Aluminum phosphide, or phosphine gas, has some new considerations for use by private applicators in California that may make rodent management more complicated in tree nut orchards. New requirements for licensing began January 2024 that require all existing private applicator certificate (PAC) holders to retake and pass a revised exam.

During a talk on the subject at a recent almond day hosted by the Madera County Farm Bureau, Madera County Deputy Ag Commissioner Bill Griffin explained some of the new changes and why it’s important the fumigant has such strict safety measures.

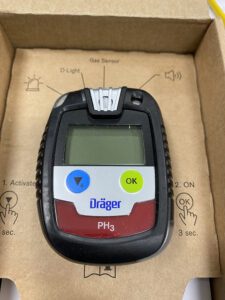

Aluminum phosphide is most used in a solid form of pellets and tablets, but also comes in a pure gas form, 100% phosphine gas, or 2% phosphine gas/CO2, he explained. As a fumigant for rodent and pest control, Griffin said phosphine gas interferes with enzymes and protein synthesis which affects the heart and lungs. But its effectiveness on pests means it can also be extremely hazardous to people as an inhalation and cardio hazard if not applied with all safety measures in place.

“The good part of it is that’s how it kills the pests, but the bad part is it can also kill you, so we want to take precaution to make sure that doesn’t happen,” Griffin said.

A Highly Effective Tool for Vertebrate Control

The damage vertebrates like ground squirrels, gophers and voles can inflict on orchards and other crops can be significant. A 2014 survey conducted by Roger Baldwin, professor of Cooperative Extension at UC Davis, asked growers about crop yield losses associated with a variety of vertebrate species. The survey asked growers about damage caused by bird and rodent pests to just 22 commodities across 10 California counties and indicated a loss of $168 to $505 million annually. The study acknowledged while wildlife provides many intrinsic values and ecological functions, controlling wildlife damage is clearly warranted in many situations to reduce deleterious human-wildlife interactions, it said.

Baldwin said pests like ground squirrels do obvious direct damage by feeding on nut and fruit crops, but they also tend to chew on irrigation lines, which can be quite costly for growers.

“The impact is the repair costs associated with that, which can be substantial. Also, it’s obviously going to alter distribution of irrigation water a little bit, too,” he said.

Nuts can also fall into burrow systems and be lost that way, and in general, the impact of burrow systems can damage farm equipment, cause increased soil erosion and pose a hazard to farmworkers.

Like ground squirrels, gophers can also cause major problems for trees, but their damage might look a little different. While gopher burrow systems can also be an issue, it’s the gophers’ tendency to feed on the root systems of trees that causes the most damage, especially in younger trees. They feed on the bark and the cambium layer, which leads to girdling of trees below the ground.

“When they girdle, that usually means they’re going all the way around the trunk, and when they do that, it completely cuts the flow of water and nutrients up to the rest of the tree, leading to the mortality of that tree,” Baldwin said.

Voles are another vertebrate that growers may come across, and while they don’t tend to cause the same number of issues that ground squirrels and gophers do, they can be especially troublesome if their population surges in an area, Baldwin said, adding that like gophers, they can cause extensive damage from girdling.

“The growers have to pay more attention to young orchards, particularly when it comes to gopher and vole damage,” he said.

He said trunk protectors, hard plastic tubes that wrap around the base of the trunk, will reduce girdling damage from voles. But he stresses that they must be buried underground about 6 inches, or they might create a hiding place for the rodents to do even further damage to trees.

When it comes to controlling vertebrate pests, Baldwin said aluminum phosphide is a very efficacious tool for both ground squirrels and gophers, but not something generally used for voles since vole burrow systems tend to be too numerous and shallow, causing gas to dissipate too fast to be effective.

He stresses soil moisture as the key to aluminum phosphide’s success, not so much the timing of application.

“You need to utilize it when you have sufficient soil moisture, that’s usually in winter to springtime, unless you’re dealing with a heavily irrigated crop, in which case, you can use it later in the year,” he said. “For the most part, you’re utilizing it in the winter for gophers, and the springtime for both gophers and ground squirrels.”

For ground squirrels, it needs to be used when they’re active aboveground, since they plug themselves up in their nesting chambers during hibernation and the gas won’t be able to reach them.

