Listen to the audio version of this article. (Generated by A.I.)

Years of drought in California, and countless drives down Interstate 5 past open, sunbaked aqueducts, made Jordan Harris acutely aware of the state’s water crisis. Harris, co-founder and CEO of San Francisco-based Solar AquaGrid, had also spent years living part time in France, where canals are routinely shaded by trees. Seeing how those shaded waterways were naturally protected from sun and wind sparked an idea: Could the same concept help conserve water in the West?

His research revealed another startling fact. Nearly 19% of California’s electricity use goes toward moving water, most of it pumped from north of Sacramento. With more than 4,000 miles of canals, the largest water conveyance system in the world, California’s infrastructure was both massive and energy hungry, Harris said.

The Concept

Intrigued by the intersection of water and energy, Harris launched Project Nexus in 2014. His first move was to seek academic partners who could rigorously evaluate the idea, which led him to UC Merced.

“My idea was all around this idea of dual use, getting multiple benefits of already existing infrastructure, already disturbed land, and to both protect open spaces, protect agriculture because solar farms take up a lot of real estate. The idea that we could use this existing footprint and get multiple benefits from it really fascinated me,” Harris said.

Brandi McKuin, a project scientist at UC Merced, is part of the Project Nexus research team and leads the work on assessing the benefits of shading canals with solar panels. After Harris contacted the university, she and her team conducted a feasibility study that was later peer-reviewed and published in Nature Sustainability, evaluating the potential of installing solar over California’s 4,000 miles of major canals.

Their research included a hydrologic simulation and a techno-economic analysis, which showed that using a lightweight tension-cable design could save up to 63 billion gallons of water each year. The study also highlighted key co-benefits, including avoiding land purchases, reducing aquatic weed growth and conserving water through reduced evaporation.

“When we factored in all those co-benefits, the cost could be competitive with nearby ground mounted systems, assuming a fixed tilt, ground mounted system on local land nearby. That seems like a promising result and warranted further study with a demonstration,” McKuin said.

Josh Weimer serves as the director of external affairs for the Turlock Irrigation District (TID), the agency hosting Project Nexus. “TID is the oldest irrigation district in California, and we’re one of four that provide irrigation water and then retail electricity to our community. We are constantly looking at ways in which we can be the best stewards of our water resources, and provide reliable and affordable power to our customers,” he said.

California has set ambitious climate and clean-energy mandates, and TID has 20 years to achieve zero-carbon power on the retail side of its grid. To meet those targets, the district is continually evaluating projects that can help them get there in a reliable and cost-effective way.

“Back in 2021, we were doing some analysis of some property that we owned in the TID service territory, and said, ‘Hey, can we put some renewable energy on some of these sites?’ And then the UC Merced paper came out that really kickstarted this whole Project Nexus,” Weimer said, adding that once the paper was published, TID called UC Merced to express their interest in exploring the idea further.

This wasn’t the first time people had floated the idea of covering canals with solar panels, but it was the first time a detailed engineering analysis laid out the potential co-benefits. “Those co-benefits are really what piqued our interest,” Weimer said.

The Research

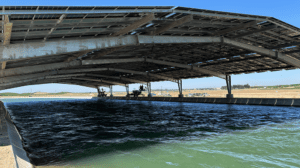

The research kicked off at two sites along the TID canal system, one on a narrow canal segment and another on a wider section. UC Merced is evaluating the benefits at both locations, McKuin said.

“We’re trying to learn what are the water savings, and what are the other benefits and challenges of doing this. We’re going to learn from Turlock Irrigation District what their experience is with maintenance because that’s definitely one of their main concerns, is making sure they can reliably provide water and power to their ratepayers. We’re learning a lot from them, and on what the operation and maintenance impacts are on both the canals themselves and the panels. We’re testing out a few different prototypes,” McKuin said.

Most canals in California are relatively narrow, but some stretches, like portions of the California Aqueduct, are significantly wider. Depending on the location, the aqueduct ranges from about 40 to nearly 400 feet across.

“We want to demonstrate that this can be done on a variety of types of widths and azimuth, so we’re doing that with two different project locations,” McKuin said.

One of TID’s pilot sites is a narrow-span location in Ceres, Calif., where the canals are roughly 20 to 25 feet wide. The second is a wide-span site in Hickman, with canal widths of about 110 feet, indicative of the California Aqueduct canals.

“My idea was all around this idea of dual use, getting multiple benefits of already existing infrastructure, already disturbed land, and to both protect open spaces, protect agriculture because solar farms take up a lot of real estate.” – Jordan Harris, Solar AquaGrid

The narrow span was built in two phases. “One of those was constructed in the spring of last year (2024), and one was constructed in the fall,” Weimer said, adding the wide span has been producing power since July of 2025.

McKuin is studying evaporation using a suite of meteorological sensors that measure all components of net radiation, including incoming and outgoing shortwave radiation, as well as long-wave radiation emitted from the Earth and atmosphere and what’s reflected. The team is tracking key meteorological factors such as air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed and direction, along with the water’s surface temperature.

Three different prototypes are being installed at TID, the first, a vertical array, was followed by a large canopy design that was commissioned in March of 2024. “It’s been generating electricity, and we’ve had sensors measuring the meteorological parameters we need to estimate the evaporation, and we’re just about done collecting a full irrigation season’s worth of data. We’re working on writing that up right now,” McKuin said.

The final component of Project Nexus is scheduled for installation in early 2026, Harris said. It comes from an Australian company called Solar Waves, a retractable solar array that operates on ground-level rails. The system can fold up and slide aside, giving crews rapid access to the canals when needed.

