As the almond industry continues to learn from a season of destruction by navel orangeworm (NOW), UC researchers and industry experts agree planning for NOW throughout the year should be looked at as an investment, not an expense. A session on preparing for NOW year-round at The Almond Conference (TAC) in December painted a clearer picture of what happened in 2023, what IPM programs should look like to prevent a repeat and how to deal with affected product as it moves through the export process.

A year ago, growers, who were grappling with a low-price forecast, were looking for ways to cut spending, according to Kern County UCCE Farm Advisor David Haviland, who said many growers chose to cut back on sanitation, some couldn’t sanitize due to rain and others saw mating disruption as too costly. He added spray timings and programs were also out of whack, and obtaining a timely harvest was virtually impossible.

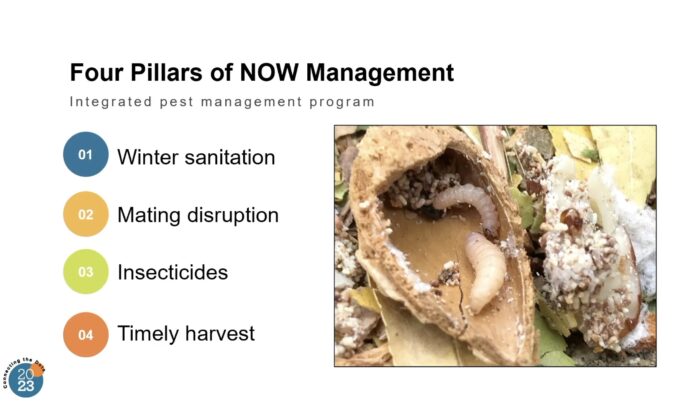

Addressing what happened with NOW, Haviland said growers need to consider what’s referred to as the four pillars of an NOW IPM program going forward: winter sanitation, mating disruption, insecticides and a timely harvest.

Breaking Down the Four Pillars

Haviland describes four important steps to sanitation: shaking, poling, blowing and mowing. With mummy removal playing an intricate role in NOW control, mummy reduction will reduce worms, make it more difficult for them to find mates, take away places for them to lay their eggs and physically exhaust the moths that do manage to get that far.

“The farther you go in reducing the number of mummies, the more impactful sanitation is,” he said. “That’s why we drive mummies and sanitation down to two per tree, so we’re impacting all of these reasons that NOW gets lower.”

With mating disruption, Haviland said it’s a predictable, effective and affordable method to controlling NOW. With the breakeven point at 1%, it’s the cost factor of mating disruption that should get growers thinking harder about using it.

“If you did not use mating disruption this year and you had more than 1% damage, you would have more money in your pocket right now if you had invested in mating disruption than by not investing,” he said. “When you look at it as an investment and what you’re getting back from it, that’s where it makes sense to use it.”

Haviland pointed out the typical USDA damage cost of 4% from NOW for weight not paid is just the tip of the iceberg and doesn’t take into account another 4% left in the field and 12 cents on $1.60 loss in bonuses, for a 16% economic loss overall.

“That’s why the economics of investing in navel orangeworm are so huge because these losses are much bigger than what shows up just on that USDA sheet,” he said.

As for insecticide use in 2023, growers were faced with a non-synchronized split that came in mid-July and didn’t coincide with the start of the second flight, and hull spilt sprays, if made at all, were turned upside down.

“That was a real struggle by growers, trying to navigate the best timing with everything out of whack,” Haviland said.

Discussing timely harvest as the fourth pillar, he said his definition of a timely harvest is harvesting Nonpareils before the third flight starts because most of the worms during the month of July are in the Nonpareils.

“If you’re able to shake your Nonpareils and get them piled and fumigated before any of those worms become adults, there’s no influence of the third flight on the Nonpareils, and you’re essentially removing the third flight from the field before it becomes the third flight,” he said.

Driving home the importance of a timely harvest, he added if 99% of Nonpareils get fumigated in time, there will be 99% control of the worms. Those that don’t get fumigated in time will emerge to become the third flight, leading to pinhole damage and eggs laid in pollinizers, which can then lead to an even greater fourth flight.

“Hopefully thinking about how to integrate those four pillars is going to get us back on track to where we were in the long term,” Haviland said.

