Pistachios have been growing wild in the Middle East as far back as 7,000 B.C., based on recent archeological discoveries in Turkey.

According to legend, the Queen of Sheba was a big fan of pistachios. She decreed them an exclusively royal food, and expressly forbade commoners from consuming the nut. As the king of Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar ordered pistachio trees to be planted in the famous Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

Pistachios are one of only two nuts mentioned in the Bible. Genesis 43:11 reads, “Then their father Israel said to them, ‘If it must be, then do this: Put some of the best products of the land in your bags and take them down to the man as a gift, a little balm and a little honey, some spices and myrrh, some pistachio nuts and almonds.’”

As empires grew and explorers travelled, pistachios were eventually taken throughout Europe and Asia. By the late 18th century, pistachios had become common in most of Europe, where they were incorporated into a wide range of recipes. In France, pistachios were used to season sausage and other meats. The Complete Confectioner, published in London in 1789, which describes itself as “a ready assistant to all genteel families,” includes recipes such as pistachio nut biscuits, white pistachio prawlongs (pralines) and pistachio ice cream.

Pistachios Arrive in the U.S.

According to Eric Hansen in his article “In Search of the Mother Tree” in the magazine Saudi Aramco World, the first pistachio trees were introduced to the U.S. in 1805 “by the New Crop Introduction Division of the newly founded government.” No other source included this account, however.

Most historical accounts credit Charles Mason with introducing the first pistachios into the U.S., bringing seeds to California in 1854. This was shortly after Mason, the first Iowa Supreme Court Chief Justice, a grower and a distributor of experimental plant seeds, was appointed Commissioner of the U.S. Patent Office.

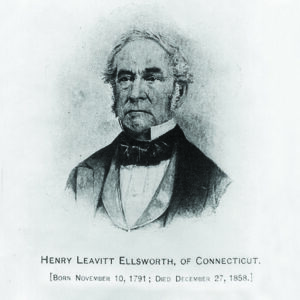

Mason’s predecessor as commissioner, Henry Leavitt Ellsworth, was also interested in collecting seeds and plants from around the world. Ellsworth would use consular services to gather seeds from other countries and then distribute them for planting in the U.S. Without funding, this effort was done on a small scale. In May 1854, however, Congress appropriated $10,000 to collect and distribute seeds and cuttings under the supervision of the Commissioner of Patents, who by that time was Charles Mason.

Pistachios from France

“Probably the first crop of this nut grown on the Pacific Slope was produced in 1881 on trees belonging to G. P. Rixford of Sonoma, Calif.,” wrote S.B. Hedges in Nut Culture in the United States, his report to USDA in 1895. “The trees were imported from the north of France in 1875. They are small (about 8 to 12 feet in height), but are thrifty and vigorous… Its culture may well be tested further in California.”

Unrecognized Potential

In the 1889 edition of The California Fruits and How to Grow Them, Edward J. Wickson wrote that after several years of research, it was “likely that erelong (in the near future) a commercial product of pistachios may be attained in California.” Wickson would later become dean of the College of Agriculture and director of the Agricultural Experiment Station at the University of California.

Wickson wrote in the 1908 edition of the same manual, “The pistachio needs more time to declare its California career.” In 1919, he wrote “commercial results are only just beginning to be attained.” He acknowledged, however, that at the time, none of the varieties were adapting well to existing conditions. As a result, he considered the nut “a marginal crop in California’s agriculture” despite the fertile soil, hot, dry climate and moderately cold winters of California’s Central Valley.

USDA was slow to recognize the full potential of the pistachio. Its 1915 Yearbook reported, “The Chinese pistache (pistachio) tree gives promise of being a fine shade tree for large areas in the South and Southwest. It grows to be a stately tree with a dense head of gracefully pinnated foliage… It resists drought wonderfully well and will be especially appreciated in the warmer semiarid parts of the U.S.”

The Chico Seed Orchard

The Chico Seed Orchard in Chico, Calif. was established in the early 1900s as the Plant Production Station. It became part of the Agricultural Research Service in 1904, with the purpose of conducting plant breeding research and introducing plants from all over the world into the U.S.

Pistachio trees were studied there for almost 30 years. The first pistachios to be tested were the Buenzle, Bronte, Minasian, Red Aleppo, Sfax and Trabonella varieties. None of them, however, were deemed likely to become successful pistachio nut varieties in the U.S. The Red Aleppo and Trabonella were the most promising, but both had insufficient yields.

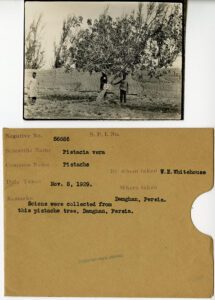

In 1929, the Office of Foreign Plant Introduction made developing better pistachio varieties one of its main objectives. The effort resulted in three promising varieties: Kerman, Damghan and Lassen, all recently brought from Iran by William E. Whitehouse.

The considerations included the time of year of the bloom (to avoid spring frosts) and tree performance. Eventually, Kerman became the preferred variety.

After decades of studying pistachios, research ceased at the Chico Seed Orchard.

“Very few of the original grove trees still exist onsite,” said John Winn, national press officer for the U.S. Forest Service. “We no longer have a functioning pistachio orchard as they were removed in 1990 in preparation for future Douglas fir orchards.”