Because the array sits at ground level, it eliminates the need for elevated structures. Elevating solar requires extensive steel, deeper foundations, higher material costs and, ironically, can reduce the system’s ability to limit evaporation.

The research will continue for multiple years, McKuin said. “We’re working on a first draft of the report, so we’ll be reporting on the narrow span prototype because we have a full irrigation season, and the wide span array was just commissioned in September 2025, so we’re really looking forward to collecting more data on that, so we have a full picture.”

Co-Benefits

The primary goals were to cut evaporative losses and generate renewable energy without using additional land, but as the research has moved forward, several additional co-benefits have emerged. “One is the reduction in aquatic weed growth,” Harris said.

“Our team at UC Merced has placed sensors on all of the arrays that we’ve installed, and they’ve been collecting data on reduction in evaporative losses, and reduction in aquatic weed growth,” Harris said.

“We really want to see the value and the quantifiable data for all these co-benefits,” Weimer said.

Weimer said they made it clear to both the state and UC Merced that while any evaporation savings would be a welcome bonus, it isn’t their primary focus. The district already has major automation projects underway that are delivering far more significant water savings across the system, so evaporation reduction isn’t a key driver for them.

Weimer said one of their biggest interests on the water side was whether shading the canals would reduce aquatic weed growth, as the study predicted. And so far, that’s exactly what they’re seeing. When the canals are drained, there’s a noticeable line showing where the weeds stop, right at the edge of the shaded area under the solar panels.

Aquatic weed growth is a major challenge for canal systems. Because TID’s network is gravity-fed, unmanaged vegetation can break loose and travel downstream where it could clog gate structures, cause localized flooding or block growers from getting the water they need, Weimer explained.

“We spend over a million dollars annually to clean and maintain our canal system, and there’s obviously hot spots of more weed growth, and we do a lot to try to maintain that. The reduction in aquatic growth is probably the most interesting water metric that we’re really interested in,” Weimer said.

Interest Across the World

Interest has come from far beyond the United States. A water district in Romania visited to explore the possibility of installing similar systems along the Danube River. Delegations from Ukraine and Saudi Arabia have also toured the project, and Harris has held meetings with groups from Vietnam, Brazil, Costa Rica and three separate water districts from Spain.

This is a global issue and opportunity, he continued. “There is certainly heightened awareness with climate change, and here in California. The state is predicting that we’re going to have 10% less water by 2040. There are a lot of people paying attention to Project Nexus so that they can learn from it.”

Harris said they’ve been developing a suite of technologies because no two canals are alike. The geography, soil conditions, elevation and whether the canals are lined all vary. He added that the top priority for operations and maintenance crews is preserving full access to the canals, and the goal is to design systems that never interfere with that access but instead support and enhance their work.

The Future

“I think other districts are really going to be watching how it’s going for Turlock Irrigation District, and the reports that are going to be coming out of this project to really understand what the potential benefits and risks to them are. I think one question at the top of everyone’s mind is, what is this going to cost?” McKuin said.

“This is an important part of that puzzle,” McKuin said, but the research is promising. “I would say we’re very encouraged by the results that we’re seeing so far, but we’re going to need a little more time to really understand what the operation and maintenance impacts are to the district.”

The team is also taking the research a step further, McKuin said. Once the pilot study results are in, they’ll use that data to estimate how the technology could perform in other parts of the state, a process they’re calling the scale-up study. While they continue gathering field data, they’re also refining the statewide projections from their earlier research to get a more accurate picture of the overall potential.

Weimer emphasized that the goal is to demonstrate the project can be built and adapted to a wide range of situations. Each agency will have its own version of success because every system is designed to meet different needs. A water-focused district might prioritize evaporation savings, while others could use the solar generation to offset local energy demands. Some agencies may even treat their canals or aqueducts like a built-in land base, using them to create a new revenue stream. The potential use cases are broad, he noted, and depend entirely on what each organization is trying to solve.

“UC Merced is putting out their paper next summer. We’re also putting out a builder/project owner/developer paper that details all the experiences that we had going through different design components and changes along the way. That’s really what a lot of water agencies are very interested in, is, how’d you guys actually build it? Whenever we talk to people, that’s what they want to know,” Weimer said.

The district will ultimately choose whatever option makes the most financial sense for its ratepayers, which is why they want a solid understanding of all the co-benefits, Weimer said. Having that full picture will allow them to compare this project with others and fairly evaluate its overall value.

Scaling Solar Canals

Recognizing that California’s canals vary widely in design, geography and purpose, Solar AquaGrid, together with its partner, USC Dornsife Public Exchange, has assembled a multidisciplinary research team from faculty at seven universities: USC, UC Merced, UC Berkeley, UC Irvine, UC Law San Francisco, San José State University and the University of Kansas.

This team will explore the most promising opportunities to scale solar canal systems across stretches of California’s 4,000 miles of canals that are well suited for solar infrastructure. These researchers will closely collaborate with the state agencies responsible for water, land and energy, the California Department of Water Resources (DWR), the California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA) and the California Energy Commission (CEC).

Other Technology

Harris has also worked on floating solar concepts. He said they had been preparing a floating-solar demonstration on a federal reclamation canal, funded through the Inflation Reduction Act. The project was scheduled to begin earlier this year, but the federal government froze those funds. Even so, he noted there may be future opportunities to pursue the idea.

“We really believe that’s a technology that may work in certain areas because it eliminates any construction. You’re literally floating these things out there, tethering them to the shores,” Harris said.

This approach is likely best suited for drinking-water canals that operate year-round. By contrast, irrigation districts typically have defined irrigation seasons, and their canals are drained for major maintenance, Harris explained. He added that the goal isn’t to create a one-size-fits-all solution, but rather a repeatable, modular design that different agencies can adapt to their own systems.