Listen to the audio version of this article. (Generated by A.I.)

“There is a lot of misinformation out there,” UC Davis extension apiculturist specialist Elina Niño said in her opening remarks at The Almond Conference.

Claims that no honeybee pollination is needed for good yields in self-compatible almond varieties orchards are unsubstantiated. Those claims can cause problems to agriculture at large, Niño said.

Stocking rates for self-compatible almond varieties are not set in stone and are still a work in progress, Niño noted, saying that the Independence variety has been around since 2008 and work continues to deliver growers a clear answer about beehive stocking rates.

While the honeybee hive stocking rate for conventional almond varieties has remained constant at two hives per acre, there is an assumption that due to the self-compatibility of the trees, using honeybee colonies for pollination could be eliminated, reducing input costs. Impact of this reduction is not fully understood, Niño said.

A two-year study to determine impact of pollination or lack of on almond yields provided some answers about stocking rates. Niño said that self-compatible Independence trees that received honeybee pollination show about a 20 percent increase in kernel yield per tree compared to bee-isolated trees. In the study, Comparison of Yield Characteristics of Independence as Affected by Presence of Honeybee Pollinators, the economic model suggests specific honeybee hive stocking density recommendations, considering that the surrounding landscape will likely change as the acreage of self-compatible varieties continues to increase.

In the first year of the study, individual trees were caged to exclude bees and three branches per tree were tagged to assess branch-level nut set. Cages were in place for four weeks and at harvest yield was assessed along with nut quality, kernel size and dry weight. The second year of the study focused on impact of stocking density on floral visits and nut production. Each of three orchards were stocked with zero, one or two hives per acre.

Niño said the study found clear economic gains at stocking rates of 0.5 and 1 hive per acre. There were no additional yield benefits for trees in orchards stocked above one hive per acre. According to their economic model, the gain from stocking honeybees in self-compatible orchards creates sufficient economic value to compensate for the cost of hive rentals.

It is up to the grower to decide individual orchard stocking rates, noting geographical and regional differences between orchards, Niño said.

Bee Challenges

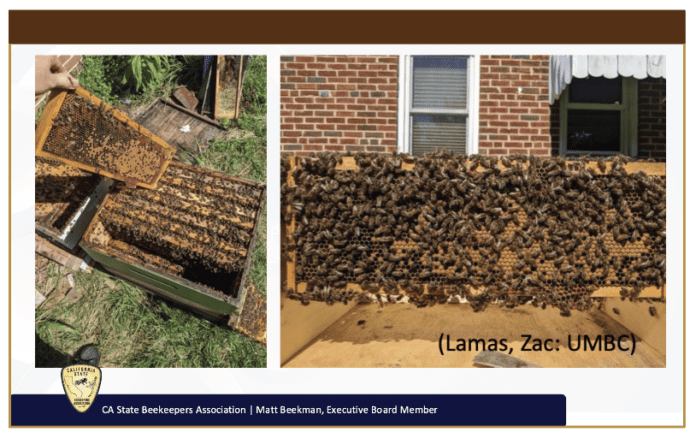

When describing the state of the bee industry, beekeeper Matt Beekman cited the four biggest challenges to bee health: parasites, poor nutrition, pathogens and pesticides.

The varroa mite continues to pose a significant threat to hive health, Beekman said, as beekeepers struggle for an effective treatment protocol. There has only been one new chemical treatment to combat varroa mites in the last 20 years, he added, and resistance is an issue. Introduction of new mite species from Asia is also a significant threat to the U.S. apiary industry.

Varroa mites can feed and live on adult honeybees, but also feed and reproduce on larvae and pupae in the developing brood, causing malformation and weakening of honeybees. Mites also transmit viruses which further weaken hives. Beekman said low-level mite infestations may have few early symptoms, but as the infestation builds, there are significant impacts on individual bees and hive strength. Symptoms of a varroa mite infestation include abnormal brood pattern, sunken and chewed cappings, and larvae slumped in the bottom or side of the cell. With the loss of brood comes colony breakdown.

California State Beekeepers Association’s snapshot of an experimental colony showed a relative parasite burden of 14.6%, but the parasite burden on worker bees was at 59.9%. On drones it was 96.6%. Significantly more bees are parasitized as adults than bees parasitized during development.

Poor nutrition comes with the loss of native forage for bees. Beekman cited the loss of hive placement on federal lands and Conservation Reserve Program land. It is the pollen from native plants that provides an important protein source for bees, while plant nectar provides carbohydrates.

The use of organosilicone surfactants also impacts bee health, he said.

Beekeeper income has also declined with the dramatic increase in honey imports and adulterated honey.

A financial snapshot of beekeeping costs from 2024 shows the annual cost to maintain a single commercial colony is $350. Pollination rental covers $200. The national average of price per pound and average national yield per colony is $139.07. Average price per pound of honey is $2.69. U.S. honey production has dropped below 1991 production to under 200 million pounds. Honey imports have risen sharply to nearly 500 million pounds, according to USDA-ERS statistics.

Improved miticide treatments, more access to native forage and research into mite-transmitted viruses are necessary to the strength of the industry, Beekman said.

Almond Board of California has stepped up to meet some of these challenges, said Josette Lewis, chief scientific officer at ABC. From cover crop incentives to studies on pesticide adjuvants, the industry has supported the apiary industry, noting its importance to almond production.

Panelist Alexi Rodriguez with Almond Alliance noted several industry responses to pollination needs for managed and native pollinators.

The California Pollinator Coalition includes more than 20 organizations pledging to increase habitat for pollinators on working lands.

The collective land will address habitat for the benefit of beneficial insects, such as bees, butterflies, beetles, wasps, moths and other pollinator species. The coalition is promoting voluntary habitat establishment projects and Integrated Pest Management (IPM) practices.

Another Almond Alliance initiative, the Pollinator Alliance, promotes pollinator health and habitat investment. A partnership with Great Valley Seed was formed to help growers with a cost-effective seeding program to establish forage for managed and native bees.

In a rare private-public agreement soon to be finalized, a Conservation Benefit Agreement with the state Fish and Wildlife Services protects growers who take steps to protect beneficial species. Rodriguez explained that when a grower follows established IPM practices, they cannot be held liable for species losses.

Cecilia Parsons | Associate Editor

Cecilia Parsons has lived in the Central Valley community of Ducor since 1976, covering agriculture for numerous agricultural publications over the years. She has found and nurtured many wonderful and helpful contacts in the ag community, including the UCCE advisors, allowing for news coverage that focuses on the basics of food production.

She is always on the search for new ag topics that can help growers and processors in the San Joaquin Valley improve their bottom line.

In her free time, Cecilia rides her horse, Holly in ranch versatility shows and raises registered Shetland sheep which she exhibits at county and state fairs during the summer.