Sitting on a beach at a cousin’s wedding near the equator, seemed an unusual spot to write this months article on winter leaching. There really is no winter and they don’t have to actually purposefully leach bad salts from the ground as Mother Nature handles all of that for them. Unfortunately in the west, we aren’t so lucky. Salts accumulate. Our soils hold much tighter to nutrients and our inadequate water supplies won’t allow us to clean up the bad guys very easily. The flip side is, we have the most amazing soils in the world for fresh produce and nuts. When we get our soils more in balance we can create spectacular quality and yield.

Sitting on a beach at a cousin’s wedding near the equator, seemed an unusual spot to write this months article on winter leaching. There really is no winter and they don’t have to actually purposefully leach bad salts from the ground as Mother Nature handles all of that for them. Unfortunately in the west, we aren’t so lucky. Salts accumulate. Our soils hold much tighter to nutrients and our inadequate water supplies won’t allow us to clean up the bad guys very easily. The flip side is, we have the most amazing soils in the world for fresh produce and nuts. When we get our soils more in balance we can create spectacular quality and yield.

Pumps and Wells

It’s easy as farmers for us to moth ball the wells and pumps when the first rains hit. We waited a bit for those to hit this year but when they came, for the most part, California got hit hard. That’s a good start. But we need to make sure the soils stay saturated so rain water can exacerbate the leaching fraction. Using salty water will require more of it to keep the salinity in the root zone at an acceptable level. If we can get the soil saturated first with the bad stuff we can clean it up easier with more acidic rain water. If we have weeks of no rain or small amounts of it, turn the pumps on. Keeping the soil saturated before the rains hit will have a better effect.

The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) website defines leaching fraction requirements as follows:

