Growers developing a new almond orchard or replanting another make many important decisions in preparation for planting the new trees (i.e., decisions from soil preparation and irrigation design to rootstock and variety selections). The sole purpose of such decisions is to have a productive orchard that will last for approximately 22 to 25 years or more. However, diseases affecting the root system as well as the main trunk can cause significant tree losses or significantly reduce tree growth and productivity throughout the life of the orchard and may shorten the lifespan of an orchard.

Among the important diseases that affect young orchards and cause main trunk cankers is band canker. This disease mainly affects young almond orchards and trees between the fourth and sixth leaf. However, in recent years it has been reported also in orchards from first through third leaf as well. While this disease is not new to California and had mainly been reported from orchards in the Sacramento Valley and in the northern parts of the San Joaquin Valley, in recent years it is being reported more and more throughout the Central Valley as far as Kern County in the south.

Members of the Botryosphaeriaceae family, such as Botryosphaeria dothidea, Lasiodiplodia spp. and Neofusicoccum spp., cause band canker on almond trees and are spread throughout California including in Kern County. Furthermore, many fungal pathogens of this family can also cause important trunk and scaffold diseases on many fruit and nut trees including almonds.

Disease Symptoms, Signs and Biology

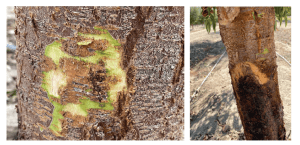

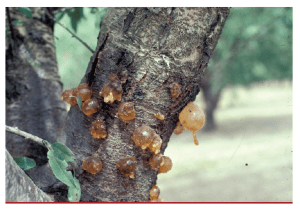

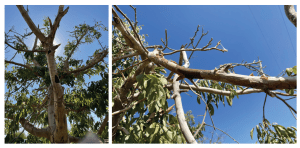

Band canker symptoms appear on affected almond trees as an amber-color gumming exuding from affected parts usually arranged in a horizontal band pattern around the trunk (Figure 1). Removing the bark will reveal brown discolored inner bark and xylem tissues (canker) at the affected area. Cankers may develop further around or up and down the main trunk at the infection site (Figure 2) and sometimes around the base of main scaffolds (Figure 3). Severe cases of the disease may cause tree decline and death.

To diagnose band canker in general, we prefer to look for the visible different identifying fungal parts called disease signs. In many diseases, signs will help us diagnose the causal agent and the disease. Signs of band canker may include the presence of a distinguished fungal fruiting body on the bark called pycnidia and/or pseudothecia. Those structures can be observed in the orchard using a lens or in the lab under a dissecting scope. Fungal fruiting bodies, called pycnidia, will usually hold asexual fungal spores called conidia which are considered a source of inoculum inside the orchard.

Previous research had also provided significant information on the main sources of inoculum for this disease which is usually affected by trees and plants in close proximity or surrounding the orchard such as plants and trees in riparian areas along canals and streams, or, for example, a walnut orchard with trees affected by Bot canker and blight or a pistachio orchard affected by Botryosphaeria panicle and shoot blight diseases next to an almond orchard. Usually, the disease incidence in such cases will be the highest in almond trees near the main source of inoculum, and incidence will decrease as we move further away from the inoculum source.

Infections of band canker mainly take place through wounds and growth cracks in the bark on young trees. The fungus kills the bark and cambium layer, and the affected area becomes sunken and frequently girdles the limb or may girdle the main trunk.

For many members of the Botryosphaeriaceae family, rain events in winter and early spring play a major role in the release and spread of conidia and ascospores from fungal fruiting bodies (pycnidia and pseudothecia) to the susceptible host tissue and initiate infection. However, for the infection to develop into a disease, favorable environmental conditions should be present, and band cankers become active during warm weather in the spring and summer in the growing season; these cankers usually do not reactivate the next growing season.

Recent research on band canker affecting first- and second-year almond orchards had focused on another theory. The theory developed because many of the affected trees are spread randomly throughout the orchard, and not in the close proximity to a source of inoculum, or there might not be a known source of inoculum in close proximity to the affected orchards. That theory is focused on disease development from latent infections that took place before planting, and then disease was expressed in the orchard once the host and conducive environmental conditions became favorable for disease development. To learn more about this research and new developments from this research, an article was published on the Almond Board of California website (almonds.com/almond-industry/industry-news/new-developments-managing-band-canker-almonds).

