Botryosphaeria panicle and shoot blight are caused by a group of Botryosphaeria species that can be devastating to pistachio orchards. Poor understanding of the disease life cycle, how spores spread and the lack of registered fungicides resulted in significant yield losses in the 1980s and 1990s.

Decades of research by Themis Michailides and his associates provided a better understanding of the disease and found a wide range of effective fungicides to control it.

The disease was first discovered in 1984 in the northern Sacramento Valley. Initially, it was thought to be a minor problem since it was only affecting a few orchards, but it was causing significant damage. It was 15 years before the epidemic actually occurred, according to Michailides, a plant pathologist with UC Davis/Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center.

Initially, the pistachio industry supported research on the biology of the disease, but after a couple years, only a few orchards were affected, so the funding was eventually cut.

Michailides, a postdoc at the time, had the freedom to do his own research, so he continued working on the project. He found the pathogen in Fresno County, then San Joaquin and Kern counties, which meant the pathogen was spreading. Severe rains in the spring of 1986 spread the inoculum further.

“The epidemic started in 1997, 1998 and 1999, resulting in a lot of infected orchards throughout California. And that was an alarm for the industry that more research was needed, and then they started funding very generous research to solve the problem as soon as possible,” Michailides said.

Biology

Cankers on branches, fruit clusters and leaves can all be sources of inoculum. Infected tissues left in the orchard produce pycnidia (the fungal structures that produce spores) and can continue to do so for several years after death.

Spores produced by pycnidia are spread by water landing on infected branches, clusters or leaves, which then carry it to new tissues and infect them. Botryosphaeria fungi require temperatures above 50 degrees F to infect plant tissues; however, growth is favored at temperatures between 80 degrees F and 90 degrees F. A few hours of rain or sprinkler irrigation can result in spore release. Spores germinate in water in 1.5 hours and then can infect.

There must be a natural opening in the tree for Botryosphaeria to invade. This could be from the stomata, lenticels, insect or bird damage and infections that occur any time of the year. Botryosphaeria spores will even colonize dead wood.

Research

At first, Michailides thought there was only one species of the fungus, Botryosphaeria dothidea, but as the research continued, he discovered eight different species in the same family that were causing Botryosphaeria panicle and shoot blight.

Research continued over the next decade to develop chemical control, but initially, cultural control was emphasized because there weren’t any fungicides registered except Benlate. Benlate was registered for botrytis blossom blight of pistachio, and research found Benlate (or Topsin in the same class of fungicides) had about a 50% reduction of Botryosphaeria.

“With the cultural practices, we found out in a replicated experiment if we do methodical pruning of infected shoots, I call it selective pruning because we identify the shoots that have cankers, we remove them, and we compared that with regular pruning that the growers do,” Michailides said, adding it was an effective method and reduced the disease by 50% before the registration of fungicides.

Research also discovered that the fungi naturally kill the shoots and the clusters and develop very dense layers of pycnidia on the infected tissues. The infected tissues that die remain on the tree and become the inoculum for the next season. Therefore, growers were advised to prune out infected limbs and clusters to prevent the spread of the disease.

Michailides emphasized cultural practices to growers while working on fungicide trials to find effective chemical applications.

Among the first fungicide treatments found was a strobilurin fungicide called Stratego. It was used in pecans to treat Anthracnose, and it was extremely effective.

“Once we found that it was strobilurin, then various chemical companies requested we try their strobilurins. In fact, we showed that all these materials in the same class of fungicides, strobilurins, were very effective,” Michailides said.

Critical Infection Times

Modifying irrigation practices was used early on to control Botryosphaeria panicle and shoot blight. Full-coverage sprinklers with a high trajectory angle were used for irrigation, and they wet lower branches, leaves and fruit. This created ideal conditions for infections. Reducing the trajectory angle of the sprinklers to 12 degrees and using shorter irrigations reduced disease by preventing the water from hitting trees.

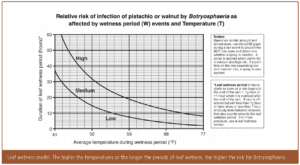

Today, most pistachio orchards are now on microirrigation, but Botryosphaeria panicle and shoot blight can still be an issue with wet springs. For spores to germinate and infect tissues, they need 1.5 hours of rain. Short bursts of rain followed by sunshine pose a low risk for Botryosphaeria infection, but longer periods of rain, especially in the late afternoon or early evening when the leaves can’t dry out afterward, create moderate- to high-risk infection events. Humidity will prolong the length of time leaves remain wet after a rain event.

Latent infections show symptoms in late July, with blighted clusters appearing in August, Michailides said.

“If there is plenty of inoculum, if there is plenty of rain, maybe some late rains in early May that are above normal for that season, the excessive rain will show symptoms on blighted young shoots in pistachios,” Michailides said.

Michailides developed a leaf wetness model to help determine Botryosphaeria risk, but it’s dependent on temperatures favorable for infection (50 degrees F or above) and the length of time leaves remain wet. The higher the temperatures or the longer the periods of leaf wetness, the higher the risk.

It has been shown water-stressed trees are predisposed to infection, and orchards with high humidity can increase infection risk and severity of the disease.

Chemical Treatments

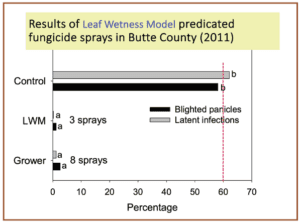

Michailides’ research found chemical treatments and the best timing for application. Some growers have weather stations in the orchard, and they can determine the infection events and apply fungicides.

“The timing for application starts at bloom and ends at the end of July. The best timing for application for Botryosphaeria is the first part of June. If a grower decides to do one spray, that’s the spray to do, the first part of June,” Michailides said. The number of spray applications depends on the level of infection according to the leaf wetness model.

Several materials are currently registered, not just strobilurins. “We also have combinations, pre-mixtures of strobilurins with carboxamide fungicides, and all of these are very effective, and they rate a grade five. Five is excellent control,” Michailides said.

With pruning and chemical treatment, growers can achieve a manageable level of control, and if they continue this regimen for several years, they can eventually eliminate the disease, provided the weather cooperates, Michailides said.