The treatment has close to 100% efficacy for ground squirrel burrow systems and 90% to 100% efficacy for gophers, Baldwin said.

While aluminum phosphide is one of the most effective tools to combat vertebrate pests, he said it’s just one part of a good rodent control plan. Baldwin stressed the importance of IPM and other available tools like baits, rodenticides, trapping, habitat modification, barn owl boxes for natural predation of voles and gophers, and certain cultural practice methods.

“Fumigation is one of those tools, so let’s utilize it when it’s applicable and switch to other strategies the rest of the year,” he said.

Cover crops can also be welcoming environments for rodents. Vegetation especially high in nitrogen like legumes and clovers will attract voles, which are cover-dependent, as well as gophers, so Baldwin recommended keeping growth mowed down periodically.

“Obviously, cover crops are beneficial in some ways for tree growth, but they’re also really preferred food resources for a lot of the rodent species, so you can see potential increases in populations of gophers and voles,” he said. “That’s just something that people have to keep in mind and consider.”

What’s Changed for Applicators?

Aluminum phosphide is a California restricted material that requires a permit prior to purchase and application, and the restricted material permit requires a certified applicator to supervise the use of restricted materials.

Griffin said there are new certified applicator licensing options for agricultural use, such as a Private Applicator Certificate (PAC) with a Burrowing Vertebrate Fumigation (BVF) qualification for property operators and their employees on property they own and/or operate. While he said PAC used to allow applicators to do fumigation with nothing additional, there is now a new exam which all private applicators must retake when theirs expire.

“Going forward, if you expire, you have to reexam; there won’t be any more CEs for the old PAC card,” he said.

If you have a current PAC and have taken the test already, your CE will qualify you as will a Qualified Applicator Certificate (QAL) or Qualified Applicator License (QAC), he said. But he added PAC card holders who haven’t taken the new exam will need to take it.

“If you want to use phosphine, any of the fumigants for rodent control specifically, you have to take the additional BVF exam,” he said, noting after that, there will be no need to reexam and six hours of CE units will suffice.

He went on to explain Property Management/Farm Labor Contractors (FLC) do not qualify for the PAC and must get a QAL or QAC if they want to use restricted materials at all. Property Management/Pest Control Businesses/FLC also must get a QAC or QAL with a category M to perform fumigation activities with any fumigant that is not a soil fumigant. Burrow and den fumigations are not considered soil fumigations.

Griffin noted a change to another category that many applicators have as well, category A, which doesn’t allow commodity fumes anymore.

“DPR modified category A, you no longer use category A for commodity fumes or postharvest fumigations; you have to get a category M,” he said.

While it’s a brand-new category, applicators won’t be required to retake the QAL/QAC license; you just need to add that category.

Changes to non-ag options include commodity fumigation at any location. Previously, PAC could fumigate at the site of production. As of Jan. 1, 2024, a regulation change removed fumigation activities from PAC with the exemption of burrowing rodents with the BVF qualification.

“But you have to take the new PAC and then take the burrowing rodent qualification, you don’t have to take any additional CE; you just have to maintain the CE you’re doing once you’ve done that part,” Griffin said.

He added all non-soil, non-ag fumigation activities require a QAC or QAL with the category M certification, and soil fumigation requires Category L.

He also reminded applicators that when using California restricted materials, they require the use of a notice of intent and use reporting. For ag use, site-specific reporting is due 24 hours prior to application. 24 hours is also required for non-ag use; however, a monthly NOI is due for multiple applications at various times. Griffin suggests working with your local county ag commissioner to create a notification system that works for you both.

For use reporting, ag use can be reported by site or in a monthly summary. While non-ag will most commonly report by monthly summary with all use reports are due by the 10th of the following month following the month of use, he said.

Kristin Platts | Digital Content Editor and Social Correspondence

Kristin Platts is a multimedia journalist and digital content writer with a B.A. in Creative Media from California State University, Stanislaus. She produces stories on California agriculture through video, podcasts, and digital articles, and provides in-depth reporting on tree nuts, pest management, and crop production for West Coast Nut magazine. Based in Modesto, California, Kristin is passionate about sharing field-driven insights and connecting growers with trusted information.