Is planting double-density hazelnut trees, the technique of overplanting a young orchard, a money-making tactic for your orchard? The answer is maybe yes, and maybe no, according to two Willamette Valley farms operated by Dan and JoAnn Keeley, and Jason Perrott and his family.

The decision to double or not varies with each farm’s situation. For example, the Perrott’s and Keeley’s come from different generations and backgrounds: the Keeley’s are on multi-generational farming family land and are nearing retirement age. Perrott still has children at home, owns with his father two other construction-related businesses and began growing hazelnuts in 2012.

The farms have different situations, but the owners share the same goal: They act on predictions they hope will make the most money on the land they have. Dan and Jason share engineering and business backgrounds, reflected in their careful attention to the bottom line. Their experiences and their plans also mirror the variety of decisions tree nut growers must make when considering interplanting.

Theories on the Ground

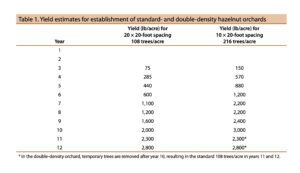

The theory of double density design is this, according to the Oregon State University Extension Service: Plant twice as many trees during the first decade or so of the orchard’s life and for several years increase production until the canopy of too many trees crowds out the sun and reduces production. Although some growers with larger orchards have the equipment to interplant other crops during the orchard’s early growing period, many hazelnut growers are doubling the density of hazelnuts, although often interplanting two different varieties to see which might fare best. Like the standard single density orchard, the double-density orchard has low yield for the first four or five years, then yields nearly double (compared to single density) after the fifth or sixth years. If temporary trees are not removed or hedged after the canopies grow together, production drops after the 12th year or so, and the trees are thinned back to standard density (usually 20 feet by 20 feet).

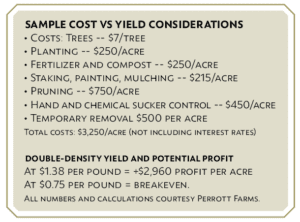

Theoretically, production and profits increase in a few of those years. Expenses to maintain more trees may also rise slightly, but as has happened recently, prices paid for the nuts may fall. Also, as both of the following growers can attest, markets and costs are not the only considerations when deciding whether to plant double-density, risking a current investment in hopes of future profits.

Keeley’s Farm

Dan and JoAnn Keeley farm 100 acres, 40 of which are planted in hazelnuts, a semi-retirement project for the couple who married in 1980. JoAnn’s family settled the land four generations ago, and successive generations farm around the Keeley’s patch, which they bought from her grandfather. While JoAnn and their three children managed the farm, Dan worked as a civil engineer. They began planting hazelnuts in 1992 with an eye to farm a product with lower labor input. Most of the original Casina trees survived damaging storms, root rot and blight until 2003, when they were replaced with blight-resistant trees. Their mature Jefferson variety 20-acre orchard had been double-density, but the final single-density spacing is 20 feet by 20.5 feet.

Buoyed by the success of the first double-density orchard, in 2019 the Keeleys planted 8 more acres to double-density, with McDonald variety interplanted with Yamhills with a 22.5-foot by 26-foot spacing. In 2024 (the fourth year in the ground), the young double-density orchard produced 450 pounds per acre, with the McDonalds out-producing the Yamhills so far. Dan’s previous yields from the Jefferson orchard by the eighth and ninth year were about 4,000 pounds per acre. He predicts the same double-density production for his newer orchards, with plans to remove temporary trees after the ninth year.

But best laid plans, as Robert Burns penned, often go awry. A variety of factors, most of which are out of a grower’s control, can impact orchard plans that, on paper, may look like money in the bank. Weather, disease, market demand, prices paid for nuts and expenses ranging from labor to equipment to tree removal costs and interest rates can infect a spreadsheet with minus signs. If growers keep expenses down and need a small rate of return to offset loans and investments, they are more likely to weather unexpected costs, Dan said. Growers who need to make a lot of money quickly to offset expenses may choose a different course than the Keeley’s long-term plan.

