard blocks better suited to the mating disruption system, said Jesse Roseman, Almond Board principal analyst.

He emphasized the program is purely voluntary, but participation may help enhance the almond industry’s sustainability message.

“Can we create a voluntary system that shows growers are being proactive and that could help avoid worse negative burdens coming next?” Roseman said. “This voluntary approach may not only be preferable to something being forced on growers; it may also be more effective.”

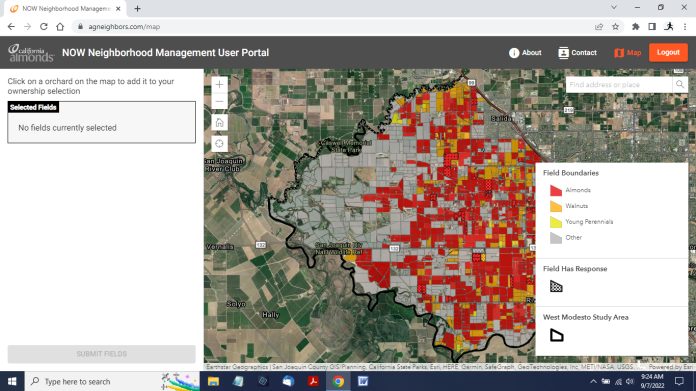

The Almond Board, which received project funding from the California Department of Pesticide Regulation, successfully piloted the online matchmaking system with growers and PCAs west of Modesto during the 2022 summer.

“We had a kick-off meeting and got around 30 growers and PCAs in that [west Modesto] area, so there’s definitely interest,” Roseman said. Blue Diamond helped spread the word about the pilot program since the co-op has an extensive communications network.

The Almond Board is rolling out the neighborhood program statewide for the 2023 season, he said. Growers of susceptible tree crops and PCAs active in Central Valley orchards are invited to use the tool. It can be found at agneighbors.com. The passcode is “nowmd”.

Being Neighborly

By creating a free online account and logging onto the website, users can view field boundaries and crop maps from Land IQ. By clicking on blocks they manage, website users then select whether they’re using mating disruption.

Once tool use closes, notifications will be sent to nearby growers and PCAs whose combined acreage meets the minimum 40-acre threshold. Making those connections and helping with follow-up should aid those who would like to take a neighborhood approach to using the pheromone-based system, Roseman said.

Although the Almond Board received the grant, the system is also for walnut and pistachio producers since those crops also are susceptible to NOW damage. And the pest can spread across different crops and fields.

As part of the statewide launch, Roseman said they plan to first raise awareness of mating disruption among growers of the three susceptible crops.

“I think a lot of growers, especially the larger growers, know about it, and many have tried it,” he said. “We know adoption isn’t as widespread among smaller growers, and it may not be something that works for everybody. But for the ones who are interested in it and the ones who want to partner with their neighbors, it creates a more effective treatment area.”

The cost to implement NOW mating disruption averaged $127 per acre in 2021, according to Almond Board figures. But growers increased their average crop value by $144 to $150 per acre that year.

Growers who want to try mating disruption also may be able to receive cost-share funding from the Natural Resources Conservation Service, NRCS, Roseman said. The Almond Board, along with UCCE, developed NOW standard practices on which NRCS based its funding.

Known as Conservation Practice 595, the combination of IPM and natural resource conservation program is designed to reduce pest pressure, injury to beneficials, pesticide transport to surface and groundwater, emissions of particulate matter and emissions of ozone precursors.

Eventually, Roseman said they hope the mating disruption program will become sustainable without outside financial support.

Taking to the Air

Mating disruption involves blanketing an area with synthetic female insect pheromones emitted from season-long dispensers, such as timed-release aerosol cans nicknamed “puffers” or rubber-like impregnated Meso strips hung from trees. Recently, a flowable microencapsulated pheromone spray has been launched for commercial use with NOW mating disruption, although the neighborhood project is based on UC research findings that used aerosol and Meso dispensers.

Inundated with pheromones, males become confused and frequently can’t find a female with which to mate. Eventually, the NOW population declines.

Many walnut, apple and pear growers have successfully adopted mating disruption for codling moth in blocks as small as 20 acres, although the system works better with larger contiguous orchards.

Because NOW moths are stronger flyers than codling moths, researchers have looked at minimum contiguous block sizes of at least 40 acres for NOW mating disruption. Of course, contiguous blocks larger than 40 acres work even better.

Mating Disruption Put to the Test

In trials conducted in the San Joaquin Valley in 2017 and 2018, UCCE Farm Advisors David Haviland and Jhalendra Rijal found a 46% to 50% reduction in NOW kernel damage with mating disruption. Haviland had three trials in Kern County while Rijal had three trials in the northern San Joaquin Valley.

Their research was the basis for the Almond Board’s program, said Rijal, area integrated pest management advisor for San Joaquin, Stanislaus and Merced counties and a project collaborator.

“We knew it worked in bigger plots,” he said. “We used 40 acres or more to do that research, but there are a lot of smaller growers. How can we communicate among the growers so they can form a voluntary group and create blocks where they can use mating disruption together?”

Mating disruption isn’t a stand-alone answer to NOW either, Rijal said. Instead, it is part of an integrated approach that also involves winter sanitation to reduce overwintering populations, in-season trapping and monitoring, timely harvest and properly timed pesticide applications at hull split.

Although mating disruption has performed well in trials and for some growers, Roseman said it also has limitations and should be approached accordingly.

“We’re not saying that use of mating disruption is going to automatically allow growers to save a spray, but that’s one of the potential benefits if you’re able to control NOW in your orchard.” he said.

This winter, Almond Board representatives and farm advisors will begin promoting the neighborhood program at grower meetings. Rijal said he discussed it as part of his presentation at the annual Blue Diamond Growers meeting and planned to continue at future meetings such as UCCE’s North San Joaquin Valley almond day.

In the coming months, Roseman said he also foresees grower field days to help get the word out.

“This is just the beginning of what we hope will take off, and it could help address some of the concerns we hear about the impacts of pesticide use,” he said. “If there’s a way we can reduce them and make pest management more sustainable by including cultural and pheromone-based control methods, that’s a goal as well.”

Vicky Boyd | Contributing Writer

A veteran agricultural journalist, Vicky Boyd has covered the industry in California, Florida, Texas, Colorado, the South and the Mid-South. Along the way, she has won several writing awards. Boyd attended Colorado State University, where she earned a technical journalism degree with minors in agriculture and natural resources. Boyd is known for taking complex technical or scientific material and translating it so readers can use it on their farms. Her favorite topics are entomology, weeds and new technology. When she’s not out “playing in the dirt,” as she calls agricultural reporting, Boyd enjoys running, hiking, knitting and sewing.