Recent research on pistachio physiology is giving new insight into carbohydrate dynamics. Katherine Jarvis-Shean, a UCCE orchard systems advisor in Yolo, Solano and Sacramento counties, said research being led by Dr. Maciej Zwieniecki at UC Davis over the last eight years is helping piece together what’s actually happening during dormancy.

“We’ve always called winter dormancy a black box,” Jarvis-Shean said during a recent Madera-Merced pistachio day. “We don’t know what’s happening between the first day of November and February, we just know if it’s not cold enough, bad stuff happens, if it’s not warm enough, bad stuff also happens.”

The research is also helping scientists understand yield in carbohydrates better, some determinates of yield, and how to predict it. As researchers come to understand their findings, she said the next stage will be putting some solid numbers to how they can better manipulate carbohydrates in an on-farm setting and determine if and how that manipulation will pay off in a cost-benefit scenario.

Jarvis-Shean emphasized that these aren’t the kind of carbohydrates often associated with bread and pasta but ones called nonstructural carbohydrates. These components, which aren’t part of the plant’s structure or cell walls, serve as energy sources for the tree, aiding in cell growth. Additionally, they function as osmolytes, like how salts influence water dynamics and can act like signals, akin to hormones, which alter physiological activities.

“We’re talking about sugars and starches. Sugars, as you know, are a product of photosynthesis, the leaves are cranking out sugars, they’re the building block of starch, they’re an active part of biological cell activity, so they’re a signal molecule,” she said, “and because they are a signal, the level of sugar is actively regulated by the tree.”

She went on to explain starch serves as a storage form for carbohydrates, unlike signal molecules such as sugars that actively influence physiological activities. Starch breaks down into sugar when sugar levels are low and there is a need for energy.

In plant physiology, sugar is like cash on-hand, Jarvis-Shean said, something you keep in your wallet, and starch is like money you keep in your bank’s savings account.

The Dormancy Mystery

With yield being discernibly important for production agriculture, the UC Davis Carbohydrate Observatory was established to propel the research. Growers sent in twig samples regularly over the course of several years to be analyzed. Most pistachio locations that participated were in the southern San Joaquin Valley with a few in the higher north.

“They would analyze how much carbs were in these twigs, and in the different components, how much is in the bark, how much is in the wood center, and how much sugar and how much starch in the different components,” Jarvis-Shean explained.

By following the samples over time, they hoped to have a better understanding of how trees use carbohydrates for vegetative and fruit growth and how they are used for dormancy defense against pathogens and other stressors. Until a couple years ago, she said it was a subject that had relatively little data.

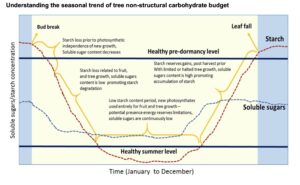

When analyzing the data on how carbohydrate levels fluctuate throughout the year, Jarvis-Shean said there was a consistent pattern observed. Carbohydrates declined from the end of dormancy to their lowest point at bud break before rising again. Starch levels in bark remain low and stable for most of the year, peaking only in the fall, whereas sugar levels in bark are low in spring and then stabilize. In wood, starch levels are lowest during bud break and peak in the fall, while sugar levels are lowest around bud break and then remain stable.

“What’s happening here is the leaves are pumping out sugars, the plant is sending those sugars right away in the growing fruit and vegetation, that’s what’s happening over the course of the growing season,” she said. “If there’s any spare, that’s going into starch.”

Going into winter, she said the tree knows whatever is leftover needs to go into storage, so while it’s easy to think of dormant trees as just sitting there doing nothing, they still require energy.

Can Carbohydrates Predict Bloom?

A consistent trend in the study led by Dr. Or Sperling was seen at bud break across almond, pistachio, walnut, apple and even peach, where there was a last-minute upsurge of starch and a decline in sugar.

“What’s exciting about this is that this is related to two different enzymes, this is about starch synthesis, so taking that sugar and making it starch, and starch degradation, a different enzyme, which takes the starch and turns it back into sugar,” Jarvis-Shean said.

That’s significant because the two enzymes have very different temperature responsiveness, and they’re managed in different concentrations in the trees.

Chill portions, or the dynamic model for counting chill accumulation, something Jarvis-Shean said was established in the 1980s and 1990s, speculated there were two chemicals that had different responsiveness at different temperatures, but scientists didn’t really know why.

