The honey bee may be small in size, but the impact it has on agriculture is enormous. It has been reported the value of the European honey bee, Apis mellifera L., to pollination services is estimated to be more than $217 billion globally and $20 billion in the United States annually.

In California alone, about one-third of agricultural revenue comes from pollinator-dependent crops.

In the world of nut crops, the honey bee is as important to the crop as the crop is to the bee. And no nut crop needs them more than California almonds. And likewise, no single crop matters more to beekeepers’ bottom lines than the state’s almond pollination, which is reported to make up over a third of U.S. beekeeping revenues.

The critical role of the honey bee is well researched and documented at the E. L. Niño Bee Lab at University of California (UC Davis). The Lab’s stated goal is to “characterize biotic and abiotic stressors affecting colony health in order to inform development of immediate and long-term solutions for bees and beekeepers.

This message was the basis of a presentation by Bernardo Nino, bee lab researcher, during this year’s Nickels Soil Lab Field Day. He discussed a grower’s relationship with the beekeeper, Varroa research, and ways grower practices can benefit bees and beekeepers.

Growers and Beekeepers

Beekeepers, also known as apiarists, utilize the natural population dynamics of honey bee colonies to produce honey and provide pollination services.

“If I were a grower, and knowing what I do about beekeepers, the ideal situation would be to have a longstanding relationship with a good beekeeper,” Nino said. “Having a lot of communication with your beekeeper and having someone who is close to where your orchards are can be greatly beneficial for both the grower and the beekeeper.”

This close proximity may even lead a beekeeper to give the grower a discount as it reduces transportation stress of the colonies and saves on mileage costs.

“However, that can’t be the situation for everyone,” Nino added. “So, how do you get the bees in your trees?”

There are other options, he explained, such as brokers, like Pollination Connection. He said a grower can go online and type in the words “pollination and broker” and be able to come up with a broker company.

“For instance, if I were a beekeeper in Texas, I might send all of my hives to California in October and not worry as I pay a broker to both take care of them, which at that time of year would be feeding and treating, and finding contracts with growers,” Nino said. “As an example, let’s say I’m a grower, I need to find the right broker, tell him I need 10,000 colonies in my orchards and the broker can take care of me because he is managing 40,000 hives for a beekeeper out of Texas.”

In this type of situation, a grower is once-removed from direct contact with the beekeeper, and will really have to trust the broker, and in turn, the broker will really have to trust the beekeeper.

“There are a lot of different contracts out there,” he added. “I have been amazed at the variety and nuances in details and numbers. It is a very personal decision for the grower.”

With so many honey bees colonies being transported from out-of-state into California for pollination purposes, transportation stress can result in a 5-10 percent loss just on the truck, Nino said.

“There are so many variables that can take place before the bees make it into the orchard in January and February,” he added. “That in turn can cause stress between the beekeeper and the transporter, then to the broker, and on down the line from the broker to the grower.”

Honesty and integrity is another reason for a grower to have a good relationship with a broker or beekeeper.“A grower needs to be able to know for surety that the colonies he is receiving into his orchards is exactly what he contracted for,” Nino explained. “As is any business, there can be unscrupulous people out there. For instance, as a beekeeper, if I was less scrupulous, I could do some manipulating of the hives and make it look like an eight-frame colony, when it isn’t. And you may unfortunately even have an inspector who only cracks the lid, and grades it as an eight frame.

However, if it doesn’t have the proper frames of brood, if the demographics are off, then it’s not going to work your trees like a normal colony.”

Nino said such is very seldom the case and the vast majority of beekeepers do all they can to provide the best quality product to their growers.

“Otherwise, they would have few repeat customers,” he added.

The world of a beekeeper is menacing enough, with so many things that can go wrong and do go wrong, that the relationship they have with the grower is as important to them as it is to the grower.

“Let’s say, in November a beekeeper is working to equalize hives and at the same time really trying to communicate with the grower concerning his numbers, and keeping his fingers crossed that nothing adverse happens to his colonies from Thanksgiving through New Years,” Nino said. “And then it is a mad dash for the beekeeper to try and get the actual numbers, which is very difficult to do, then communicate those numbers to brokers and growers with the hopes nothing wrong happens in the meantime. It is perilous for everyone involved due to the critical role of the honey bee in the success of the crop.”

