In 1980, when Carl Fanucchi helped plant the first pistachio orchard near Buttonwillow, Calif., he had no idea a major agricultural sector was about to be born.

What Fanucchi did know was that he was helping grower John Romanini find an alternative to cotton, which had long dominated farm country in the southern San Joaquin Valley. A few experimental blocks of pistachio trees had been planted farther north in the valley. But there was no proven formula for commercially growing the strange new tree in California. Even so, both Fanucchi and Romanini thought pistachios were worth a try.

Now, more than 40 years later, Fanucchi marvels at what followed that first pistachio venture. Driven by rising prices, pistachio plantings took off in California, crossing the 100,000-acre mark in 2001 and 200,000 acres in 2009. This year, pistachio trees cover an estimated 490,000 bearing acres in the Golden State, with another 40,000 acres expected to come into production by 2026. California now produces annual pistachio crops of 1 billion pounds or more, and pistachios rank among the state’s top 10 agricultural commodities.

Fanucchi, president of Fanucchi Diversified Management, has gone on to help develop more than 50,000 acres of pistachios for other growers. Kern County, where he and Romanini planted those first 5 acres, follows only Fresno County in California’s pistachio production. And Romanini’s original trees are still producing, averaging a hefty 4,000 pounds an acre at harvest.

“Five hundred acres of cotton never made more money than 20 acres of pistachios,” said Romanini, recalling the years when prices for the green nut were still profitable.

The Good Times Stall

But the good times have stalled for most California pistachio growers. Like many other agricultural commodities, the pistachio sector has come face to face with the downside of massive and rapid growth, volatile market dynamics and California’s production challenges.

Among the challenges growers are battling are:

The uncertain water situation and declining land values

Concerns about restricted water availability, coupled with mounting economic losses in pistachios, almond and walnut production, have upended tree nut land values. “It’s all about water,” especially in Kern, Tulare and Kings counties, Michael Ming told an audience at the agribusiness conference of the California chapter of the American Society of Farm Managers and Rural Appraisers, or ASFMRA, in Bakersfield in March. Ming is an accredited rural appraiser, professional real estate broker and owner of Alliance Ag Services.

As many as 900,000 acres of California farmland south of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta are likely to come out of production by 2040. That’s due to water pumping restrictions under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, or SGMA. The fallowing will include a combined 575,000 to 600,000 acres in Kern, Tulare and Kings counties.

“Those are staggering numbers,” Ming said.

In 2023, the “SGMA Effect” continued to drive down valuation and demand for farmland, reported ASFMRA’s 2024 Trends in Agricultural Land & Lease Values. The annual publication also noted weakness in the tree nut industry, once the main driver of cropland values, resulted in generally decreased orchard values statewide.

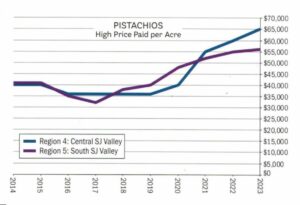

“Pistachio land once sold for $65,000 an acre,” said Ming. “Now it can’t get a bid for $40,000.” Potential land buyers are sitting on the sidelines, waiting to see where the market goes.

Falling prices

Pistachio prices remained profitable for years, peaking at an average of $3.57 a pound in 2014, said Bob Klein, recently retired manager of the Administrative Committee for Pistachios. Two years ago, pistachios remained the lone bright spot in the tree nut sector as prices for almonds and walnuts fell. But that’s not the case anymore. Although pistachio plantings have slowed sharply in the last 24 months, pistachio prices have dropped to below $2 a pound, pressured by burgeoning harvests and the high number of trees coming into production. For many pistachio growers, that’s below the cost of production, particularly those burdened by land debt.

But tree nuts aren’t alone in declining profitability. “Nothing [in California’s ag economy] is making money,” Ming said.

Increased inflation, interest rates and input costs

Prices for everything from water to fertilizer to equipment have soared. Labor, generally the second-highest farm cost, has risen to $24 to $25 an hour when you add in wages, health insurance, workers’ compensation insurance and labor contractor fees, said Romanini and Fanucchi. In the Buttonwillow area, about 25 miles west of Bakersfield, the cost of pistachio production ranges from $3,500 to $4,500 an acre, and that is if you have no debt on your land. Fortunately, Romanini owns his own land.

