Listen to the audio version of this article. (Generated by A.I.)

James Chinchiolo of Chinchiolo Farming Co. comes from a long line of growers, but they didn’t always grow tree nuts. His ancestors immigrated to Boston from Sicily, where they started a fruit-dealing business importing grapes from California for winemakers. As part of that venture, one branch of the Chinchiolo family decided to head to California to grow their own winegrapes to supply the family trade business in Boston, until another kind of family got involved.

Chinchiolo says his grandfather tells the story of their switch to other crops like this: “At some point around the 1940s, a really well-dressed Italian man basically told us that we were done in the wine grape industry, and that propelled us into needing to completely get out of the grape industry, diversifying into other things like walnuts and cherries.”

Chinchiolo Farming has been focused on cherries and walnuts ever since. Despite leaving the farm after college to work in the business world, Chinchiolo always knew he wanted to return. Taking the new perspective he had gained from working elsewhere, he took over day-to-day operations of the farm in 2018.

We asked Chinchiolo to share his story and his thoughts on the current state of the tree nut industry.

Q. How did your family get its start in growing tree nuts?

My family came over from Sicily through Ellis Island and began as fruit dealers in Boston. Everything that I know of our family history is that we began importing grapes from California for wine making. Some of the family moved to California and started growing grapes, exporting them to the other side of the family into the Boston area for wine making. Over time, we expanded and diversified into other commodities. My great-grandfather was first generation, and I’m fourth generation in farming.

Q. How did you get into the family business?

I kind of always knew that I wanted to farm. There was a time when I was about 6 years old when I learned how to drive one of our old tractors, and I just remember that every time my dad would say, ‘Hey, I’m going to be going to the ranch tomorrow. Do you want to join?’ I always wanted to be a part of coming out here.

There was a certain something about the farmers out where we farm, where everything’s done by handshake, and your word is your word. That was something I was attracted to.

I graduated high school, went to University of the Pacific, and my dad during the process of growing up and around the time when I started college said, ‘If you ever do want to come back into the family farming business, you really need to get a job outside of farming first.’ What he found was it was really valuable to go out and get his own job and then come back because he was able to bring a whole bunch of additional skills and just a real sense of what the outside world is like.

I think there’s a certain safety, if you will, within a family business. It’s hard to really know the value of a family business without stepping outside of it. I ended up running a company for these fellows out of Colorado, landslide and rockfall mitigation. I built that from nothing all the way up to about a $12 million company over the course of 10 years. That company wanted to become bigger and started to become more corporatized.

About that time, my dad was saying, ‘Hey, I think I’m going to lease the ground out.’ And I said, ‘Whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa. Maybe you don’t understand, but I want to come back into farming.’ Then I got back into the farming business and took over for my dad. He’s still very involved, but as far as the day-to-day operations, I take care of that.

Q. How do you think farming has evolved over your involvement, from when you were a kid to now?

I think so much of it is how some of the bigger companies are becoming bigger, and some of the smaller farming operations are being bought by these bigger companies. A lot of it just makes sense. I don’t think it’s necessarily a bad thing. I think it’s just an evolution because a lot of the children of the farmers, they just didn’t have the same interest that I did to come back to farming.

I think a lot of that has to do with economics. There’s just not a lot of available money in farming, especially when it’s just maybe a couple-hundred-acre operation.

Q. What kind of tech advancements have you seen?

We are definitely seeing a lot more precision. What I mean by that is I think a lot of the tools and techniques that we used in the past were based on feel, and now so much, especially with respect to applying beneficial fertilizers, is monitored very, very closely. In our operation, flow meters are used on spraying equipment. We talk about miles per hour in the field down to the tenth of a mile in terms of ground speed.

And then, I might be just seeing this through my own lens, but I’m also seeing a little bit of a going backward in time. There’s the saying that ‘the ancients stole our best ideas,’ and I think that so much of what some of us fourth- and fifth-generation farmers are starting to see is that a lot of the tools and techniques that our forefathers used are really detrimental to the soil health.

I’m seeing a lot of focus back on some of the more restorative or regenerative parts of farming that people like my great-grandfather knew. That’s how he farmed. He didn’t farm with a lot of the chemical farming tools that we have now. So I see a fair amount of farmers starting to go backward, trying to figure out how their great-grandfathers farmed, which is a challenge because we still need to be competitive in the financial landscape that we’re in right now while still trying to achieve more of a regenerative focus.

Q. Talk a little bit about trying to reclaim ground that hasn’t had the right inputs in past generations.

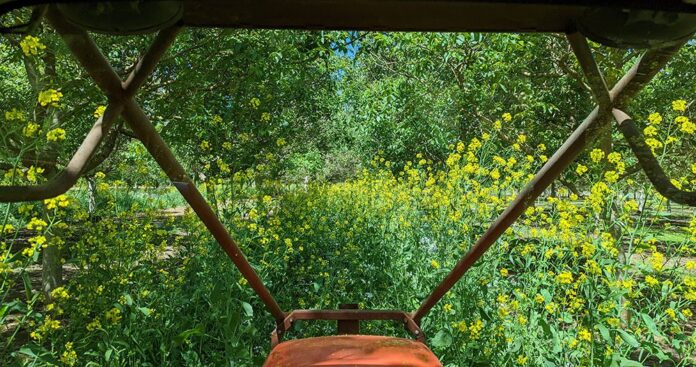

One of the big things that’s important is just the value of keeping roots alive. What I mean by that is there’s been so much focus, at least what I was taught, on keeping one’s orchard floor really clean for harvest. Now, I see the value of keeping the weeds going because it seems to help. Those weeds ultimately provide the sugars to the microbes in the ground, and those microbes ultimately are kind of symbiotically improving the soil as well.

