Bacterial infections such as almond blast and walnut blight pose significant challenges for growers. Bacterial blast is primarily caused by Pseudomonas syringae pathovar syringae, a bacterium that is responsible for approximately 95% of the infections observed, whereas walnut blight is caused by Xanthomonas arboricola pv. juglandis.

The bacterium of almond blast typically lives on the surface of plants without causing problems; however, under cold or stressful conditions, it becomes pathogenic, attacking the flowers, buds and shoots. These conditions often manifest in symptoms, such as blossom blast and shoot dieback as well as leaf and fruit spotting, and can be particularly damaging in young orchards between two to eight years of age. In the worst cases, shoot dieback can be seen with significant loss of spurs, according to Jim Adaskaveg, professor and plant pathologist at UC Riverside.

Adaskaveg has conducted extensive studies to understand and combat these diseases and spoke about his findings during the North Valley Nut Conference in Chico, Calif. earlier this year.

One diagnostic method for blast is the absence of fungal mycelium or sporulation typically occurring with brown rot or green fruit rot infections, with symptoms instead appearing as the sudden death of leaves, blossoms and spurs. Adaskaveg noted during the canker phase, typically in late winter and early spring, peeling back the bark reveals cankers with discoloration and necrotic flecks, and field diagnosis is often conducted by scent.

“When you go to smell it, it has a very sour smell to it,” he said.

Occurring especially on stressed trees and disseminated by rainfall to natural plant openings, bacterial blast and canker are not limited to almonds but also affect a variety of fruit crops, including citrus and stone fruits. While peach is less susceptible, some varieties and rootstocks are more susceptible than others, including Mariana 2624 and the peach-almond hybrids Hansen, Nickels, Cornerstone, Titan and Bright’s.

Adaskaveg and his team are managing these diseases through a strategy that primarily focuses on testing a variety of bactericides. He presented data demonstrating the effectiveness of bactericide treatments in combating bacterial blast, highlighting several trials that evaluated experimental materials, including one on Fritz in Colusa County and one on Independence in Stanislaus County.

He said they specifically chose to work with a unique mode of action called Kasumin, a commercial formulation of the bactericide kasugamycin, a FRAC Code 24, because it is separate from all medical antibiotics.

“There’s no overlap, it is specifically being used for plant agriculture; there’s no human or animal usage, so it’s not really going to affect what happens in the medical world,” Adaskaveg said.

The experiments showed applying Kasumin prior to a forecasted frost can significantly reduce the incidence of the disease and help preserve nut yield.

“We actually did nut counts later in the year, and we can see there are more fruit that survive, there was less blast, so you got more nuts,” he said, noting this was how they determined Kasumin was working against bacterial blast in the Colusa orchard.

The bactericide is applied using an air-blast sprayer seven days prior to a forecasted frost event, Adaskaveg explained. The closer the application to the frost period, the higher its performance.

He noted it’s also important to know that unlike some other materials, these applications are designed to only last about seven days.

“So, if you put it on, you have to be as close to the forecasted frost as possible to get the best effect of disease control,” he said.

Referring to the study in Stanislaus County, Adaskaveg said Independence is highly susceptible to bacterial blast. Following a similar process as the Colusa study, Kasumin also showed a reduction there. He stressed achieving 100% control with bactericides is challenging, unlike with some newer fungicides, yet significant reductions in disease levels are still attainable.

Adaskaveg suggests maintaining tree health and vigor through proper nutrition, preplant fumigation, postplant nematicides and removing dieback can be a good way to help protect against bacterial blast and canker.

He said a Section 18 emergency request was submitted for Kasumin, specifically for bacterial blast of almond, with applications requested from bud break to petal fall. It became effective Feb. 2, 2024, and was valid until April 15, 2024.

Walnut Blight Management

Fruit infections from walnut blight result in black, irregular lesions on the hull with infections progressing into the kernel, causing direct crop loss, Adaskaveg said. The pathogen survives between the bud scales of living flower buds (both in male catkins and female pistillate flower buds) and in cankers, or dead tissue.

He said many people don’t realize it can survive in cankers.

“Some of these newer varieties get cankers in the wood, and the pathogen is also overwintering in those types of situations,” he said.

He observed symptoms such as spur dieback and blackened catkin infections in the Tulare variety, noting the pathogen can be isolated from cankers and catkins, but isolation of the organism from female flowers is particularly easy.

