Listen to the audio version of this article. (Generated by A.I.)

October. The season isn’t over with harvests finishing up and plenty of work to prep for next year. Key activities include harvest, postharvest irrigation, fall nutrition programs, cover crop planting, year-end orchard scouting and pruning.

Water

Good fall irrigation practices support trees now and next year. With leaves still on the trees, adequate irrigation is needed to support photosynthesis (water + CO2 + sunlight = sugar + oxygen) to power current plant activities and provide feedstock for winter storage. Daily orchard water use will drop through October as days get shorter and cooler, but that water is key to good orchard health. Mild water stress (-10 to -14 bars using the pressure chamber) is OK after harvest according to UC researchers. These targets should be -4 to -6 bars below baseline given expected high temperatures in the 70s to 80s. See UC ANR publication on using the pressure chamber in the reference section at the end of the column. Keeping up with fall irrigation is key to preparing the orchard for next year.

Lack of fall irrigation can reduce tree size in young orchards, especially in sandy or gravelly soils with low water-holding capacity. Keeping up with fall irrigation could be especially important in certain self-fertile varieties on standard-sized rootstock where high nut set in the second and third leaf can slow tree growth, eventually keeping the trees from filling their space and reducing cumulative yield over time. So a key to long-term high production in these variety/rootstock combinations is strong vegetative growth early in the life of the orchard, and part of that strong growth is keeping up with late-season irrigation.

Nutrition

In these difficult economic times in California orchards, getting the best results from fertilizer dollars is important to staying in business. A prime example of this is boron nutrition in almond. A fall B spray (0.4 to 0.6 pounds B per acre) increased almond yield in a well-managed (but low-B-status) orchard by as much as 300 pounds per acre in UC research. Increasing nut yield from 2,100 pounds per acre to 2,400 pounds per acre is the difference between netting -$200 per acre or +$300 per acre (based on total cash costs per acre and $2-per-pound nut price in Table 5, 2024 UC Davis Cost of Producing Almonds in the Sacramento Valley.

B nutrition should be front and center in fall nutrition in almond orchards, especially in the Sacramento Valley. B is relatively inexpensive, requires low fertilizer rates, and wet winters produce low soil B conditions, leaching soil B and increasing availability of surface water (with very low B content) for irrigation. Where harvest hull analysis shows low to moderate B (<120 parts per million), there is no better return on investment than a fall B spray (adding B foliar fertilizer to a pink-bud bloom spray produces the same yield increase as a fall spray in UC research.)

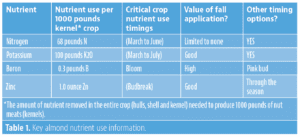

Talk with your CCA and review lab reports for harvest hull B analysis before deciding on materials and rates for a B program. If hull B levels are deficient (<80 parts per million), a fall B spray and soil-applied B (fall or spring) may be needed to improve B status of the orchard. David Doll (thealmonddoctor.com) recommends 2 to 4 pounds of actual B per acre (10 to 20 pounds Solubor per acre) as an annual soil-applied B fertilizer rate. In orchards with low B status, don’t expect a fall (or spring) B spray to change hull B at harvest as a good crop will remove the equivalent amount of B (Table 1).

Finally, approaching a B fertility program with caution is suggested. B is both an essential nutrient and a toxic element in plants. High rates of B fertilizer can reduce yield, and full bloom B foliar fertilizer risks reducing nut set. If hull B levels are low, add some B and check hulls next year, then adjust practices accordingly. Checking hull B levels at harvest every year is the best way to keep an orchard between deficiency and toxicity.

The most commonly deficient essential mineral nutrients for almond (and many other tree crops in California) are nitrogen, potassium, zinc and sometimes B. N, K, Zn and/or B deficiency reduce almond yield. These nutrients have differing critical plant use timings and different critical fertilization timings to increase or maintain yield the following year (Table 1).

Zn is also important to early season (bud break and bloom) almond performance. Zn -deficient almonds bloom later than Zn-sufficient trees and can reduce yield. Unlike B, Zn doesn’t accumulate in the hulls, so Zn fertilizer applications can be made through the growing season and remain in the tree for use at bud break. A single foliar Zn application is generally considered sufficient and cost-effective. An October application of low (5 pounds per acre zinc sulfate) has been shown to provide as much Zn into young peach trees as high rates (10+ pounds per acre zinc sulfate) in November, and this result should be similar in almond. Zinc sulfate (36%) can be tank mixed with B in fall sprays. Polyborate (e.g., Solubor) and zinc sulfate mix best when tank pH is acidified (pH = 5). Boric acid products and zinc sulfate do not require pH adjustment. A higher rate of zinc sulfate can drop leaves when applied later in the fall once relative humidity levels are up.