Bankruptcies and farming exits

In a sign of the declining profitability of pistachios, almonds and other crops, some of California’s biggest growers are bowing out. “Large bankruptcy offerings in late 2023 into Q1 2024 have made headlines, with others forecasted to come,” noted ASFMRA’s Trends publication. Among those is Trinitas Farming, LLC, a major Central Valley almond grower that filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection earlier this year. Also said to be looking to exit the farming business is the Assemi family, a major Fresno-based pistachio producer and processor. Assemi’s principal farming entity, Maricopa Orchards, and its processing facility, Touchstone Pistachio Company, are reportedly up for sale.

Good News

But it isn’t all gloom and doom for pistachios. Tilting the outlook toward the bullish side are booming export shipments.

“It’s shaping up to be a great year” for California pistachio exports, said Rob Yraceburu, president of Wonderful Orchards.

Speaking at ASFMRA’s agribusiness conference in March, Yraceburu said the industry will probably ship a record 1.1 billion pounds of pistachios this year, a “massive amount.” In fact, so much of the crop is being shipped, he added, “if we don’t have a billion-pound crop this year, we’ll have trouble. We’ll lose momentum.”

“We need a big crop this year to meet demand,” Yraceburu said.

The Wonderful Company is the world’s largest grower and processor of pistachios and almonds. The company grows 100,000 acres of the two tree nuts as well as pomegranates and winegrapes. It annually processes and markets 55% to 60% of California’s pistachios, including the crops of 900 independent pistachio growers. That makes Wonderful the leader in green nut’s pricing and shipping dynamics.

At the beginning of this season, Wonderful lowered its price to buyers by 30 cents a pound, or 8% to 10%, Yraceburu told the ASFMRA audience.

As intended, that price drop spurred sales. “We have had fantastic success,” he said.

China has been “the big win,” said Yraceburu. One-third of California’s pistachio crop harvested last fall is being shipped to the Asian giant. He added the increased demand for pistachios isn’t being seen in the U.S. That market’s not growing.

Despite pistachios’ export success, Yraceburu said there are potential impacts that could slow pistachio demand: geopolitical uncertainty, the push toward inexpensive, unhealthy snacking foods in the U.S. and concerns about California’s water supply and SGMA.

But the biggest risk is a trade war, he said. He recalled the tariffs the U.S. levied in 2018 against foreign countries, some of them California pistachio customers. Those buyers, including China, retaliated with tariffs of their own, making the tree nut more expensive to buy and limiting demand. Yraceburu expressed concern about the outcome of the U.S. presidential election and the potentially detrimental impact on trade if “one candidate” in particular should win. Donald Trump was president when the 2018 tariffs were imposed.

Back on the Ground

Back in Buttonwillow in late March, Fanucchi and Romanini gathered once again at the pistachio orchard they planted in 1980. The long-time friends discussed the ups and downs of farming and the survival mode of 2024. Although Fanucchi is well aware of the thin-to-negative margins for pistachios and other tree nuts, he sees opportunity ahead.

“People are not going to pull pistachio trees,” said Fanucchi. “They’re an ancient desert tree with an incredible root system and fantastic survival genetics. And we haven’t scratched the surface of export demand.”

Pistachio growers, however, must farm smarter to survive, he added. They must become more efficient in their operations and water use, in adopting technology and in lowering costs. For example, switching to mechanical pruning can save $600 an acre.

Sitting on a pickup tailgate surrounded by acres of pistachio trees, Romanini listened quietly. In the years after planting that first pistachio orchard, he significantly expanded his tree nut acreage. Most of the pistachio trees he put into the ground over the last two decades were the Kerman and Golden Hills varieties. Along the way, he and his sons, Mark and Brian Romanini, also experimented with other crops, even broccoli. These days, they grow almonds, cotton and corn along with pistachios.

“We’re in a holding pattern, waiting to see how all these commodities do,” Romanini said. “The water situation is scary. But I thank Carl for getting me started in pistachios. They have been our savior.”