Diseases in nut crops can be affected by both cooler and warmer weather and intense weather changes can propel infections. Preparing for variations in weather patterns before a disease occurs might be helpful in preventing a problem, but there are also a number of established methods to controlling diseases brought on by wet weather once they occur.

UC Davis plant pathologist at the Kearney Ag Research and Extension Center, Themis Michailides, presented findings from research done on diseases in walnuts and pistachios during a presentation at the 2023 Crop Consultant Conference in Visalia, Calif. in September. He shared a history of the most likely diseases to occur in wet weather and tips on how to manage them.

Michailides focused on Botryosphaeria panicle and shoot blight, which first decimated pistachio crops in California’s San Joaquin Valley in 1998 and 1999, and can also cause major problems in almonds and walnuts.

According to information published by UCCE, Botryosphaeria fungi can cause many symptoms, but typically produce cankers on woody plants. These pathogens cause disease by growing around, along, or through the stem until the plant is girdled, killing the tissue. It usually kills the bark and cambium but can also enter the wood. However, the blight phase of the disease is the most destructive in pistachio and walnut.

Botryosphaeria’s Destructive History

Going back 44 years in his research, Michailides studied the total rainfall in California from 1979 to 2023, highlighting the years that had the largest increases in rainfall. One of those seasons, 1982 to 1983, saw nearly 14 inches more rainfall than average, which led into the first year that California saw Botryosphaeria panicle and shoot blight in pistachios, which results in blight of the panicle clusters and shoots of pistachios.

“That doesn’t mean the Botryosphaeria was not there, but that wet year was the year it became obvious and very destructive,” Michailides said.

By 1985, the first publication of the disease was printed in the UCCE journal California Agriculture. At that time, California’s 45,000 acres of pistachios had just one species of Botryosphaeria to contend with. However, today, there are eight more species causing this disease and there are now more than 453,000 acres of bearing pistachios in the state.

The next most damaging wet season for the disease came in the 1997 to 1998 season, when nearly 20 inches of additional rainfall drove a surge of the disease, spurring a major epidemic in California by 1999. Michailides said growers during that time didn’t have any control over the disease, and trees were damaged so badly, growers had no choice but to remove them, while those who chose to keep their trees, faced an uncertain dilemma of what would become of their orchards.

He went on to explain that normal rainfall conditions that take place when the disease occurs can be very misleading to growers, because symptoms don’t appear on the fruit, even though an infection has occurred. This is known as latent infection. If a spring occurs when rain is above normal, he noted that severe infections will occur even in green fruit, known as quiescent infections.

“These infections will develop as the fruit matures later in the season, end of July, August, and so forth. So, all the green parts of the pistachio can be infected, and all these parts can remain on the tree,” Michailides said.

In these cases, he explained, infections from clusters will lead to cankers that will remain on the shoots, while infected shoots remain on the tree, even rachises of clusters and infected buds, and each of those will then have the inoculum of the pathogen, pycnidia, where spores develop.

“So, when you have rains, these spores will spread around, but year after year, we’ll have an accumulation of these inocula on the trees,” he said, of the spores in the pycnidia, also called conidia. “Conidia are water-splashed spores; they will spread and cause new infections.”

He added that ascospores aren’t found in pistachios, but will enter a pistachio orchard arriving from walnuts, almonds, and riparian trees and bushes where Botryosphaeria fungi are plentiful.

A Cool, Wet 2023

Following Hurricane Hilary in August 2023, excessive rains caused severe outbreaks of another disease in pistachios, Alternaria late blight, according to Michailides. Typically, the Alternaria develops so late on the leaves of the pistachios that by the time harvest comes around, the fruit is clean, but that wasn’t the case this year, he said.

“This year, we saw it not only on the leaves, but also we saw Alternaria developing and causing mold on the nuts,” he said.

In previous research, he said it was recommended to not spray after July; however, these types of rain events could lead to additional research in order to revise previous information to see if later sprays will have an effect in reducing Alternaria developing on fruit.

Severe cases of Botryosphaeria were also seen in Tulare County orchards where growers didn’t spray in the spring due to long drought, he said.

“Botryosphaeria usually doesn’t show in drought years, but if inoculum were present in the orchard and you didn’t spray with this type of rain late in the season, you would see very severe Botryosphaeria on clusters causing major damage for the growers,” Michailides said.