Neighbors Matter

Referring to the “neighborhood” effect, Mel Machado, director of grower relations at Blue Diamond, said an unprecedented number of abandoned and unharvested orchards last year significantly affected the NOW population.

“How do you abate this? Because these things pumped out the moths,” he said. “You add that to the neighbor who cut some corners when you did it all, and you got mugged. How do you fight against this?”

Machado says some key measures to deal with the issue have to include reducing the inoculum in order to reduce the number of moths. This can be done with sanitation, eliminating “abandoned” orchards and mating disruption, he said.

Blue Diamond has created a tool to try and address that last element with the Neighborhood Mating Disruption program agneighbors.com, an online tracker that allows growers to say they’re participating in mating disruption or that they are interested in participating.

“You’ll be notified when we put together enough continuous acres that will be viable for disruption that you and your neighbors are interested in playing with each other; go forth and disrupt.”

He said NRCS funds are available to help growers with additional costs associated with mating disruption and their goal is to make this spread even to smaller blocks.

Aflatoxin Postharvest

Another issue that comes with orchards invaded by NOW is the risk of aflatoxin creating molds, which winter sanitation can go a long way to help control. Tim Birmingham, director of quality assurance and industry services at Almond Board of California, said NOW moths can carry these molds to nuts, which larvae then feed on, creating a microclimate that allows the mold to grow and produce the aflatoxin.

Aflatoxin in various crops is widely regulated around the world, with different limits in different markets, Birmingham explained. The U.S. regulates at 20 PPB, while the E.U. and Japan, two of California’s major markets, have much stricter limits. One of the biggest challenges with aflatoxin, he noted, is once it gets into the product, it’s not homogeneous, so it’s not uniformly mixed in the lot.

“You can have literally hot pockets, that needle in the haystack, that makes detection really difficult,” Birmingham said.

Demonstrating the correlation between insect damage and aflatoxin, Birmingham noted a study that looked at 50 different lots that showed insect damage constituted 7.2% of the weight from all 50 lots and amounted to 76.3% of the aflatoxin mass.

“This is telling us the majority of the aflatoxin we find is indeed going to be found in those insect-damaged nuts,” he said.

While the majority of aflatoxin shows up in insect-damaged nuts, smaller amounts can also show up as a result of other defects, like mold or chip-and-scratch mechanical damage.

“Once you disrupt the surface of the nut, you can create different little microclimates, which can allow the mold to grow or potentially the cross contamination with the aflatoxin,” he said.

Birmingham said handlers can mitigate the issue during sorting, citing a study that used a laser sorter followed by hand sorting to remove seriously damaged product.

“We know this is very effective,” he said. “We see lots that are failed for aflatoxin at higher levels, you can run them through this sort or sorting (we call it reconditioning), pull out the damage, and that will indeed lower the level of aflatoxin in the finished product stream.”

Since aflatoxin is typically non-homogenous, the size of a sample and how it is drawn will impact variability, and big samples are critical when testing. Birmingham said handlers have the chance to participate in the Pre-Export Check (PEC) program, which takes place on consignments shipped to the EU, which will test lots at a reduced frequency that have already been tested in the U.S.

“The handlers spend a lot of time, effort and money sampling that product, and they pull a very large sample to try to make sure they find that hot pocket, so that they can hold that lot back here before they actually ship it,” he said.

He noted while PEC specifies the EU will test at a reduced frequency, they do still test, and failed lots will still occur. In some cases, Birmingham said, higher-than-acceptable lots will still be sent to a foreign country. This is especially true in Japan since they test every consignment that comes in.

“This is a little bit of a challenge for the industry,” he said. “We are working with Japan to see if they will back off of that 100% testing requirement, but it’s a slow-moving process.”

Handers that do find failed lots needing to be returned to the U.S. should focus on getting them back as soon as possible, prepare and submit a reconditioning plan if required by the FDA and then reconditioning, Birmingham added.

Kristin Platts | Digital Content Editor and Social Correspondence

Kristin Platts is a multimedia journalist and digital content writer with a B.A. in Creative Media from California State University, Stanislaus. She produces stories on California agriculture through video, podcasts, and digital articles, and provides in-depth reporting on tree nuts, pest management, and crop production for West Coast Nut magazine. Based in Modesto, California, Kristin is passionate about sharing field-driven insights and connecting growers with trusted information.