Bee Threats and Stressors

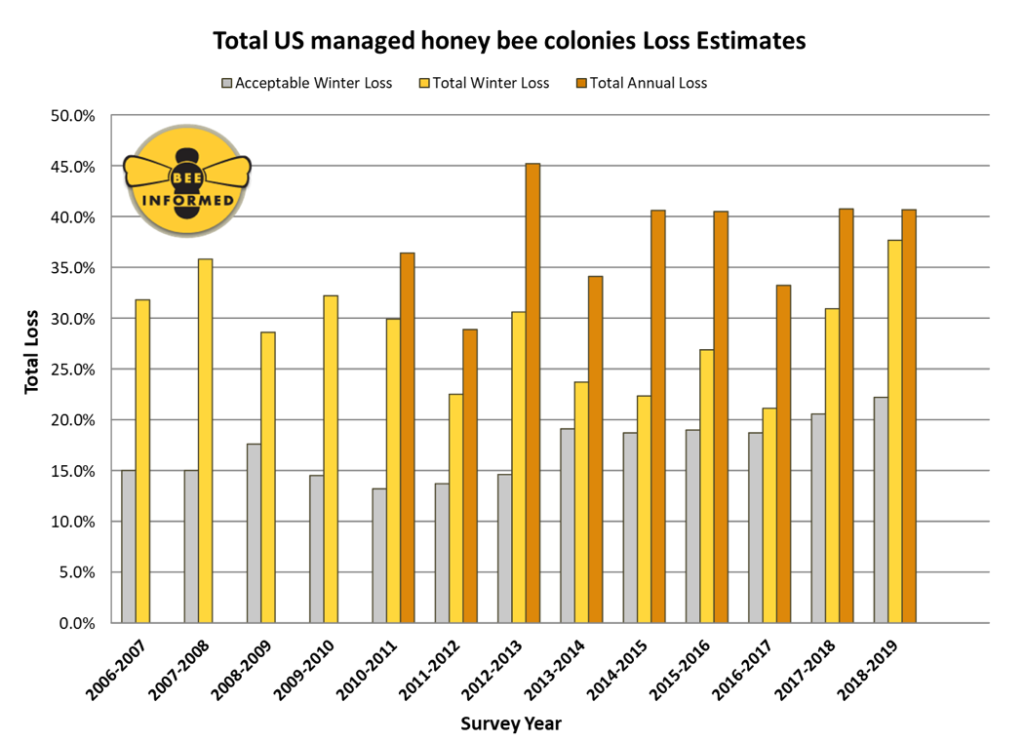

Honey bee colony loss rates have almost doubled to 28 percent since the early 2000s due to a combination of stress, pests, diseases and pesticide exposure, according to research reports.

Along with moving colonies from place to place, lack of forage, cold weather and exposure, there is the threat to the hives of the Varroa mite, a parasite that transmits viruses and lowers bees’ immune systems. It is about the size of a basketball on a bee, comparatively, and is a physical hindrance which is more so when colonies are in stressful situations.

According to the Nino Bee Lab, Varroa destructor mites were first found in the USA in the late 1980s. They made their way from Asia, evolving to specifically reproduce on the European honey bee and devastating the U.S. beekeeping industry.

Varroa mites are still considered to be the number one ectoparasite of honey bees. Colonies that have high Varroa mite numbers (above the three percent threshold) late in the season are highly likely to die over the winter season, reports the Lab.

Beekeepers have a limited number of options for managing these mites and these include hygienic bee stock, host-parasite biology manipulation, and varroacides. Chemical treatments present a particular challenge as Varroa mites can quickly develop resistance and some treatments can be harmful to bees if not properly applied.

Nino said, “Bees have a tendency to drift and lob, and so pollination is like summer camp for bees, where for them it’s like ‘oh look, a bunch of hives and we can share our diseases and be super close.’ You have a lot of stress on the bees at that time of year and stress can lead to pests and disease.”

In the Nino Bee Lab, Nino is joined by researchers Elina L. Nino, Christina Torres, Robin Lowery, Nissa Coit, and Gehrig Loughran, in an ongoing project working with several entities and supported by The IR-4 Project to evaluate and develop a new soft chemical for managing Varroa mites in a manner safe for the bees.

Thus far the researchers have evaluated several new products or new formulations of existing products, and while they can’t divulge details the report, there are several good prospects.

Research

Nino said one of the areas of research concerns the question of colony frame size and what stocking rates work best for pollination.

“The question remains, while a four-frame colony is not going to be able to do the work of an eight-frame colony, however, if I have a four-frame colony out there with a 12-frame colony as well, is that just as good as having two eight-frame colonies, or even better? We are going to use two hives per acre as a minimum, and try to discover if using two four-frame colonies equals the work and outcome of one eight-frame colony,” he added.

Current research, Nino said will be critical when trying to evaluate a year such as 2019, a year beekeepers did not have good, strong bees as they have had in the past, and they are still trying to figure out why—was it from pesticide exposure, the mite levels and viruses.

“It has been really hard to define and explain why a colony didn’t perform well or even died,” Nino added.

He said one thing they have done in the lab is to investigate the ideal supplemental forage.

“The Almond Board of California and Project Apis M are working with us to evaluate orchards, for example that might have a mustard field next to it in comparison to an orchard with just bare ground around it,” Nino stated. “So what we found is, hives that were placed in mustard-bearing orchards had higher strength of about three frames of bees in December, which is huge for beekeepers, and could be the difference of being able to make the required numbers for contracts, or not. We found that we had fewer hives die that were in the orchards with mustard.”

Planting mustard is just one of the things, he said, that growers can do to help the beekeepers, and in turn help themselves. It is a low investment for the return.

“There have been voiced concerns that if a grower plants mustard, then the bees are only going to work the supplemental planting and not work in the trees,” Nino explained. “The research has shown that is not the case, that it in fact synergizes the bees and you have more effective pollination because you have created habitat for some of the other pollinators.”

He said growers can plant the mustard in orchard rows or in a separate field.

“Some growers have reported planting in a nearby walnut orchard to leave their almond orchard clean,” Nino added.

Another project Nino said he is involved in concerns stationing cameras in front of colonies to study activity in the hives and at the same time counting bees on the trees to answer the question of “what is the traffic of the colony equal to the work that is being done in the trees on warmer, sunny days compared to colder days.”

“From my data, the bees are really shutting down around 2 p.m. in the trees, even on warm days, although the activity in the hives continues to be busy until later,” he said.