Sometimes your true calling shows up when you least expect it. Growing up in the snowy winters of Minnesota, it rarely occurred to Adam Orandi that California farming was in his future.

Orandi lived in the northern town of Fergus Falls, an area full of families who farmed various crops and livestock. His parents, however, were in medical professions. His mother was a nursing student, his father a pathologist who was the town’s coroner. But their family had a rich history of farming pistachios in Iran.

“I’m technically a sixth- or seventh-generation pistachio farmer,” Orandi said.

It wasn’t until he was a teenager that he started working the soil and learning pistachio tree nut farming and orchard management on the farm his father bought in Terra Bella, Calif. in 1971. Orandi’s summers were spent in the orchards, and he knew the nut industry was the place for him.

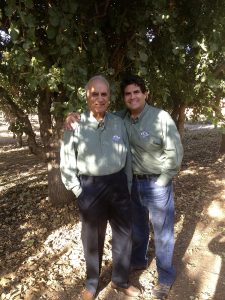

After years of learning the business firsthand from the ground up in this capacity, Orandi purchased and expanded his father’s original pistachio processing facility Orandi Ranch. Embarking on his solo venture, ARO Pistachios, today he oversees more than 1,000 acres of pistachio orchards across the San Joaquin Valley as CEO of ARO Pistachios and AOK Farming. The company is a family endeavor with his wife Pamela Orandi filling the role of communications and events, applying her background in publishing.

One of the things they appreciate most are the relationships they have made through Orandi’s service to the industry.

“That’s been another great part of being involved with this community. We’ve met so many fun, caring and really genuine people,” Pamela said.

Both she and her husband completed the LeadOn APG pistachio program early on, and she felt fully welcomed by generations of pistachio farmers.

Orandi served two terms on the board of directors for the American Pistachio Growers (APG) and as chair of the membership committee. Additionally, he served terms as vice president then president of the California Pistachio Export Council.

Whether he’s working in the orchard or serving on a committee, Orandi is cautiously optimistic about the future of the California pistachio industry and was happy to share his thoughts with West Coast Nut about both the past and future of the industry.

Q. Tell us a little bit about your family’s history with pistachios.

My dad, Mehdi Orandi, grew up on a pistachio farm in Rafsanjan, Iran, which is considered the pistachio capital of that country. He came to the U.S. in the 1950s to become a physician, and that’s how we ended up in Minnesota. He read that people were experimenting with pistachios in the U.S. in the late ‘60s and decided to drive out to California and look for himself.

In the early ‘70s, he planted his first 100-plus acres of trees before there was really a pistachio industry that we see today. I think the early pistachio commercial crop in the U.S. was ’76 or ’77, and so we were certainly part of the first development of California pistachios as an industry.

Q. How did you get involved in the industry?

I never knew I was going to become a farmer. I naturally thought I was going to be a doctor. But as life had it, I got into it, and I love it.

After college in 1993, I worked fulltime with my dad. He was my mentor and is very knowledgeable, and we spent a lot of time together side-by-side. On the farm, he had built a small pistachio processing facility, so I dove into that. That became more of my focus, the food manufacturing side.

I started my own company, ARO Pistachios, developing my father’s original processing facility and expanding it exponentially. In its first nine years, it increased from 1 million pounds volume to over 20 million pounds.

In 2020, out of the blue, I was approached to sell my facility. I loved what I was doing on the food-manufacturing side. But with expansion and managing something this size comes long hours. The buyer needed a home for his crop, my wife and I were raising our young sons, and I love being a dad, so we decided this was an opportunity. ARO Pistachios had several hundred employees at the time, and it was a very stressful job.

I decided I really would rather slow down. Another consideration was that I never could really get into the farming side of it as much as I’d liked because it was so expensive. The sale of the plant allowed me to invest in acreage. Now I’m fully on the farming side of it. I love it. It’s a lot less stressful. And it’s a legacy for my family.

