Crown and trunk gall is one of the more common diseases in walnuts. It occurs primarily from wounds and is caused by a bacteria, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, that keys in on wounded plant cells, surviving in soil and gall tissue. While more common in younger trees, it can affect trees at any age, and seedling Paradox rootstock is especially susceptible.

During an update on the issue at a Quad County Walnut Day in Stockton, Calif. in February, Cameron Zuber, orchard crops farm advisor for Merced and Madera counties, discussed some of the causes, prevention and ways to treat, including manually removing galls or through use of available products.

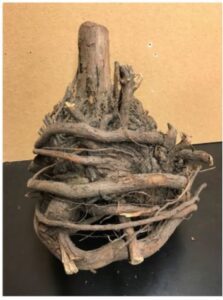

As the bacteria hones in on the wounded plant cells, the process causes the plant cell to grow in odd ways, creating the knotty masses that make up a typical gall seen on trees, Zuber explained.

“One thing I want to hammer home is that once this happens, the bacteria doesn’t need to be present for the gall to be there, because the change has already happened in the plant cell, but that doesn’t mean that other bacteria aren’t doing that continually to new plant cells that aren’t affected,” Zuber said.

He said crown gall can happen fairly quickly. While crown and trunk are the ones of most concern on crop impact, it can also impact roots, but there are preventative measures for all infection sites.

Causes and Preplant and Post-plant Considerations

While experts are still a bit baffled about where crown and trunk gall comes from, its transmission is less of a mystery and can come from a variety of ways, including crown gall growths, hands, pruners and shovels.

Zuber urges cleanliness of fields and tools, even if you don’t have a noticeable gall infection. “If you get one thing from my talk, keeping things clean, especially if you’re removing them, is highly important,” he said.

Prevention starts with cleanliness, but it doesn’t end there. Good measures include choosing resistant rootstocks, pre-plant fumigation, implementing at planting strategies, and after planting controls and treatments.

Generally speaking, Zuber said clonal rootstock are better than seedlings. Of those available, RX1 seems to have moderate to low resistance, VX211 is low, and while Vlach isn’t as low, it is generally a better option than seedling. He added Grizzly seems similar to RX1 or VX211 and potted might be less susceptible than bareroot, but noted these observations are preliminary in current trials. Generally, RX1 is a little bit better based on current research, but newer research may provide different or refined insights.

In preplant fumigation, Zuber said old research has shown Telone C-35 was pretty good at killing bacteria in the soil, but not the ones in the buried galls.

“As far as I know, there’s not a lot of newer research I’ve seen on a newer fumigant that is better at controlling this pest, but with fumigants and rootstocks, you’re not shooting for controlling just one disease; there’s a lot of things you’re balancing, so you kind of have to weigh what you’re hoping for,” he said.

At planting, he said it’s important to remember stressed trees are more susceptible to diseases. Since the disease triggers in on wounded plant cells, the less damage you can do to the roots or the trees at planting, the better. Pay attention to roots before planting to make sure they aren’t bound up around each other, causing damage to themselves, he said.

There are two things you can do to control root damage, Zuber explained. The first is keeping an eye on your planting crew to be sure they aren’t shoving root balls into the ground at planting.

“If you see them doing that, pull them off to the side to have a chat, because they’re twisting it into the hole, which means it’s winding up the roots, and you’re not going to really know it until a few years later,” he said.

Inspecting trees ahead of time helps. “I generally see it with bare rooted trees, so you want to be able to inspect each tree, and just look to see if any of the roots are oriented poorly,” he said. “You don’t notice until it falls over or it’s just generally impacted by disease.”

Sanitation and Removal

Once trees are in the ground, Zuber reiterated the importance of keeping tools clean, especially when pruning.

“Don’t put your pruners on the ground; keep them clean and disinfected,” he said, adding the typical calls he gets about galls are about infections higher up on the tree and have nothing to do with the crown since it is more common and expected.

Showing examples of gall’s that would be prime for removal, Zuber said when deciding which galls to remove, you want to focus on the ones that are worth the time and effort.

Timing for manual removal should be done in spring to early summer and away from any rain event. Tools for removal can include a good solid knife, a hatchet, a hammer, a torch and an approved disinfectant.

Removal steps begin with disinfecting all cutting tools that will be touching the wound and then cleaning as often as you can between cuttings.

For trunk galls, Zuber said he likes to make a perpendicular cut 1 to 1.5 inches below the gall and then a shallow parallel cut above the gall. You then need to cut behind the gall with a hatchet or knife. A hammer may help when using a hatchet to help cleanly cut behind the gall.

Once done with cutting, spray it with your chosen product, torch it and disinfect your equipment. He said this method doesn’t always do the trick and whether it’s worth it depends, but it could be a better option than removing the whole tree.

For crown galls, he said to excavate as much of it as you can see, work from the outer edge in, torch it and then use your tool of choice to hack away at it, ideally disinfecting as you can. He reiterated not to lay tools on the soil.

“Keep it clean, don’t push the soil back, leave it open, let it heal then push it back,” Zuber said.

After crown gall removal, monitoring should include watching for regrowth for at least one year and retreatment if new growth emerges, repeating as necessary.

Ultimately, Zuber said deciding if manual gall removal is worth it comes down to factors such as tree vigor, severity of galling and cost of treating vs replacing infected trees. If the decision to remove a tree is made, it’s important to remove as much of the roots from the prior tree as possible. Minimize wounds to the roots of new trees, and keep the crown area of the new tree dry.

Kristin Platts | Digital Content Editor and Social Correspondence

Kristin Platts is a multimedia journalist and digital content writer with a B.A. in Creative Media from California State University, Stanislaus. She produces stories on California agriculture through video, podcasts, and digital articles, and provides in-depth reporting on tree nuts, pest management, and crop production for West Coast Nut magazine. Based in Modesto, California, Kristin is passionate about sharing field-driven insights and connecting growers with trusted information.