Case from Kern County

Recently, a farm call to a two-year-old almond orchard identified the problem in the field as putative band canker. Disease symptoms on almond trees initially appeared as gumming on the lower part of the trunk with band appearance around the base of the trunk similar to what we observe in band canker. Removing the bark at the symptomatic area revealed visible canker underneath. We could not see or observe any fungal fruiting body or any signs of the disease on inspected trees in this orchard.

While we may not always see the signs of band canker caused by the different Botryosphaeriaceae, the best way to confirm the causal agent is by taking a sample for diagnosis at a plant pathology laboratory to isolate and identify the pathogen. Isolations from the affected tissue from different trees consistently resulted in the diagnosis of the pathogen Neoscytalidium dimidiatum as the causal agent. This is the first time that N. dimitiatum has been implicated as a causal agent of band canker. This pathogen is also known to cause shoot and scaffold cankers, and even lately has been implicated in causing hull rot in almond orchards in Madera and Kern counties.

Disease epidemiology was a classic case of band canker. Going back to the affected orchard, we observed that the almond orchard was planted across from an older walnut orchard that showed symptoms of branch wilt and scaffold dieback upon inspection. The symptoms and the signs observed in the walnut orchard confirmed N. dimidiatum causing the dieback on the walnut trees (Figure 4).

Besides the presence of cankers, the distinctive arthroconidia were apparent as a black dust underneath the bark. This is a classical epidemiological case where the infected walnut orchard was the main source of N. dimidiatum spore inoculum, and most likely the minute black spores were blown into the almond orchard from the infected walnut trees, landed in growth fissures on the main trunk and developed infections resulting in band canker.

Previous work had shown that N. dimidiatum thrives in warm temperatures, and laboratory experiments show that this fungus’ highest growth rate in culture was at 95 degrees F. We are now monitoring the trees to see if the cankers continue to expand or whether any formation of the arthroconidia under the almond bark could serve as a source of inoculum to other healthy trees in the orchard.

It is worth noting that not every symptom such as amber-colored gum exuding from the base of the trunk resembling band canker is caused by this disease. It has been reported before that gumming similar to band canker can be caused by abiotic factors, such as herbicide spray damage on tree trunks (Figure 5). As part of any disease or a problem in any orchard, it is important to look at the whole picture and at the pattern of affected trees in the orchard as well as the place of the symptoms. For example, if almost every single tree in the row is showing uniform gumming at the same level above the soil surface on both sides with dead tissue underneath the bark, and no evidence of canker expansion, then most likely we are dealing with abiotic factors such as chemical injury. Once in doubt, the best way to confirm the presence of a disease is by taking a sample to isolate the putative causal agent if present.

Management Practices

An important aspect of managing band canker depends on understanding the main source of inoculum. If the source is diseased plants adjacent to the young almond orchard, removing the diseased host (source) or diseased parts is very important to reduce the primary inoculum and eliminate the source. In the previous example from Kern County, the walnut orchard which is believed to be the main source of the pathogen was removed mainly because if its old age and declining trees. This step eliminated the source of inoculum and any future chance for the continuous presence of N. dimidiatum spores moving from the infected walnut trees into the almond orchard. Since then, there were no more reports of new infections expanding to new trees in that orchard. Moreover, it is also important to remove rapidly declining and dying almond trees or infected branches since they become themselves a source of the inoculum inside the orchard.

An additional aspect of disease management is minimizing and avoiding tree stress and trunk injuries, and follow proper horticultural practices to minimize growth cracks, and keep tree trunks dry by installing splitters in the microsprinklers so that the chance of initiating infections through injuries to the main trunk will be diminished.

References

Michailides, T. J. New Developments in Managing Band Canker in Almonds. 2021. Almond Board of California (almonds.com/almond-industry/industry-news/new-developments-managing-band-canker-almonds). Last accessed 01/01/2023.

Luo, Y., Lichtemberg, P. S. F., Niederholzer, F. J. A., Lightle, D. M., Felts, D. G., and Michailides, T. J. 2019. Understanding the Process of Latent Infection of Canker-Causing Pathogens in Stone Fruit and Nut Crops in California. Plant Disease 103: 2374-2384.

Inderbitzin, P., Bostock, R. M., Trouillas, F. P., and Michailides, T. J. 2010. A Six Locus Phylogeny Reveals High Species Diversity in Botryosphaeriaceae from California almond. Mycologia 102: 1350–1368.

Michailides, T., Trouillas, F., Yaghmour, M., and Viveros, M. 2021. New Foes of Almonds at Hull Split Stage. West Coast Nut. August pp. 38-43.