The ancient and adaptable chestnut tree is quickly taking root in Western orchards.

Dozens of California, Oregon and Washington growers are now growing the nut, whose forests once provided food and shelter for North American residents. Today, hybrid plants grown in the West are not as susceptible to the blight that destroyed in the early 1900s the native chestnut forests that grew chiefly East of the Mississippi. Although the blight occasionally occurs in the West, chestnut’s hybrid relatives seem to weather the disease, positioning the West as a welcoming host for chestnut’s revival.

At least that’s what growers here are hoping.

(all photos by G. Oberst.)

Numbers Add Up to Potential

One need only look at recent (2022) USDA statistics to see the U.S. has potential when it comes to chestnuts.

Although about 1.36 million acres are suitable for chestnut production in the U.S, just over 10,000 acres are planted on 2,843 farms nationwide. In Western Oregon, Washington and parts of Northern California, less than 2,000 acres are in chestnut production, according to USDA’s 2022 Census of Agriculture.

But Western growers are catching on. That acreage has more than doubled in those states since the 2017 census. Although Michigan and Florida are top U.S. producers, California, with 1,169 acres, up from 370 acres in 2017, and Oregon at 233 acres, up from 202 in 2017, round out the top four producers, according to USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS).

The global chestnut market reached $3.7 billion in 2023 and is expected to reach a total market size of $4.9 billion by 2032, according to a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization. U.S. production makes up less than 1% of the total market.

Of course, numbers don’t explain what’s happening on the ground or the challenges to grow, harvest and market a nut that was once a staple in American diets but has faded from the national memory. Chestnuts continue to play a central role in Europe as well as Asia, where 80% of the world’s nuts are grown and consumed.

But the potential for growing chestnuts has not escaped experimental Western orchardists.

Western Orchardists Build from Scratch

In the 1980s, U.S. scientists and growers began looking for ways to revive the chestnut industry.

The late Randy Coleman of McMinnville established RC Farms, one of the first chestnuts orchards, in 1988 in Oregon, planting four acres of hybrid nuts he’d gotten from Bob Bergantz, a chestnut grower in California.

Today, Randy’s daughter Brenda continues to farm and market 14 acres, including the original Bergantz and the Colossal chestnut, now a staple among Western growers.

“At the time I started, total chestnut acreage in the U.S. was 50 acres,” Randy said on RC Farms’ website.

Twin brothers Bob and Bill Knopp had been growers and nurserymen off and on since childhood when their parents bought the 50 acres the family still owns near Canby, Ore. in the Willamette Valley. The brothers expanded the farm to four times the size and operated a successful nursery, selling it when Bill died in 2021. What Bob didn’t part with was the brothers’ 15 acres of chestnuts planted in 2015 as an experiment. Today, Bill’s son Jack helps his uncle manage Willamette Valley Chestnuts. Seven cultivars (mostly Colossal and the Bouche de Betizac) are now various ages, from 20 years old and younger, despite losses from an unusual ice storm that took out trees that had to be replaced.

Family-run operations like the Knopps’ face other challenges, but not much pressure from Cryphonectria parasitica, the blight that devastated historic stands in the Eastern U.S. While research for blight-resistant cultivars and public U.S. demand for the nut have recovered some of the orchards east of the Mississippi, West Coast orchards have proved generally resistant thanks to hybrids and orchards that are still far apart, reducing chances of cross-contamination. Western interest in growing chestnuts prompted the formation of the Western Chestnut Growers, which in 1996 became the national nonprofit Chestnut Growers of America (CGA). More than 100 members share science and other information about the nut, from species and cultivars to planting and care. Its board of directors includes Steve Jones of Colossal Orchards in Selah, Wash.

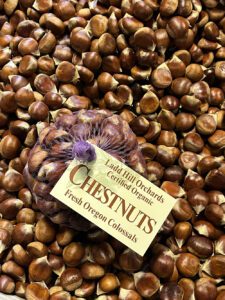

In 1992, Ben and Sandy Bole began Ladd Hill Orchards, a certified organic chestnut farm near Sherwood, as a retirement project. With few resources available to growers in those days, Ben, a former engineering executive and machinery salesman, modified hazelnut harvesting and processing equipment to sort his chestnuts. Today, the Boles say their orchard is one of the largest chestnut producers in the U.S.

Marketing the Unknown

In addition to unusual weather, deer, blossom-end rot, root rot, hazelnut worms, borers, gall wasps and beetles can still do damage to the crop, according to CGA.

But possibly the biggest challenge to Western growers is marketing a crop in the U.S. to a population that has lost its memory about the nut that was once an American staple, according to Brenda Coleman. “We’ve lost chestnuts as a staple out of our diet,” she said. Like many growers, Coleman sells RC Farms chestnuts online, at the farm or at farmers’ markets. To entice the public to resume its love for chestnuts, many growers post recipes and preparation instructions. Irene Coleman, Randy’s widow, went a step a step further, compiling a chestnut recipe book that is for sale online.

There are a few chestnut distributors in the West (e.g., Charlie’s Produce and Organically Grown), but most growers find themselves in the role of both marketers and educators. Brenda Coleman said she attends public festivals and educational and agricultural events to get the word out about the nut, but promoting an unfamiliar product is time-consuming for small family farms whose owners, if they aren’t already retired, take time off from other jobs to manage their orchards.

Still, the Boles suggest it has been worth it.

