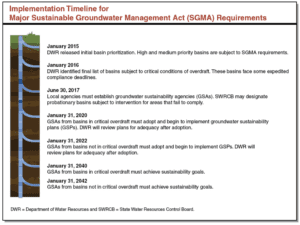

In California, where water quality and quantity issues vary significantly, getting a groundwater sustainability plan (GSP) approved is often a lengthy and challenging process for the state’s groundwater sustainability agencies (GSAs), which represent diverse stakeholders from both rural and urban areas. As of Jan. 31, 2024, the Department of Water Resources (DWR) reported that out of the more than 260 GSAs formed in over 140 basins, only 71 had approved GSPs. Additionally, 13 basins were found to have incomplete plans, and six were deemed inadequate. This review covered all basins that were required to submit plans by Jan. 31, 2022.

As GSAs continue to work on their groundwater sustainability plans (GSPs) to comply with the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), the success stories of those who have achieved approval might serve as beacons of hope amid what seems like a monumental task. One such success story is the Yolo Subbasin Groundwater Agency (YSGA).

According to YSGA Executive Officer Kristin Sicke, YSGA benefited from an already well-established forum of water managers and the previously established Water Resources Association of Yolo County, which provided a strong starting point for developing and implementing their GSP.

“It was this perfect foundation for us to go and create a groundwater sustainability agency,” Sicke said.

From there, it was a matter of asking others in the county who could also be GSAs to join them, creating one GSA to cover the county. Sicke said once they received the ‘OK’ from DWR to consolidate the four subbasins in Yolo County, they were able to create YSGA.

“We felt that was going to position us in the best way to essentially leverage all the historical, county wide water planning that had been occurring, and really create economies of scale,” she said.

As they formed YSGA, Sicke said part of getting rural entities on board was to focus on how they would serve as the reporting regulatory compliance mechanism but still maintain smaller management areas in the subbasin that would focus on the unique hydrogeology of an area.

Emphasizing efficiency at the top level for state reporting, while ensuring local control for smaller units, Sicke said given the county’s vast size and diverse interests, some stakeholders were concerned their water rights could be encroached upon by other areas of the county, but their agreement for local control would address those concerns.

Working Together

While agriculture is a large part of Yolo County’s economy, Sicke said there is still tension between the ag and urban sector and the differing needs. With the goal of maintaining a cohesive team to create economies of scale and comply with legislation, she said they aimed to present a united front while also acknowledging and being sensitive to the unique interests within the group.

“For the most part, we’ve tried to keep the data at the very center, like what is the science saying, and that should help us drive a decision more than some of the political tensions between the different users,” she said.

Another key component for crafting a successful GSP, Sicke said, was being fortunate enough to have a well-managed aquifer and access to surface water, making groundwater a backup plan. But she said it was the collaboration of so many unique interests that helped its success.

“It was viewed as more of a team effort, and it seemed like it didn’t result in a lot of negative comments from the plan we created, which I think DWR viewed that well,” she said.

Proactive outreach to local and state environmental entities, such as The Nature Conservancy and California Department of Fish and Wildlife, helped engage them in the conversation, ensuring they were informed about the plan and its objectives.

“We haven’t hit the mark totally on groundwater-dependent ecosystems or interconnected surface waters, but I think us engaging them during the planning development made them feel like we were at least trying and putting our best foot forward,” Sicke said.

There was a significant effort by many of those entities to comment on the plans as well, which she said was mostly done in a very positive way.

“I think they recognized we were working with them and we weren’t ignoring it altogether,” she said.

Navigating the Challenges

One of the largest hurdles while developing their plan was navigating some of the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, explained Sicke.

“Developing a plan that you’re supposed to have large workshops for outreach during a pandemic is just exhausting,” she said. “We were really hitting our heads against the wall; how do we communicate with people and have effective meetings?”

Zoom meetings worked for some but were a challenge for seniors who weren’t as familiar with the required technology to meet in an online setting. Another obstacle was rolling out a draft GSP they publicized as sustainable and visionary, but felt a little disingenuous to some, as the drought was still in full swing.

Sicke said she ended up writing a preface to the GSP, hoping to alleviate some of those hard feelings. It explained their plan was developed based on a specific period of hydrology and did not account for the drought conditions of the time but acknowledged they were being attentive to the unprecedented drought conditions and declining groundwater levels.

“I kind of made some promises about what we’re going to do moving forward and not act like our head is buried in the sand and that we will start to consider demand management strategies because our plan didn’t have any,” she said. “I don’t know if it helped, but at least it helped me feel better to be a little bit more transparent.”

The Work Isn’t Done

As SGMA continues to be implemented and the priorities and boundaries of some basins change, DWR says new GSAs will likely be formed and existing ones may need to reorganize, consolidate or withdraw from managing all or part of a basin.

For YSGA and every other GSA with an approved GSP, that means an extensive review known as a periodic evaluation of their plan every five years. While their 2022 plan was conditionally approved, Sicke said DWR will want to see several things clarified in the periodic evaluation.

“Thankfully, I think DWR is being pretty realistic about not needing to do a brand-new plan but focusing on the areas that need to be enhanced or modified,” she said.

As they move forward, Sicke said they will continue to engage stakeholders in several ways. Given the county’s unique hydrogeology, they have identified six distinct areas, each slated to have its own advisory committee. These committees are currently being chartered and are expected to be launched soon. The plan also includes holding biannual community meetings in each area to provide updates on groundwater levels and discuss relevant projects and management actions.

“I’m hoping that really allows for a better opportunity for us to have people come and get an update and also share any concerns they may have,” she said.

Sicke said she wants growers to know YSGA will continue to effectively implement their plan in the best way they can based on constituent needs.

“It’s in our mission to ensure we have continued access to groundwater,” she said, “We want to be there for the [growers] in our area, no matter what crop they’re growing, to make sure they have access to groundwater in dry years.”

Kristin Platts | Digital Content Editor and Social Correspondence

Kristin Platts is a multimedia journalist and digital content writer with a B.A. in Creative Media from California State University, Stanislaus. She produces stories on California agriculture through video, podcasts, and digital articles, and provides in-depth reporting on tree nuts, pest management, and crop production for West Coast Nut magazine. Based in Modesto, California, Kristin is passionate about sharing field-driven insights and connecting growers with trusted information.