There’s this huge microbial army that I want to keep alive and healthy within the soil. And the minute that I eradicate the weeds or anything that’s living on the orchard floor, I immediately starve this herd of microbes. I’ve just been trying to keep living roots as much as reasonably possible.

And then there’s cover cropping. I’m a big, big advocate of cover cropping. With the cover crop, as opposed to mowing it, I’ve bought a machine to crimp it, to basically just lay it over once it gets to the point when it needs to be terminated. Laying that over adds a whole bunch of potential food for the microbes and keeps the orchard floor shaded and cool.

Q. What are the things that keep you up at night about growing tree nuts?

The financial side of it right now. I’d sure like to be in a position where there was an abundance of money, so that I could continue to grow whether it be in acreage or in overall equipment. We’re starting to see quite a bit of our equipment start to age, and it’s built to last, but at some point, we’re going to run into some issues here.

The other is just the sense of not knowing if what I’m training my guys for is going to last. Are my guys going to stick around? Some of that dovetails with the financial side. I want to pay my guys more. I can’t. And my fear is that I’m going to get them all trained up, and they’re going to know all the ins and outs of farming like I do, and then once they have that value, they’ll be attracted to another outfit or another industry. And all of a sudden it’s, “Darn, now I have to start all over again.”

Q. Can you talk a little bit about the water situation?

I’m in the camp that the water is not the issue. I’m in the camp that it’s a matter of mindset, and the mindset difference between abundance mentality and scarcity mentality. That’s my personal opinion. That’s also based on just observing what’s going on.

Plenty of water is available in California. We’re just not managing it. I think the way in which we manage water is based on some sense that we as humans can’t leverage it or it’s bad for us to leverage that resource, especially surface water. I think that’s to the detriment of the groundwater resources that we have.

Q. You talked about people in your generation leaving the family farm because of finances. What do you think the answer is to keep family farms alive?

That’s a really difficult one. I think there are many aspects of it. I think that farming as a whole is a very rugged industry, and I think this is a hard question because I think if it were a little bit softer of an industry, if we spent a little bit more time taking care of ourselves as opposed to the trees, it would help.

What I mean by that is just setting the environment up a little bit better in these farming operations to attract people, including ourselves. I think that would be helpful.

“I want to pay my guys more. I can’t. And my fear is that I’m going to get them all trained up… and then they’ll be attracted to another outfit or another industry.”

– James Chinchiolo, grower, on labor and retention challenges

Q. What specifically would you change to make that environment better?

I think about our own situation, and I have two boys who are 18 and 20. What I’m trying to do is develop a business that allows for a role for them that isn’t my role. Perhaps they end up taking over a marketing role, a role that I developed for them.

I think that’s personally a way to continue the family business, and that’s what I’ve observed locally here. Those who tend to attract their family back in, it’s because those businesses are growing and they’re creating roles that are like other roles and other businesses outside of agriculture, where it’s not just the rugged farming piece. They can go to college and get a degree and apply their degree in the farming business rather than just farming 200 acres, for example.

Q. You sell walnuts direct to consumers. Can you talk a little bit about how that came about?

We actually started with our cherries. We opened up one of our orchards for people to come in and pick cherries directly off the tree, which is as direct to consumer as you can get.

Then in 2020, we didn’t know whether or not our cherries were going to be able to ship because of COVID. So I figured, “You know what? I’m going to use the database that I have for my U-Pick and just say, Hey, I’ll ship cherries to you.” And from that, I got a lot of really positive responses saying, “Hey, we can’t get these cherries anywhere else.”

Then I started the walnuts in a small way. I told my cherry customers that, “Hey, click this button if you have interest in receiving information about our walnuts.” And out of 10,000 people, about 300 people said yes. That’s not that many, but I got the same response as the cherries: “We can’t get these nuts anywhere. These are so great. They’re actually fresh.”

Based on those positive comments, we basically tripled our business, our gross revenue last year for the 2024 crop. We’ll see what happens this year, but we’re just going to continue to expand upon that.

It’s just very basic: in-shell walnuts and shelled. No flavoring, no nothing. Just here’s the best walnuts we can provide you.

Q. If you were going to give advice to someone getting into nut farming today, what would you tell them?

I would definitely say make sure that you’re working with economies of scale. I don’t think there’s any sense in trying to come in with less than a couple hundred acres.

I would also say be very aware of what the soil was used for in the past. Know what was farmed on it in the past, if anything. From what I’ve observed, those who buy row crop ground and put walnuts in, those trees just jump out of the ground and are super healthy.