Q. How have your farming practices evolved in recent years?

Water is imperative. We use technology to target the appropriate amount of water and make sure we are maximizing our yields using the correct amount of water, the correct amount of nutrition, the correct amount of pest control. The more precise we can be with that, the better off it is for everybody. The better off financially, the better off it is for the land, the safer it is for the consumer, the safer it is for the employees. We use instruments such as soil sensors that measure the water in the ground and monitor, verifying the appropriate amount of water is in there.

We use a lot of tech that is available to the industry. We use weather stations to track chilling hours, track temperatures, track all sorts of variables that go into our decision making for what, where, and when we apply farming practices.

Q. How do you feel about the future of the pistachio industry in California and the challenges it faces?

I am hopeful for all tree nuts in California: almonds, walnuts, pistachios. They all sail on the same ship with the challenges that they’re facing. They’re all very capital-intensive.

Some of the biggest challenges would be the regulation that’s coming in with food safety. It’s expensive and there are, of course, important considerations as with most industries. All of this regulation translates to more dollars for important areas such as food safety, air pollution, groundwater. All these things now add layers to the whole program, which directly and indirectly correlate to greater expense.

Land is not cheap in California. Water is a very serious issue whether you have groundwater or surface water. Then with your water portfolio, how are you addressing SGMA (Sustainable Groundwater Management Act)? 2040 is ground zero. You better have it figured out ASAP. Unfortunately, there are some growers who have not modernized their farming practices and are now faced with the burden of additional expenses. Sadly, a lot of farmers are in that boat where they don’t really understand and are getting some large invoices.

Q. What is your approach to SGMA?

I have a dozen or so farms, different locations, and each farm has groundwater, which is made up of your native yield and all the different factors that go into what you’re allowed to take out of the ground in that location. Then most of my orchards also have surface water, some sort of contract with the district, and it really kind of boils down to an account. In each account, you have this much water each year, you use this much water this year. What are you left with?

Now, that’s become a full-time job for my company, really managing the water demand for each orchard, making sure that we have a plan for each property. Reputable, knowledgeable consultants are a resource to advise on water board meetings, and together we collectively strategize. This is what every farmer in California is going to have to do. It’s not coming. It’s here right now.

I think there’s going to be some settling in the next few years. It’s been a very successful industry and people have been successful turning a profit, which has attracted a lot of attention, but SGMA really changed all that.

Q. What are the biggest assets of the pistachio industry?

In the U.S., one of the things we hang our hat on is food safety. We sell most of our crop overseas, and everyone is concerned with food safety, some more than others, but I think that gives us a competitive advantage in all markets.

Of course, with regulation comes cost, as I mentioned. On the global stage, people look for California pistachios because they know they can count on a certain amount of testing and protocol and production. That’s a big advantage for us.

Q. What are your thoughts on marketing pistachios?

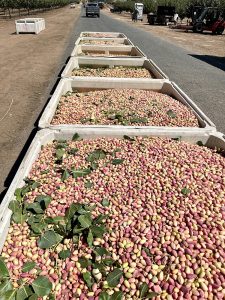

Pistachios take six to eight years to come into production. There are still a lot of trees in the ground that have been planted in the last eight years that are coming up. This translates to a huge increase in supply, which means we must be very strong in our marketing.

What I don’t want to see is commodity based. We want to get the most return to the growers because it’s super costly to get into pistachios and to farm it year after year without a penny back. You’re going deep into the red before you start to turn that around.

It’s vital to make sure we are marketing, that we are getting pistachios to people who have not yet eaten a pistachio. Pistachio nuts are a complete protein and such a beneficial food. We really need to focus on a combined effort as an industry to market our crop.

Q. How do you give back to the community, both in ag and in the community where you’re based?

Giving back to the community, I think, as a farmer begins with land stewardship. We need to make sure we’re not exploiting the ground and that we’re farming in the best, most responsible manner, not only for the soil, but for the area around us.

I believe in giving back and paying a fair wage. Helping in the community with youth groups, for example.

Q. What advice would you give to a young person getting into farming today?

The saying is true: if you love it, it won’t feel like work. There is a ton of opportunity for young people today to get into either the farming side of it or the farm-related industry. It’s a lifestyle. And if you want it, put in the effort, you will love it.