Ever the engineer, Dan has modified a crop estimating database program to track his farm’s crop financial details, helping them make decisions for the future, even though the future may not be entirely predictable. He also uses an unusual planting pattern for his recent orchards that more precisely spaces trees apart.

Risk is a subject dear to Keeley, who has meticulously outlined investment scenarios to reflect how borrowing may influence decisions surrounding double-density. If, as in Keeley’s case, the grower does not have to borrow to plant additional trees, risk and the need for quick profits are reduced. The same applies to those who can borrow at a low interest rate. But as the cost to borrow increases, decisions about double-density plantings begin to hinge on making quicker profits to avoid paying high interest rates.

The couple has low overhead, doing much of the work themselves. Even if prices fall, as they have in the past few years, the Keeley’s plan to make a small profit. As a result, the family added 8 more double-density acres three years ago, PollyOs interplanted with the Yamhill variety. So far, Dan said, the Yamhills are more productive, but he is hoping the PollyOs will “come on strong.”

Perrott’s Farm

Nearly 100 miles up the Willamette Valley, near Coburg along I-5, is Jason Perrott’s 110-acre hazelnut orchard on land originally settled by his grandfather Lloyd, who moved when he was a child to the area from a farm in Alberta, Canada. The urge to farm passed through his father, Ken, but that urge didn’t turn to action until 2012, when the family decided to plant hazelnuts.

Since then, they’ve planted 20 to 30 acres at a time, the youngest acreage three years ago.

“It was a steep learning curve,” Jason said of his family’s return to farming. For the past two generations, the family has built its agricultural drainage company, Ground and Water, and VacX, a utility mapping, equipment and engineering service. Jason grew up working on farms and dairies, working for FarWest Steel after graduating from college with degrees in construction engineering and management. Eventually, he joined his father in business, where he put his education and financial acumen to work. When the land adjacent to his company’s offices came up for sale, the family bought it and returned to their roots in farming.

There were mistakes in the beginning, but Jason said fellow growers have helped see him through. He returned the favor by serving as president of Nut Growers Society of Oregon, where he remains active. He said in the future he would be more precise about chemical application and would pay less attention to the temporary trees. He had assumed double-density would last for 10 or 11 years, but it appears that, using his current methods, the vigorous tree crowns are growing together at eight years and must either be hedged or taken out.

Dealing with the wood from temporary tree removal is an added labor cost for both Keeley and Perrott operations. Both double-density growers are grinding their temporary trees and using the mulch for water, conserving groundcover and natural fertilizer. Perrott also plants fescue and red clover in the alleys between the trees.

Like Keeley, Perrott has an engineer’s eye for numbers, but the two operations have different goals and different expenses. The scale of the Perrott operation reduces the cost per acre for some items, such as tree removal. But both operations over the 8- to 10-year life of a double-density project had approximately the same outcome per acre.

The Perrott’s had been encouraged by good prices in the first year of double-density production and had hoped to see those prices continue as they expanded acreage. But eventually, prices fell to where growing double-density became a breakeven project, both Perrott and Keeley noted.

For the Perrott’s, who manage two other successful businesses in addition to the hazelnuts, the added risk of time and expense of tree removal and double-density crown management play into their decisions about intensive practices. “I would do it again,” Perrott said of double-density planting, “but I reserve my right to change my mind.”

His next plantings will be single density.

For the Keeley’s, whose main project is growing hazelnuts, the additional income from the double-density planting pencils out in their operation. Dan said he plans to continue trying new double-density techniques; his newest orchard, now three years old, is planted with wider spacing that he hopes will allow temporary trees to thrive for 9 to 10 years or longer.

The Perrott’s may try other techniques in addition to double-density planting as the farm continues to expand hazelnut acreage. They’ve recently invested in hedging machinery that would decrease hand pruning, which may allow them to leave double-density trees productive in the ground longer. In their brand-new test kitchen, visitors can taste their products. The Keeleys’ are looking forward to their first harvest of their newest double-density field next year. Both growers are working on measures that reduce labor costs and conserve water.

With each new experiment, Perrott said he learns something new. “It’s intriguing,” he said. “We’re gambling on the future, right? We’ll keep trying new things.”