What about K and N application in the fall? K is an important component of nut growth and so must be available to the plant in the spring through midsummer. Fall application of dry, coarse K fertilizer to the soil as a band or narrow (6- to 8-foot wide) broadcast is an effective practice as the K+ cation can be held in the soil and available for use by the plant in the spring. Soils with lower cation exchange capacity (<10 milliequivalents per liter soil) can lose some fall-applied K through leaching with winter rains; a recent study measured 15% soil K loss from a sandy loam soil. Growers must balance the convenience of fall maintenance rate of soil-applied K with increased logistical issues associated with spring K applications, including opportunity costs of labor spent applying K fertilizer in a busy time when other tasks are pressing.

N is a critical nutrient for successful almond production, but fall-applied soil N fertilizer did not increase yield the following year in a multiyear study where summer leaf N levels were adequate or higher. If summer leaf N levels are just above adequate and a little extra N to the trees is wanted, a low rate of foliar N (5 to 10 pounds low-biuret urea per acre) in the fall can help increase B uptake from foliar B fertilizer and provide some extra N to the buds ahead of leaf drop.

Pest/Orchard Review

Fall is a good time to walk orchards looking for shaker damage and trunk/scaffold disease. Monitoring bark health ahead of winter rain makes it easier to see diseased bark as rainwater can dissolve gum on bark, making the canker much less obvious.

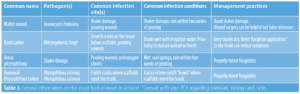

Canker management differs between pathogens. Effective canker management requires accurate disease identification. Ceratocystis cankers are characterized by gumming on the canker edges, which develop at bark injury sites such as shaker damage or pruning wounds. Aboveground Phytophthora infections fall into two general categories. Annual aerial Phytophthora syringae infections associated with pruning wounds or undamaged shoots display bright red to amber gum balls, while Phytophthora citricola and Phytophthora catorum are usually associated with aggressive infections arising from cracks where scaffolds meet the trunk. Botryosphaeria infections (band canker) are usually limited to the trunk below the scaffolds where growth cracks are exposed to irrigation water and often near mature walnuts.

If shaker damage and/or active Ceratocystis cankers are found, map the damaged trees and plan to return in the winter when insects that carry spores of this disease and the disease itself are less active to cut out the disease canker by hand.

Talk with your PCA about Phytophthora management options going into the fall, especially in orchards where early rains fell when nuts were still in the trees.

Rust was a problem this year in some Sacramento Valley orchards. Rust inoculum overwinters on lingering leaves, so a side benefit of a high rate of zinc sulfate foliar fertilization (20 to 40 pounds material per acre) is defoliation, which reduces inoculum going into next spring.

When scouting the orchard for trunk damage or disease, noting the weed species in the orchard and their locations helps plan for future management.

Pruning

Healthy young orchards are critical to the economic future of farming operations. Scaffold selection (pruning) helps trees hold large crops without breaking. However, pruning wound infections can be devastating to orchard health.

To limit pruning wound infections, avoid pruning with rain in the forecast. This is especially true for scaffold selection in newly planted (2025) orchards; the cuts are relatively big and close to the trunk. Wind, pickup machine blowers and insects move bark canker disease spores to pruning wounds. Rainwater wets the cuts and promotes infection.

So when do you prune? This is a tough call, but a good answer might be anytime you want as long as cuts are then treated with fungicide. Treating pruning cuts with fungicide can help reduce infections if rain follows pruning. Treating pruning wounds with thiophanate-methyl (Topsin-M®, etc.) immediately following pruning delivered the most consistent canker management in UC research. Making big pruning cuts heading into the rainy season (without treating the cuts) is like leaving the front door open when headed out for the weekend. You never know what you might come home to. Always consult with your PCA regarding materials, rates and timing for pesticide application.

Soil Cover

Cover crops and mulch help slow rainwater runoff and improve infiltration. Cover crops should be planted by the end of October for best results. Almond shell or shell/hull mixes provide K to the soil if water (rain or irrigation) wets the material.

Best wishes to all for a less busy fall and solid tree nut markets.

Resources

sacvalleyorchards.com: Loads of great articles and info (weekly ET, nutrition, meetings, pictures, etc.) This is a site developed and maintained by UCCE orchard advisors in the Sacramento Valley.

Trunk & Soil Diseases in Almond: sacvalleyorchards.com/almonds/trunk-soil-diseases/

ipm.ucanr.edu/almonds and ucipm.ucanr.edu/walnuts: Great information on pests with photos

Specific topics/titles:

• Using the pressure chamber for nuts and prunes: anrcatalog.ucanr.edu/Details.aspx?itemNo=8503#FullDescription

• Ceratocystis in almond: ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/almond/ceratocystis-canker

• Aerial Phytophthora: sacvalleyorchards.com/almonds/trunk-soil-diseases/aerial-phytophthora-outbreaks-in-wet-years

• Pruning wound protection: sacvalleyorchards.com/almonds/trunk-soil-diseases/pruning-wound-protection

• Perennial phytophthora: sjvtandv.com/blog/resurgence-of-perennial-phytophthora-canker-disease-of-almonds

• Fall weed survey: ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/almond/survey-weedspostharvest

• Fungicide efficacy and timing (at the bottom of the page): ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/