Tree nut orchards and noxious weeds are not a good combination for maximizing production. Uncontrolled weed populations can steal water and nutrients from trees, harbor vertebrate pests and hamper harvest operations. Controlling weeds in their orchards is an ongoing concern for growers who can face new weed challenges every year.

Looking forward to 2025, tree nut growers might experience new invasive weed species, increasing herbicide resistance, and new restrictions on some herbicides. Innovations in weed control include using electricity to zap weeds, planting hedgerows and using sheep to for weed control.

1. New Weeds, Weed Shifts

University of Arizona Cooperative Extension has put out a warning about Stinknet, an invasive African annual weed, which is spreading in Maricopa, Pinal and Pima counties and has been found in California. Oncosiphon pilulifer, sometimes also known as globe chamomile, is a member of the sunflower family. This plant has spherical yellow flower heads consisting of many tiny flowers. Crushed foliage has a pungent, turpentine-like odor.

UCCE Weed Specialist Jorge Angeles in Tulare County said Stinknet has been found in Riverside County and has spread in Los Angeles and San Diego counties. There are no reports of this weed being present in the Central Valley. Angeles said herbicides, including glyphosate, are effective.

Angeles and Mandeep Riar, UCCE weed specialist in Kern County, said even if no new weed species that would affect tree nut orchards are currently on the horizon, growers have plenty of known weeds to battle in orchards. Shifts in weed populations can occur from year to year, requiring changes in weed management plans. Angeles and Riar listed hairy fleabane, horseweed, Johnson grass, Bermuda grass, mallow and Palmer’s amaranth as the weed species causing the most problems in tree nut orchards.

“It can change from year to year, as weed populations shift, from broadleaf weeds to grasses,” Riar said.

Angeles said alkali weed, Cressa truxillensis, which popped up in orchards in the last few years, continues to plague pistachio growers in the southern Central Valley and is spreading. This native, perennial plant is part of the morning glory family. Standard orchard floor management practices and herbicide applications do not keep this weed in check. This weed can re-grow after herbicide treatments.

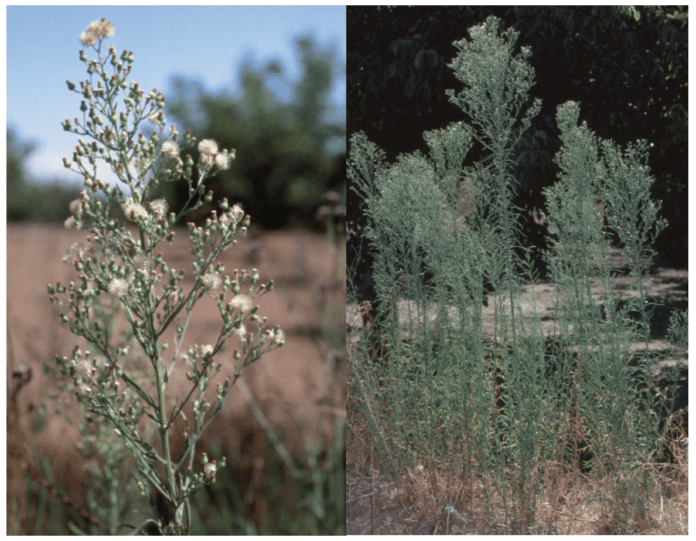

Silverleaf nightshade, Solanum elaeagnifolium, is a perennial weed native to South America, Mexico and the southwestern and southern U.S. It has become widespread in California, invading tree nut orchards and other agricultural systems. High temperatures, scant moisture and saline conditions have little effect on silverleaf nightshade growth. Pistachio trees planted in fields containing high volumes of seed can struggle to compete with this weed.

Little Seed Canary Grass and Common Chickweed are two new problematic weed species in small grain crops.

2. Herbicide Resistance

Rotating use of appropriate herbicides with different modes of action can slow the development of resistance in weeds. Relying heavily on one material or tank mix over time causes weeds to develop resistance in-season and from one season to the next.

According to the International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds, worldwide there are 523 unique cases of resistant weeds. Of the 269 species, 154 are dicots and 115 are monocots. Weeds are resistant to about 21 of the 31 known sites of action, affecting 99 crops in 72 countries.