“It’s fun,” Kristen said, recalling the first crop of nuts, one bucket, picked by hand four years after planting. Today, 15 years later with 150 orders waiting to be filled and sent all over the U.S., the crop is measured in bins, not buckets. “We don’t want people to think chestnuts are a money-sink; it can be a good business,” she said.

The Boles’ adult children and grandchildren visit the farm during the month-long harvest season to help sort and market the nuts. Ladd Hill Orchard’s nut harvest, as is the case at many orchards in the fall, is an excuse for a working family reunion.

Early Europeans arriving on American Eastern shores found portions of its forests dominated by the America chestnut and quickly used the rot-proof lumber for building and the nut for food. They might have recognized the chestnut from home; as long as 85 million years ago, fossil records of 13 related chestnut species have been found in Europe, Asia and North America, according to the American Chestnut Foundation, a nonprofit working to restore the American chestnut in its native habitat on the East Coast. Today, hybrid European and Asian species are grown for their productivity and their resistance to Cryphonectria parasitica.

Despite their continuous fight with the blight, orchardists in states east of the Rockies are also expanding acreage, according to USDA-NASS’s latest report.

The blight has not found any significant foothold in the West as European-Asian hybrids planted here have co-evolved with the blight for thousands of years. Infected hybrid trees often aren’t fatally wounded, and live for many years, but are still isolated, according to federal pathologists at the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization.

“The difficulties, but also the success, in holding the blight in check are shown by the work on the Pacific Coast of North America,” wrote Flippo Gravatt, a pathologist, in a report to the U.S. Forest Service about controlling the worldwide spread of the disease.

The West has taken measures to ensure its chestnuts remain blight-free. Fresh chestnuts can be shipped out of Oregon, Washington and California, but, with some variations, state agricultural regulations prohibit all chestnut materials (plants and nuts) from being shipped into those states.

This bodes well for the Western market on several fronts: It has little outside competition coming in, and because pests are rare, growers report using fewer chemicals, if any, in their orchards.

Eating Chestnuts

The unusual chestnut, which looks like an outer-space alien as it grows, is not like a dried or roasted walnut or hazelnut, which requires only a crack to access the meat. The raw chestnut must be cooked, either roasted or boiled (see sidebar), and then peeled through two layers. Scoring the shell prevents explosions. And roasting on an open fire, as in the song? Not recommended, Bole said, preferring boiling or oven roasting. Uneven heat can create tough or uneven nut meat.

Chestnut Preparations (Ladd Hill Orchards)

Ladd Hill Orchards near Sherwood includes a brief instruction sheet with each sale, and it on its website offers a special bird’s beak paring knife for scoring the outer shell.

Instructions

Slash an X on the flat side of the nut. Follow either of the methods below:

• Roasting: Place on a cookie sheet. Bake at 350 degrees F for 15 to 20 minutes

• Boiling: Cover with cold water, bring to a boil, cook 5 to 7 minutes.

Remove nuts from pan, wrap in towel to keep warm. Peel off both the hard outer shell and the inner skin with a sharp knife. The nuts are ready to eat!

Serving ideas

Add halved, cooked chestnuts to green beans, Brussel sprouts or sauteed mushrooms.

Include chestnuts in your favorite stuffing recipe, especially those with fruit.

Add to apple pies, crisps and cobblers.

Roasted Chestnuts (RC Farms)

Peeling the chestnuts after they are roasted can be part of the holiday fun, Brenda Coleman said. “Chestnuts are like popcorn. You can dress them up or dress them down and make them savory with seasonings like salt, pepper, rosemary, thyme, sage, or make them sweet with cinnamon sugar. I personally love them drizzled with olive oil and rosemary,” she said.

Instructions

500g chestnuts (1.1 lbs.)

1. Rinse the chestnuts thoroughly and soak them in water for 15 minutes.

2. Use scissors to cut each chestnut. This method is quicker and safer than using a knife, reducing the risk of injury.

3. Place the chestnuts in a pan and add just enough water to barely cover them.

4. Add 2 tablespoons butter (or cooking oil), and 2 tablespoons sugar to the pan

5. Cook the chestnuts over medium heat for 10 to 15 minutes, until most of the water has evaporated and the chestnuts are tender.

6. Turn chestnuts regularly to prevent the skins from burning. Once the water has evaporated and the chestnuts are cooked through, remove them from the pan.

7. Optional seasoning: Add 1/2 teaspoon salt for extra flavor, if desired.

8. Serve roasted chestnuts to guests. Easy to peel and delicious, perfectly cooked.

Gail’s Chestnut Teriyaki Noodles

Serves one, or double the noodles for two.

Ingredients

• 1 dozen chestnuts cooked, peeled

• 1 to 2 cups ramen or rice noodles

• 2 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

• Dash ginger (ground fresh or powder)

• Splash of ponzu or lemon juice

• 1/2 to 3/4 cup teriyaki sauce

• Toppings (sesame seeds and crackers, or grated carrots)

Instructions

1. Boil or roast, then peel about a dozen chestnuts as above. Chop in thirds or quarters.

2. In frying pan or wok, heat olive oil to sizzling. Add dash of grated fresh ginger or powder to oil.

3. Add nuts to hot oil, stir

4. Add cooked ramen or rice noodles, sizzle with dash of ponzu sauce or lemon juice.

5. Add teriyaki sauce to taste, stir until coated.

6. Serve with toppings