As discussed previously in West Coast Nut and on UC’s SacValleyOrchards.com blog, walnuts are one of the highest-chill-requirement tree crops in California. Multiple recent winters have fallen short of the chill needed for a tight, economical walnut bloom (e.g., 2014, 2015, 2020). In the next 20 to 40 years, Central Valley walnut orchards will get 14% to 20% less winter chill than in the 1950s, making it likely that ‘Chandler’ orchards will not meet their chilling requirement at least 1 out of 10 years in most of the Central Valley in the coming decades. Besides developing lower-chill varieties, is there anything we can do to help walnuts through these low-chill winters? Recent UC research funded by the California Walnut Board and the California Department of Food and Agriculture indicates there are several promising tools.

Many of you may be thinking, “You want me to put on another spray? In this economy!?!” I know prices are tight, and walnut growers are still clawing their way out from years of barely being able to afford to just irrigate and harvest. The tools I’ll talk about here aren’t for every orchard every year in every situation. What’s more, our understanding of these tools and how to best utilize them is still evolving. As a research scientist, I’d be most comfortable studying these tools for many years to generate an enormous pile of data and a definitive recipe for success. But given these tools are currently on the market, and many growers are wondering if and how they may fit into their management, I’m sharing below what we know so far, acknowledging our understanding will evolve as we get more experience with them.

Early Research Showed Us Tools to Move Budbreak

Rather than wait for low-chill years to come along, we created warm winter conditions in large, open-top chambers we built around mature Chandler trees at the UC Davis campus. These trees were coupled with unheated trees that got sufficient winter chill. Approximately 30 to 40 days before budbreak, dormancy-breaking treatments were applied to different scaffolds in each tree. We then monitored budbreak over many weeks.

Over the course of four years, we tested hydrogen cyanamide, specifically Dormex®, a blend of nitrogen compounds marketed as Erger®; an analogue of the plant hormone cytokinin, marketed as Mocksi®; and calcium ammonium nitrate (CAN-17), all of which were compared with a water control. Dormex is the only one of these products currently labeled for use as a dormancy breaker in walnuts (see label for use details). Erger and CAN-17 are labeled as fertilizers. In terms of budbreak timing, we found Dormex at 2% and 4% and CAN-17 at 20% could prompt heated scaffolds to behave like they had received enough chill, whereas Erger at 6% and CAN-17 at lower rates (5% and 10%) only partially compensates for lack of winter chill. No effect was seen using Mocksi over two years.

Decreased budbreak is also a symptom of low chill, so we looked at whether any products could compensate for that. Our years of research in heated trees showed Dormex at 2% often significantly increased the percentages of buds that opened on heated scaffolds, whereas Dormex at 4% often increased budbreak numerically, but not to a level that statical analysis could differentiate from the control. CAN-17 often had numerically higher budbreak, but not to a degree that we can say was significantly different from our control.

Grower Trials: Similar Budbreak Story, Yield Is More Complicated

Taken all together, our tented tree trials indicated hydrogen cyanamide and CAN-17 were worth testing at a field scale. With generous collaboration from two grower hosts, we’ve spent two years so far comparing Dormex at both 2% and 4% and CAN-17 at 20%, monitoring budbreak timing, maturity timing, yield and quality. The two Chandler orchards we’re working in are fairly representative of the industry. One is a healthy orchard just a few years into its prime yielding years (10th leaf) in Glenn County and the other, planted in the hills above Arbuckle, is a few years past its prime, with some limb and spur dieback from tight spacing and Botryosphaeria.

So far, budbreak timing results have been in keeping with what we saw in our tented tree trial. In spring 2023, after a high-chill winter, budbreak was two to three days earlier across treatments when compared with the control. In spring 2024, after a good but not luxuriously high-chill winter, budbreak was five to six days earlier at the Glenn County site and 8 to 11 days earlier at the Arbuckle site.

This year, we also looked to see if this earlier budbreak resulted in earlier maturity. We found at the Glenn County site 100% packing tissue brown (PTB) occurred 10 to 11 days earlier in the treated trees than the control, with no difference between treatments. At the Arbuckle site, there was a numeric trend of 100% PTB being a few days earlier, but it wasn’t significantly different from the control. This points to a potential interesting side-benefit for these dormancy breaking tools: The ability to shift harvest timing for growers with too many acres of Chandler to harvest at once. Pairing these tools with ethephon later in the season could go a long way toward relieving the logistical stress associated with most of the industry being dominated by Chandler. That said, we need a few more years of data to get a better sense of how consistent these results can be.

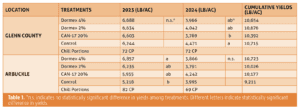

Our yield results have been both interesting and surprising (Table 1). Last year, even when chill was more than adequate, we saw a significant increase in yields, 1,600 lbs on average at the Arbuckle site associated with Dormex at 4%, and an increase in yields, though not statistically significant, in the other two treatments at Arbuckle (700 to 1,000 lbs), and in all treatments, though not significant, at the Glenn County site (400 lbs). Though this lack of statistical significance meant it wasn’t a slam dunk yield win for these treatments, the consistent increase across sites had us excited, particularly given we’d previously seen increased budbreak from these treatments in our tented trees. This year, however, we were very surprised to see yields were actually the same or lower in our treatments than the control. Yields were 400 to 700 lbs lower than the control at the Glenn County site, statistically significant with CAN-17, and 200 lbs less to 200 lbs more than the control at Arbuckle, though none of these differences were statistically significant. This was especially surprising given 2023/24 was a milder winter than 2022/23, so we would have expected a bigger return from using a dormancy breaker.

This has been a low-yield year across the board for the California walnut industry, and one speculation (which I share) is these low yields are related to last year’s high yields. The hypothesis is trees worked so hard last year they didn’t have as much ‘gas in the tank’ this year, either meaning fewer buds developed last year to form fruit this year or they didn’t have the resources, such as carbohydrate reserves, to support fruit growth this year. This low-resources hypothesis would fit with the increased early fruit drop many growers observed in their Chandlers this May. Our yield results fit in with this idea as well. Treatments with higher yields last year had lower yields this year.

All this together points to the notion that these tools, applied at the timing and rates we used, are likely not suited for every orchard every year. We tried a high rate of Dormex to look for a tipping point of ‘too much,’ and with the data we have, I’m gaining more confidence Dormex at 4% isn’t worth the cost and may actually be too much of a good thing, given we saw budbreak was either similar to or less than when we used Dormex at 2%. In other countries, where they’ve been able to use hydrogen cyanamide for more than a decade on walnut, 1.5% is a more common application rate in mature trees and lower in younger trees. The big swing in yields we saw across both sites this year indicates to me that applying dormancy breakers after optimal chill winters like 2022/23 to an orchard that is already thriving, like the Glenn County site, is unlikely to warrant the cost in the long run. That said, they are likely to still be valuable tools following low- and medium-chill winters, have potential for encouraging additional budbreak in stagnant orchards like Arbuckle and have exciting potential for moving harvest timing for growers with a lot of Chandler acreage.

We’ll keep working in these same orchards for a few more years to gather data after more, different chill winters. You can catch me talking about this in more detail at the California Walnut Conference, January 9 in Yuba City; Tri-County Walnut Day, February 6 in Tulare; Yolo-Solano-Sacramento Walnut Day, March 12 in Woodland; Quad County Walnut Day, March 18 in Modesto or reach out at kjarvisshean@ucanr.edu.