Glyphosate resistance is well known in horseweed, fleabane, ryegrass and junglerice and suspected in Palmer amaranth, lambsquarters, threespike goosegrass and sprangletop.

UCCE Weed Science Specialist Brad Hanson noted in a UC Weed Science publication there are also resistance concerns with Paraquat and Glufosinate. There are populations of annual bluegrass (Poa annua), horseweed (Conyza canadensis), annual or Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum), junglerice (Echinochloa colona),and hairy fleabane (Conyza bonariensis) that have developed resistance to glyphosate in California.

Angeles said watching for weed escapes, those not killed by herbicide applications, is important in reducing herbicide resistance. Management also involves scouting early and removing weeds before they produce seeds. Angeles said it will take an integrated approach to control resistant weed populations. Early detection and identification of weeds in their early stages of growth is key, Riar said. Growers can check the UC Weed Research and Information Center to assist with weed identification.

3. New Herbicide Restrictions

While this restriction does not target specific products, beginning in 2025, California Department of Pesticide Regulation plans to launch a notification system for applying restricted use materials. This regulation creates an online map for public access of planned applications.

Although the herbicide Dacthal (DCPA) was banned for use in agriculture this year, Angeles said no major changes in herbicide use are on the horizon. Those materials with residual action are under scrutiny, he added, due to overapplications. Rather than stick with one herbicide, he said it is better to rotate chemistries.

4. Targeted Grazing in Orchards

Using sheep and goats to control weeds in orchards is not a new practice but is returning to the tool box. Julie Finzel, UCCE range, natural resources and livestock advisor in Kern County, said in organic systems and where management is seeking to reduce herbicide use, targeted grazing is now gaining more attention as a weed control tactic. Finzel, who has been conducting research on targeted grazing, said food safety concerns with livestock are addressed with removal of animals 120 days prior to first shake. Finzel also gathered data from growers and grazing providers to do an economic analysis of targeted grazing.

Typically, sheep are brought into orchards to graze down winter weeds. Variations in weather from year to year impact demand for livestock weed control. In wet years, where there is more vegetation in orchards to control, livestock owners may have better choices for feeding their animals. In drought years, targeted grazing companies may be looking for scarce feed options. She also noted that at mature stages, silverleaf nightshade and amaranth would not be eaten by sheep.

5. Electric Weed Control

This weed control option involves power generated by a tractor PTO shaft that drives a generator which converts mechanical energy into electrical energy. An application unit uses electrodes to channel the current into plants as it moves through the orchard. As the high voltage passes through the plant and down to the roots, heat is generated, causing cell membrane rupture and plant death.

Stage of weed development, types of root systems, weed population density and soil moisture determine efficacy of electric weed control. Young and creeping weeds are easier to kill with electricity. Plants with more woody tissue have higher resistance.

Tong Zhen, a graduate student at UC Davis, said the UC Davis team is collaborating with Oregon State University and Cornell University researchers working on a similar machine on different crops. At Davis, Zhen said they are using a Zasso ElectroherbTM in an organic almond orchard and organic blueberry fields. In the two-year-old almonds, Zhen said they have found effective weed control, making passes in the orchard once a month during the growing season. No crop injury has occurred. Drawbacks they have confirmed include variable moisture levels, which can affect efficacy, and potential for fire in dry weed residue.

There is potential for commercial availability in the future, Zhen said, as they are working with Sacramento-area growers, and more field trials will be conducted in the upcoming season.

Cecilia Parsons | Associate Editor

Cecilia Parsons has lived in the Central Valley community of Ducor since 1976, covering agriculture for numerous agricultural publications over the years. She has found and nurtured many wonderful and helpful contacts in the ag community, including the UCCE advisors, allowing for news coverage that focuses on the basics of food production.

She is always on the search for new ag topics that can help growers and processors in the San Joaquin Valley improve their bottom line.

In her free time, Cecilia rides her horse, Holly in ranch versatility shows and raises registered Shetland sheep which she exhibits at county and state fairs during the summer.