Another disease that thrives in cool and wet weather and affects both male and female pistachio trees, is Botrytis blossom and shoot blight.

“Botrytis on pistachio develops only when you have wet and cool weather during bloom time, it kills the developing shoot and it kills the developing clusters,” Michailides said.

Botrytis symptoms, which start at the base of the shoot, typically become obvious by summer, causing the tender shoots to whither and bend like a shepherd’s hook, and also developing lesions and cankers. But Botrytis can be easy to control if there is a prediction of rain and the temperatures are predicted to be cool, he explained.

“One or two sprays in the spring will control the Botrytis,” he said, plus these sprays will also protect green parts of the tree from Botryosphaeria infections.

Walnuts can be affected by Botryosphaeria canker blight in wet years also, and was found in some valley orchards this past fall.

“Initially we found the disease in orchards where sprinkler irrigation occurs,” he said. “It can blight fruit and shoots without infecting the leaves directly.”

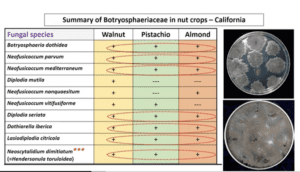

11 different species cause Botryosphaeria canker and blight of walnuts in California, Michailides said, while almonds and pistachios are each affected by eight species. Comparing the three, he said there are seven species that move from one nut crop to another.

“And we do know that these fungi are widespread throughout the walnut industry or also throughout the pistachio industry,” he said.

The way the disease presents itself in walnuts is similar to the way it presents in pistachios, he explained.

“There are latent infections that we don’t see any symptoms,” he said. “The fruit looks clean with no symptoms and that may confuse the growers.”

He noted that those infections begin to express disease around August or September as fruit matures. The infection will decay one fruit, and will move to the next, until eventually the infection will move into the spur, killing buds for the next year’s crop.

“And that’s why this disease is very destructive, very yield reducing, because it not only blights fruit during the season, but also kills the buds for the next season,” Michailides said.

Infected spurs remaining on the trees create yet another problem, because blighted shoots and spurs and even branches will sometimes have large amounts of pycnidia full of conidia (spores) of the fungus, which will spread once the rains come.

How to Manage

The best control measures for these diseases come down to cultural and chemical controls, says Michailides, with irrigation management, sanitation, and chemical application being the most effective.

Referring to an orchard that had a severe infection of Botryosphaeria, he said that making a simple adjustment to sprinkler head angles alleviated much of the problem.

“We noticed that the trajectory angle of sprinklers was 23 degrees, and we changed to sprinklers with 12 degrees and were able to get a 75% reduction of the disease by just doing that cultural control of irrigation management,” he said.

Other cultural control methods include pruning dead branches or blighted shoots to reduce inoculum in the orchard, as well as avoiding sprinkler irrigation that wets the canopy.

Chemical control of these diseases is very important because the chemicals available now are very effective, Michailides said.

Spraying is done to prevent infections in the spring, he explained. In pistachio in a wet year sprays start in April and end at the end of July in an approximately 20 to 30 day interval. If a grower chooses to apply only one spray, the critical (optimal) timing is the first part of June. For walnuts, calendar sprays are done in mid-May, mid-June, and mid-July. If the grower decides for one spray only, the best time is the second part of June to early July.

“So, a combination of pruning and controlling the scale and the fungicide applications in the spring will manage the disease,” he said, “but a fungicide program should be definitely implemented in rainy years, and some growers forget that.”

In general, Michailides said, watch for rain events; if there is high probabily of rain, spray before the rain. In this way, you get the best protection of your trees from Botryosphaeria diseases.

For more information on efficacy of fungicides for controlling Botryosphaeria canker and blight of walnut, Michailides directs growers and PCAs to the UCANR website: https://ipm.ucanr.edu/legacy_assets/pdf/pmg/fungicideefficacytiming.pdf

Kristin Platts | Digital Content Editor and Social Correspondence

Kristin Platts is a multimedia journalist and digital content writer with a B.A. in Creative Media from California State University, Stanislaus. She produces stories on California agriculture through video, podcasts, and digital articles, and provides in-depth reporting on tree nuts, pest management, and crop production for West Coast Nut magazine. Based in Modesto, California, Kristin is passionate about sharing field-driven insights and connecting growers with trusted information.