Explorer Frank Nicholas Meyer

In 1905, Frank Nicholas Meyer, a plant explorer for USDA, set sail for China with task of sending back “every fruit, nut or vegetable that he thought would have value in this country.” In addition to China, Meyer visited such places as Korea, Siberia, and Turkestan, mainly by walking long distances.

Along the way, Meyer was often attacked, robbed and threatened. He was also confronted by bears, tigers and wolves. During China’s cultural revolution of 1911, he was mistaken for being on both sides of the revolution. In June 1918, Meyer boarded a steamer on the Yangtze River bound for Shanghai and was never seen again.

As a result of his 13 years of traveling, more than 680 species and varieties of plants and seeds were brought to the U.S., including the Chinese pistachio (Pistacia chinensis) and the lemon that now bears his name.

Farjalla Zaloom

In the late 19th century, Farjalla Zaloom, an immigrant from Syria, started importing pistachios into the United States, 25 to 50 lbs. at a time, according to an article by his son, Joseph A. Zaloom, in the June 1934 issue of Automatic Age. He wrote that “Americans enjoyed them” and “wanted more.

“In 1922, Salim F. Zaloom (Farjalla’s other son) developed and patented the process of applying a thin, pure white layer of salt on the shell,” wrote Joseph Zaloom. “This preserved the delicate nut against spoilage, greatly improved the flavor and made the nuts wonderfully attractive.”

The article described the Zenobia Company, the Zalooms’ New Jersey-based family business, as being the largest importer and roaster of pistachios in the U.S. Five years later, however, the company was overstocked with pistachios, with 1 million pounds in its inventory.

“Then a New York vending machine operator called at the company’s office with the idea that he could sell white pistachio nuts in his machines,” the article continued.

The Zaloom family called the vending machine operator “crazy” because, after all, pistachios were considered a high-priced product at a cost of 32¢ a pound. The operator was undeterred, however, arriving at the Zenobia offices the next day and paying $4.60 for 5 pounds of pistachios. His purchases from Zenobia for an increasing number of vending machines eventually reached 5,000 lbs. for 1,000 machines.

As other operators learned of his success, they decided to sell pistachios in their own machines, and the demand for pistachios resulted in Zenobia’s stock of 1 million pounds of pistachios being virtually sold out.

By the 1940s, vending machines in busy locations such as train stations, restaurants, and bars were responsible for 85% of total pistachio sales. A well-known advertising slogan of the time was “A dozen for a nickel.”

“The pistachio nut became well-known and appreciated in the early 1930s,” wrote Joseph Zaloom. “Undoubtedly, the vending machine became a common medium for making peanuts, cashews and pistachios more accessible to American customers.”

During the 1930s, the Zenobia Company was sold to John Germack, also an immigrant from Syria. Under his leadership, Zenobia dominated the U.S. pistachio business. During World War II, he arranged for Liberty Ships to bring pistachios across the Atlantic Ocean, while avoiding hostile German submarines. As a result, Zenobia had the country’s only supply of pistachios during the war.

Red Pistachios

When most pistachios were imported from Iran and other countries, a red dye was commonly used to cover up any defects during production. The downside of the dye was that the red color on imported pistachios would rub off on hands and mouths. U.S. companies would also use a red dye to sell to consumers who had come to expect the color on their pistachios.

As the U.S. pistachio industry grew and producers started using newer mechanized harvesting processes to pick, hull and dry the nuts, stained shells were no longer an issue, eliminating the need to dye the nuts. Today, most red-dyed pistachios (if you can find them) are sold as novelty items.

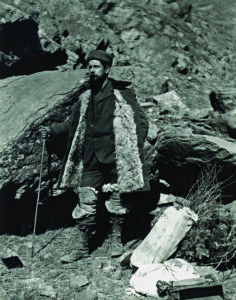

William E. Whitehouse

According to his obituary in The Washington Post, William E. Whitehouse, a longtime official of USDA, “is considered by many to be the father of the American pistachio nut industry.”

In 1929, Whitehouse was sent to Iran with the goal of returning with pistachio seeds that could be successfully planted in the U.S. The result of his mission was 20 pounds of various pistachios brought back to the U.S. (Some sources say “smuggled.”)

Most of the seeds were planted at the Chico station, and when the trees were evaluated, the “Kerman” showed the most promise. Named after a town in Iran’s central plateau, the single pistachio that eventually developed the U.S. pistachio industry was found in a pile of drying nuts in the town of Agda.

In 1976, the first commercial crop of Kerman pistachios harvested in California produced 1.5 million pounds. Less than 40 years later, Kerman had become a billion-dollar agricultural product.

Politics and the Pistachio

The U.S. pistachio industry grew exponentially as the result of a change in the tax code and the response to a hostage crisis.

In 1969, the U.S. Congress revised the federal tax code to eliminate tax shelters for both almond and citrus fruit growers. Pistachio trees, however, were still acceptable tax shelters to the IRS. As a result, many California growers replaced their almond and fruit crops with pistachios.

Iran was the world’s leading pistachio grower throughout the 1970s, but events in 1978 would soon change that. On Nov. 4, 1978, a group of students protesting the U.S. support of the Shah of Iran stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and took 66 American hostages. President Jimmy Carter responded by announcing an embargo on goods from Iran, including pistachios.

In 1986, the embargo was modified to allow some Iranian goods, but by that time the U.S. pistachio industry had become a major pistachio producer. Since 2008, the U.S. has been the world’s leading grower of pistachios.