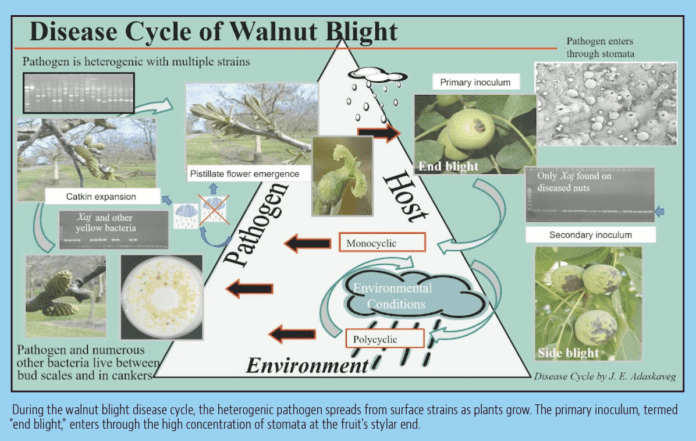

Adaskaveg explained the disease cycle of walnut blight, noting the pathogen is heterogenic with multiple strains residing on the surface, spreading as the plant and flowers grow. He described the primary inoculum, often the initial cause of the disease, as “end blight” because there is a high concentration of stomata around the stylar end of the fruit that serve as entry points for the pathogen.

“The bacterium likes to get in through those points of entry,” he said, adding secondary infections called “side blight” are initiated from the inoculum that ooze out of primary infections and will occur with rain or other wetness events, such as when irrigation is hitting the tree.

Walnut blight typically exhibits a monocyclic phase, meaning only one cycle occurs without rain, but transforms into a polycyclic cycle with multiple infection periods if rains persist, he added.

While copper has been the standard treatment for walnut blight for many years, mixtures of copper with mancozeb (Manzate or Dithane) registered in the 1990s is the current standard, Adaskaveg said. Still, we are concerned with mancozeb continuing to be available due to tentative import tolerances after the EU cancelled mancozeb for the European walnut industries.

“We’re trying to fight that; they want to lower the MRL (maximum residue limits) numbers to what they cannot actually measure accurately, and we think that’s unfair,” Adaskaveg said.

With that in mind, alternative methods need to be considered, he said. Currently, one of those materials is dodine (Syllit) that was recently registered as an alternative to mancozeb. It can be mixed at low labeled rates with copper or with kasugamycin. Other materials they looked at included biologicals like Blossom Protect, Serenade, Regalia, Dart and essential oils that reduce the disease under low disease pressure but are less effective as conventional treatments under high disease pressure with weekly rains and warm temperatures.

“The goal is to have multiple materials that can be rotated or mixed with each application and prevent the selection of resistance, like what happened with copper,” Adaskaveg said. “We know that if we overuse any of the products, bacterial pathogens (like the walnut blight pathogen) can develop resistance.”

Adaskaveg said managing blight will remain a top priority in walnut production, particularly if the climate changes to wetter and warmer conditions. He noted ongoing efforts include development of effective alternatives that perform well in favorable environments, discovery of new modes of action against bacterial pathogens and identification of synergistic mixtures for rotational use.

He also noted the challenges of navigating the registration and regulatory processes with agencies like the EPA to bring new bactericides to the walnut industry. The EPA has been particularly difficult when it comes to registering bactericides because of the hypothetical potential to select for human pathogen resistance when used in the environment such as in plant agriculture. Although this has been shown not to occur because of the short persistence of most antibiotics in the environment before they degrade to inactive forms, hypothetically it remains a possibility.

Fall Considerations

Adaskaveg said monitoring for disease levels over the summer and into the fall is also important in planning next year’s disease management programs. High disease levels in the current year can result in higher inoculum levels in buds and cankers that overwinter the pathogen, creating higher risk next spring season. After the fruit are harvested, bud populations can be estimated in the fall and winter to determine if a more aggressive spray program is needed during next year’s spring flowering period.

Planning a mixture rotation program of different modes of action is the best course of action. Copper-mancozeb, copper-kasugamycin, kasugamycin-mancozeb and copper or kasugamycin mixtures with dodine (Syllit) at low labeled rates (e.g., 16 fl oz/A) are excellent combinations for managing walnut blight. Planning a three- to four-application program for early blooming varieties or a two- to three-application program for late-blooming varieties under low to high disease pressure will keep walnut blight at low levels.

Kristin Platts | Digital Content Editor and Social Correspondence

Kristin Platts is a multimedia journalist and digital content writer with a B.A. in Creative Media from California State University, Stanislaus. She produces stories on California agriculture through video, podcasts, and digital articles, and provides in-depth reporting on tree nuts, pest management, and crop production for West Coast Nut magazine. Based in Modesto, California, Kristin is passionate about sharing field-driven insights and connecting growers with trusted information.