“We think these are those two imaginary enzymes they were talking about; when it’s warm, we get this enzyme that turns sugar into starch because that most often happens during the growing season when leaves are pumping out sugar, because they’re photosynthesizing a lot,” Jarvis-Shean said. “When it’s cold, we get starch degradation to turn starch into sugar because sugar also acts as a natural antifreeze.”

All these aspects were combined to come up with an equation to help predict bloom timing, she explained. Coming out of a cold winter, you need less warm time to get bud break in the spring, but the opposite happens with a warm winter because starch synthesis is overactive in warm temperatures in trees and so less of the starch synthesis enzyme gets made.

“So, you’ll get less of it coming into spring to get the desired amount of starch synthesis to happen,” she said. “The result is you need more warmth than in a normal spring to get bloom.”

She noted it’s always been known colder winters require less heat for bloom, while milder winters require more heat, but the study provides new information in the identification of the actual mechanisms behind this observation, which had not been previously established.

“So, you can put those mechanisms together and build a mechanistic model of what’s happening with bud break timing,” she said.

Broadly speaking, she said, the more sugar you have going into winter, the earlier bud break will be; the lower your sugar, the later bud break will be.

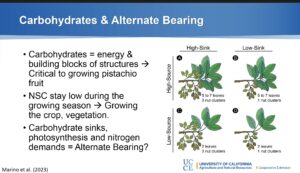

Related research by UCCE’s Giulia Marino also examined the role of carbohydrates in yield, and specifically addressed the alternate bearing years pistachio growers must contend with. That research looked at carbohydrate sinks when nuts are in high fruit set and sources when there is an abundance of leaves, which are available to fill those sinks.

Marino explained the tree will boost photosynthesis to meet the high carbohydrate demands of many fruit sinks during kernel fill, while low carbohydrate sources decreased photosynthesis after kernel fill.

“This is an interesting additional layer on what’s driving alternate bearing and what we might be able to do about it, or manipulate it, understanding that carbohydrates drop, that there wasn’t as much carbohydrates to support the bud growth for the fruit bud that would be making the fruit in the following year,” she said. “So, because those hungry sinks were taking a lot of the nitrogen out of those leaves, there wasn’t as much photosynthesis after that to make healthy buds for the following year.”

While some of this link between yield and carbohydrates is related to this alternate bearing-carbohydrates-bud health relationship, carbohydrates and yields are related in on-years, too. Jarvis-Shean said this relationship has been noted across other tree nut crops as well, including almond and walnut.

“It’s not just about alternate bearing; there is this general relationship found across multiple nut crops that found the more carbo loaded you are going into winter, the stronger your yields will be the following year,” she said.

What It Means for Production

The chill-heat-carbohydrates relationship helps to understand why warm winter temperature, and why warm wood and buds from having less fog, would lead to delayed and protracted bloom, Jarvis-Shean said.

“That’s a mechanism we just haven’t understood that well before,” she said.

It explains several things, including why chemical sprays that interfere with respiration have a dormancy manipulation-related effect and why reflectants that keep wood temperature lower could help compensate for lower chill.

For this issue, she said future research should determine how warm temperatures need to be to justify the cost of reflectants and identify the optimal timing for applying dormancy-breaking treatments.

She also emphasized the strong relationship between late-season management and carbohydrate yield in fall and winter suggests strategies aimed at carbohydrate loading could enhance both the timing of bud break and long-term yield outcomes.

While research hasn’t perfected an exact method for carbohydrate loading yet, Jarvis-Shean said it suggests maintaining healthy leaves on trees through October to maximize sugar production before the leaves drop.

She notes for pistachios, particularly with young trees, it’s crucial to strike a balance to avoid keeping the trees too active and risking juvenile tree dieback.

“So, we don’t want to keep them super vigorously growing through October, but we do want those leaves on there pumping out carbohydrates,” she said.

Growers interested in learning more about how your farm lines up with the state’s data can visit the UC Davis Carbohydrate Observatory website or contact Maciej Zwieniecki at mzwienie@ucdavis.edu or by phone at (530) 752 9880.

Kristin Platts | Digital Content Editor and Social Correspondence

Kristin Platts is a multimedia journalist and digital content writer with a B.A. in Creative Media from California State University, Stanislaus. She produces stories on California agriculture through video, podcasts, and digital articles, and provides in-depth reporting on tree nuts, pest management, and crop production for West Coast Nut magazine. Based in Modesto, California, Kristin is passionate about sharing field-driven insights and connecting growers with trusted information.