Correct fertilization of newly planted trees is essential to ensure their success. The goal is to get adequate growth while avoiding weak and spindly primary scaffolds or increasing pruning demands. I was able to research phosphorus fertilization of almonds with Greg Browne (USDA plant pathologist), Brent Holtz (UCCE San Joaquin County) and Jamie Ott (UCCE Tehema, Shasta, Butte and Glenn Counties) for several years across three locations, and we found in general, newly planted almonds grew more when they were given 6 oz P2O5 per tree than trees that received no fertilizer. This was a huge surprise as previous research indicated tree crops in California do not respond to P fertilization unless a leaf tissue analysis indicated they were deficient. We theorized the P fertilizer may help supply the trees with an immobile nutrient before their root systems start to extend extensively and find it on their own.

Following those results, I was curious to see if other newly planted tree species would respond to P fertilization. After receiving funding from the California Pistachio Research Board, I set out to find the answer, at least in pistachios.

The research started at the Westside Research and Extension Center (WREC) in Five Points, Calif. in a Golden Hills orchard on clonal UCB1, planted in April 2023. The rootstock was grafted to the scion in the nursery, so the trees were a year ahead of typical pistachio orchards, where the rootstock is planted and then grafted to the scion later.

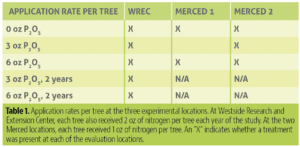

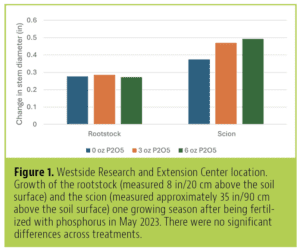

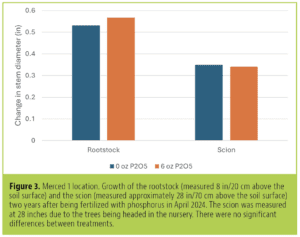

Each tree was fertilized by hand approximately a month after planting. The fertilizer was triple super phosphate and was placed in holes that were dug approximately 1 foot away from the base of the tree. Each tree receiving P fertilizer at the WREC location received 2 oz of nitrogen per tree. I also was curious to see if rate mattered and if fertilizing for two years provided benefits over just one year of fertilization. Treatments are detailed in Table 1. The orchard is being trained to a modified central leader system, so the only pruning is in the dormant period.

My research team and I measured the diameter (caliper) of the tree trunks at planting at the end of 2023 and 2024 to assess the growth of the trees. We measured the growth of the rootstock and scion approximately 8 inches (20 cm) and just over 35 inches (90 cm) above the soil line, respectively. The results from two years of the WREC trial are in Figures 1 and 2.

While it may appear the scion growth improved with P fertilization, there were no significant differences across treatments when subjected to a statistical analysis (Figure 1). Furthermore, any appearance of a trend disappeared after two years of growth (Figure 2). Fertilizing the trees for two years offered no growth benefit over one year of P fertilization, or no fertilization.

The July leaf tissue analysis followed the growth trends at WREC: While regression analysis showed applying P fertilizer increased leaf tissue P values in 2023, any differences disappeared in 2024 (data not shown).

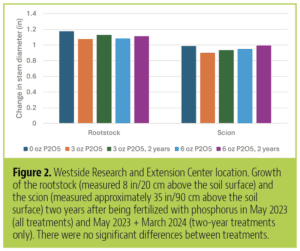

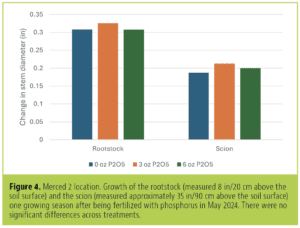

After 2023, I wanted to replicate this trial in commercially managed orchards and located two sites in Merced County. Both were planted in former almond orchards, where the old almond orchards were chipped and incorporated back into the soil. Merced 1 was planted in late February/early March to Lost Hills on UCB1 and Merced 2 was planted in April 2024 to Golden Hills on UCB1. The treatments are outlined in Table 1. Due to space constraints, I opted to reduce the P treatments at each location. At Merced 1, I used the highest rate and examined two years of fertilization (the second year of the trial will be in 2025). At Merced 2, I looked at the two rates of fertilizer, but only one year’s worth of fertilization. The grower of Merced 1 applied seven tons of diary compost were applied per acre in November 2023, delivering about 70 lbs P per acre. While that’s quite a load of P, I was curious to see if the pistachio trees still responded to fertilizer. In the almond P trial, one of the sites had a heavy load of composted chicken manure applied pre-plant and we still found a growth response. There was no compost applied at the Merced 2 location.

Like at the WREC location, fertilization did not impact growth at either Merced location (Figs. 3 and 4). Unlike at the WREC location, there was no impact on July leaf P values.

What is a possible reason pistachios do not seem to respond to P fertilizer, whereas almonds do? Newly planted pistachio trees, even when planted at an ideal time and already grafted to the scion in the nursery, simply do not put on as much growth as first-leaf almonds, so their total demand is likely lower. Additionally, pistachios are known to be phreatophytes, which is a fancy term to describe plants that develop deep root systems to try to exploit water tables. It is possible pistachio root systems expand rapidly after planting and are better able to pick up P. P is immobile in soils and gets to root systems via diffusion (which happens over very small distances) and root interception, so a rapid expansion of root systems could help trees with soil immobile nutrients. I am hoping to investigate pistachio root systems this year to see if my hypothesis is correct.

Thank you to Duarte Nurseries for donating the experimental trees and Jeb Headrick for donating the tree stakes for the WREC location. Thank you to Sam Daud, Brock Boysen and Jimmy Atwal for hosting the fertilization trials. Richard Saldate, Baudelio Perez, Harman Sharma and Gagan Gade, thank you for your work on this trial. This research project was supported by the California Pistachio Research Board, and staffing was partially supported by the California Fertilizer Inspection Advisory Board as well as Conservation Innovation Grant.