When Rosie Burroughs was diagnosed with stage 4 cancer a few years ago, she approached the treatment of her body like she does the soil on her farm: tackling it alternatively. For Burroughs, who is now cancer-free, every decision she and her family make on their farm is in the goal of soil health. The family has farmed in California for more than 130 years. Today, they grow an ever-evolving mix of regenerative organic tree nuts and livestock in Merced County and hold their practices to an unrelenting objective of improving the health of their land.

As growers explore systemic ways to grow food and fiber, the regenerative agriculture movement is continuing to create a buzz. But there’s also some confusion around the term “regenerative agriculture” and what it means, exactly. The topic was on the agenda at both the Almond Conference (TAC) in December and JCS Marketing’s Inputs Ag Summit in January. Both occasions allowed growers and industry experts to participate in conversations that rooted out the meaning of regenerative.

“For me, regeneration means working with practices that improve living ecosystems by restoring water, carbon and nutrient density cycles, which is enhancing the soil health with biodiversity and nutrient density,” Burroughs said during a panel she spoke on about regenerative agriculture at the Inputs Ag Summit.

She maintains soil, just like the human gut, requires the right biome and an ability for it all to work together.

“For us, all life starts in the soil, from the microbes in the soil to the birds in the air, all life depends on water and all these nutrient cycles that are part of regenerative practices,” Burroughs said.

Farming regeneratively can look a little different to each grower, but it often includes a combination of practices like little to no-tilling, cover cropping, and crop diversity, whether through the planting of multiple crops in one system or by utilizing livestock for weed and pest control.

For Justin Wylie, who spoke on the same panel, regenerative means not only helping the soil, but helping his bottom line.

“For me, it’s improving biology, improving soil health,” he said. “At the end of the day, what we’re looking to do is reduce inputs, reduce costs.”

Wylie co-operates Wylie Farms, a ranch management and consulting company. They also farm about 4,000 acres between Chowchilla and Madera, Calif., 600 acres of which is regenerative pistachio and citrus.

Wylie said if you look at the history of the last decade and a half or so, growers have had to think in new ways as markets change. And while pistachios are seeing huge price drops, he said he’s looking at a final price comparative to what his dad received in 1992, while modern-day inputs have only continued to skyrocket.

“In a lot of cases when there are drops in production or pricing, we make up for that with new varieties, by ripping something out and planting something new, higher densities, we’re looking at trellis now with crops we’ve never even considered it in,” Wylie said.

When speaking to his own clients about regenerative and where to save on the ever-increasing costs of inputs, Wylie said the focus is on survival.

“It’s mainly about how do we keep this thing profitable? And what I’m seeing on my pistachio budgets is our conventional budgets are $3,400 an acre in Madera with water, and our organic regenerative budgets are $2,700 an acre, and that is without any organic premium for now,” he said.

The Science Behind It

A panel at TAC addressed regenerative agriculture alongside the topics of climate smart and organic. Amélie Gaudin, associate professor and endowed chair in agroecology at UC Davis, said while each are different subjects, they share a lot of common ground.

She said the three concepts aim to manage for sustainability and look beyond productivity and yield.

“Regenerative systems apply an ecosystems approach to reaching management and conservation goals” Gaudin said. “There is flexibility in implementation, no single recipe, it’s context specific, and there’s a high likelihood of tradeoffs between functions. There’s frequent and multiple tradeoffs to manage in agriculture, so that’s something to keep at the forefront.”

How regenerative differs from climate smart and some organic systems hinges on redesign of the orchard and a stacking of practices, Gaudin said.

“Regenerative systems are ecologically complex, with low to no synthetic input and rely on farmers’ knowledge and experience to be successful,” she said. “It has livestock integration at the center of the framework and an emphasis on equity that climate smart frameworks don’t necessarily have.”

Having worked on organic and regenerative systems for the last two decades, she said while she’s happy people are having conversations about regenerative now, she also cautions to be careful not to wash down the definition of regenerative agriculture, or worse, to greenwash it.

Describing various levels of regenerative, Gaudin said entry level would be an orchard that is designed primarily to build soil health and sequester carbon, while a deeper regenerative system is also going to optimize biodiversity and conservation. At its deepest level, it will include an equity lens that supports individuals and community while striving for equity and reversing decades of extractions.

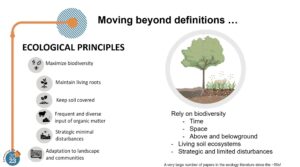

But she believes the industry also needs to move beyond definitions in order to make progress.

“My role is to provide data and bring this back to our scientific understanding of potential and processes to inform management. Whether you’re talking about organic, regenerative or climate smart, those systems must foster and rely on biodiversity to be effective” Gaudin said.

That biodiversity must be thought about in time and space, she explained, considering aboveground and belowground organisms in the living soil ecosystem.

“There is a very large number of papers in ecology literature since the ‘50s that have shown biodiversity sustain high functioning and productive ecosystems,” she said.

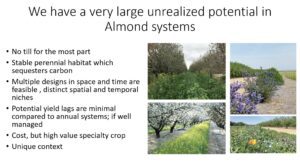

She said this is where a crop like almonds can win.

“We don’t till the soil so much; there’s a rainfed winter dormancy period when alleyways can be diversified, and there’s a lot of ways we can implement some of the principles,” she said.

In order to move beyond the definition, Gaudin said it will be necessary to ground an approach to principles rather than practices, since practices look different in different parts of the state.

“Eventually, you want to apply some principles that are core to ecosystem functioning,” she said.

Principles include maximizing biodiversity, maintaining living roots, keeping the soil covered, frequent and diverse input of organic matter, minimal chemical and physical disturbances, and adaptation to landscape and communities, she explained.

“Can we grow a high-biomass cover crop everywhere? Maybe not. Can these systems be considered regenerative? Maybe, if you can implement those principles in a way adapted to your context,” she said.

These systems already exist across California, she added, and have existed for quite some time, with growers implementing innovative practices through things like whole orchard recycling, organic amendments and compost, understory covers, cheap mulches and hulls and shells.

“We have a large menu of practices that can be implemented in various ways according to your operation, and soil type and water availability, for instance. Landscape features can also be considered; challenges and outcome of the practices will likely vary if your orchard is surrounded by almond, versus surrounded by a natural area or a more diverse crop mix.”

It can be easier to implement regenerative practices in high-value specialty perennial systems than in annual systems, Gaudin noted, so she sees a large unrealized potential in almond systems, which are already mostly no-till, consist of stable, carbon sequestering habitat, and where minimal potential yield lags have been observed.

“We’ve got a unique context in which we can make a difference at a large scale,” she said.

Kristin Platts | Digital Content Editor and Social Correspondence

Kristin Platts is a multimedia journalist and digital content writer with a B.A. in Creative Media from California State University, Stanislaus. She produces stories on California agriculture through video, podcasts, and digital articles, and provides in-depth reporting on tree nuts, pest management, and crop production for West Coast Nut magazine. Based in Modesto, California, Kristin is passionate about sharing field-driven insights and connecting growers with trusted information.