The plethora of tree nut acres in California agriculture is increasing disease pressure, both from soilborne pathogens that survive from one planting to the next and from foliar pathogens spreading within and between orchards.

And with new restrictions looming on fumigation and more acres being planted in dense settings, the danger is things will only get worse, according to University of California plant pathologists.

One issue of concern, according to UC plant pathologists, is that growers are planting orchards back to back without breaking disease cycles.

“Historically, the guidelines have always been to fumigate or to rotate to a different crop for a year or two, with rotation being the cheaper way to go,” said Jim Adaskaveg, professor and plant pathologist at UC Riverside. “But, obviously, the rotational crop probably doesn’t make the same amount of money, so the grower will usually want to plant back in almond or walnut or pistachio as soon as possible just because they know that it takes three to five years before they start getting income back.”

“The tree crops are very valuable,” added UC Davis Plant Pathologist Themis Michailides, “and because it takes three, four or five years to come into production, growers are anxious to plant as soon as possible to gain a couple of years.”

The economics of planting back to back make sense, the pathologists said, but rushing into the next production cycle carries risks that can hamper production for years to come.

“Especially with walnuts and even with almonds, you can have replant issues because they have toxic materials in the degradation process of the older root systems,” Adaskaveg said. “A lot of it depends on how well you remove the old root systems. But you can have pathogens build up, nematodes build up in the soil, and that means that if you don’t do a rotation and just go right back into almond or go right back into walnut, you’ll potentially have a buildup of soilborne inoculum in that situation. And with all the restrictions on fumigation taking effect, people have to think about what they’re going to do in the sense of disease management.

“There are post-plant nematicides that can be used,” Adaskaveg added. “There are post-plant Phytophthora fungicides that can be applied. And so, there are options for the growers. But there is going to be a buildup of inoculum if these diseases aren’t managed.”

Intercropping

In the absence of fallowing land, many growers are intercropping with grains or vegetables to help minimize disease pressure from soilborne pathogens while optimizing use of farm acres. The practice often involves offsetting tree rows from the previous orchard and planting an intercrop in the rows where the trees once were. The practice mitigates some risk by moving tree rows to where problems with nematodes are less intense, Adaskaveg said, and the intercrop can help reduce nematode pressure.

A crop like mustard greens can be particularly beneficial in these systems, Adaskaveg said. “The mustard greens will do a better job for that [than grains], and you only need to do that probably for a year, and then you can get back into getting ready for production in the second or third leaf of that orchard.”

But mustard greens can potentially bring in other pathogens, like Verticillium, he said. “If you do intercrop vegetable crops, you have to be very careful in what intercropping you are going to do,” Adaskaveg said.

“Obviously grain crops are less likely to be bringing in these other pathogens of tree crops,” he added. And, while not as effective in reducing nematode populations as mustard greens, grain crops nevertheless can benefit soils and lower pest pressure.

Ideally, the pathologists said, the best option is to fallow ground or raise a cover crop for a year before replanting an orchard. Michailides, who is based at the Kearney Ag Research and Extension Center, said researchers at the center raise oats or an oat-vetch combination for one year between orchard plantings to reduce soilborne pathogens.

But researchers aren’t worried about generating income off the acres, he said, and so are more likely to take a year off. “The growers are probably anxious to get something back in the ground and make some money,” Michailides said.

“These are choices growers have to make,” Adaskaveg said.

Foliar Diseases

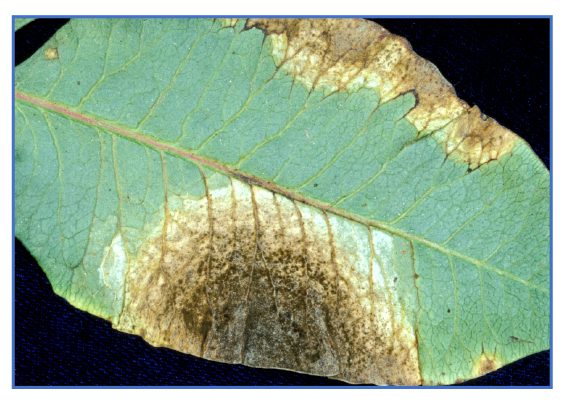

One issue that has emerged from the continued expansion of tree nut acres in California is an increase in foliar diseases, Michailides said, and much of that can be explained by a subsequent increase in relative humidity.

To illustrate the situation, Michailides noted that when he started with the University of California system in 1979, approximately 30,000 acres were planted to pistachios in California. Today, close to 450,000 acres of pistachio are growing in California. Almond acres also increased at a dramatic rate in that time span.

“And all of these acres have to be irrigated,” Michailides said, “and now you have large acreages of pistachios and almonds next to one another and it is almost like a continuous irrigated land, and that contributes to a tremendous increase in relative humidity. And now we have denser plantings, which also contribute to the increase of the relative humidity.”

Diseases that years ago were not a problem now are, Michailides said.

“Now Alternaria, which depends on very high relative humidity, has become a very serious and a very difficult-to-control disease,” Michailides said. “I would say it’s maybe a 30% increase in Alternaria compared to what we once had.”

Growers have several options for controlling Alternaria leaf spot in almonds and Alternaria late blight in pistachios and can take preventive steps to minimize their presence. In some cases, however, disease prevention is taken out of a grower’s hands.

Take for example when a walnut orchard with an impact sprinkler system is adjacent to an almond orchard.

“If your land is adjacent to someone who is using different practices for their orchard, so if one guy has microsprinklers or drip and the other guy has an impact sprinkler, and it could be walnut next to almond or almond adjacent to almond, then those adjacent rows are going to be affected,” Adaskaveg said.

“In those cases, we see edge effects, where the humidity is higher and those first two or three rows next to a walnut orchard have more disease because the microclimate effects from the walnut is affecting almonds,” Adaskaveg said. “And so, we see Alternaria leaf spot being more of a problem in that situation.

“Even though Alternaria is not a big deal in walnuts, because they are watering, it can affect the microclimate and the adjacent orchard gets more Alternaria leaf spot on the edge rows,” he said.

Michailides added even in those cases, growers can help minimize the chance of a disease spreading from one orchard to another through irrigation practices.

“Because it is airborne, Alternaria can spread from one orchard to another,” he said. “However, if an orchard is very dry due to the way the grower irrigates and it’s next to an orchard with Alternaria, I think the chances for the Alternaria to develop in the adjacent orchard would be minimal.”

To illustrate this, Michailides noted that in one study, researchers were able to show a 50% reduction in disease incidence between an orchard using flood irrigation and one using subsurface irrigation. “It changed not only the relative humidity, but also the temperature was affected,” Michailides said. “It was two to three degrees higher in the subsurface irrigation blocks.”

Between good irrigation management, intercropping, fallowing when possible, scouting and chemical controls, growers should be able to stay ahead of diseases in orchard nut crops, researchers said. But it appears to be getting more difficult.