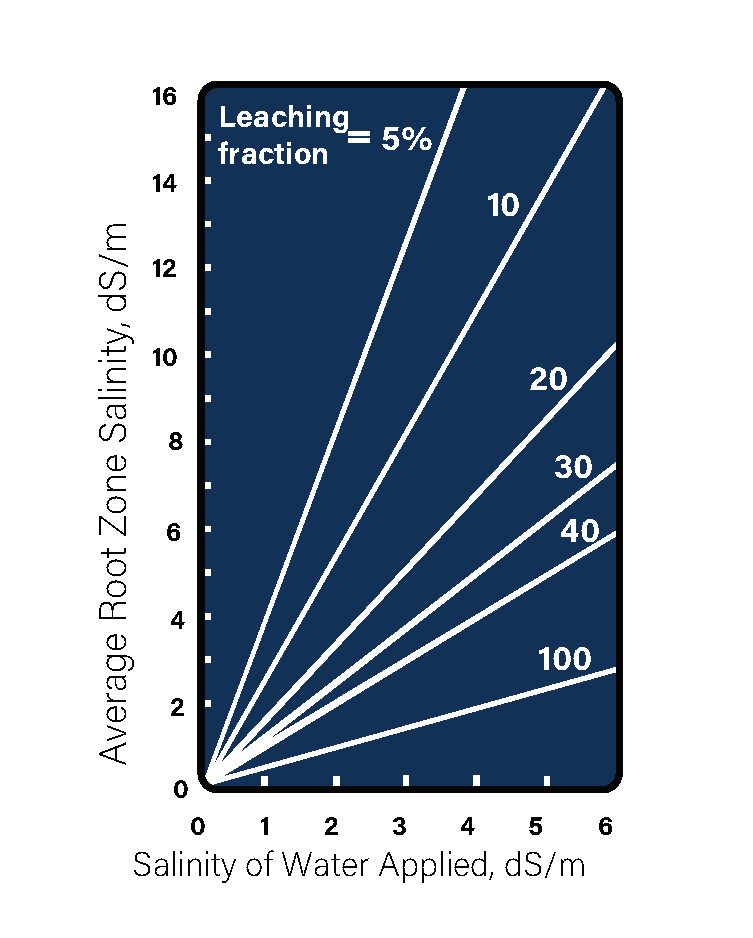

Estimating Leaching Fraction Requirements

The leaching fraction is the amount of extra irrigation water that must be applied above the amount required by the crop in order to maintain an acceptable root zone salinity depending on the salinity of the water it is being irrigated with. To estimate the needed leaching fraction required, decide what soil salinity will be acceptable. Then find the EC (Electrical Conductivity) ds/M (deciSiemens per meter) of the water you are irrigating with. The section where these two lines intersect is the percent of water over and above the crop requirements that must be applied to maintain the desired EC in the root zone. For example, corn can tolerate a root zone salinity (EC) of 1.7 ds/M. If you irrigate consistently with water with an EC of 1.0, you will need to apply 30 percent more water than the crop needs to keep from exceeding 1.7 ds/M in the root zone. These relationships were determined with normal irrigation water. Since some of the EC in lagoon water comes from ammonium and potassium, both of which can be expected to be utilized by the crop, it is possible that the actual leaching fraction needed will be somewhat less than indicated by this chart.”

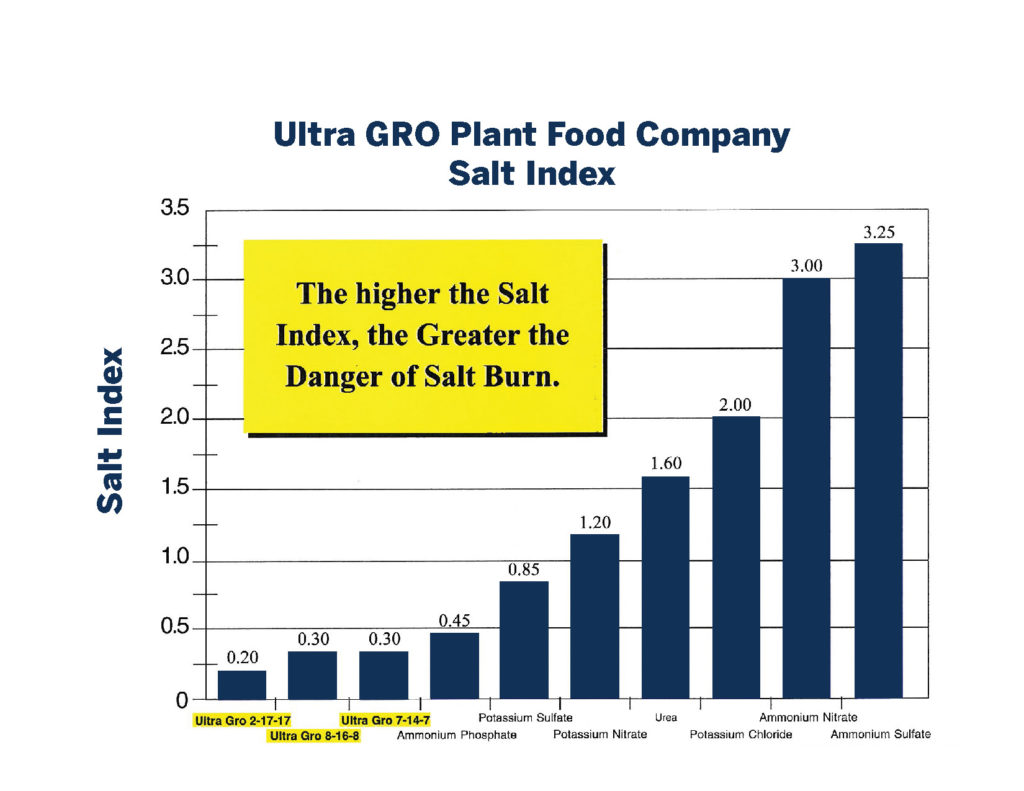

Salinity Index

Every fertilizer is a salt. Calcium nitrate, ammonia sulfate, potassium sulfate, mono potassium phosphate, etc… you get the point. But a fertilizer’s salinity index will give you an idea of how much burn a fertilizer can induce. Ammonia sulfate has a much higher salinity index than Calcium nitrate. Salinity index is a measure of the relationship between moisture and Electrical Conductivity. In essence, when our ground becomes too salty, the ground pulls harder on the soil moisture than the roots can pull on that same water. And as the concentration of detrimental ions like sodium climb, they will be absorbed more readily than a similar ion like potassium. And with the roots working harder, more energy is expended trying to get water up the xylem. Staying alive becomes a priority over making bigger babies.

It is also important to remember that stable salts don’t attach to the soil colloid. They can wedge the ground open to allow water to pass but they won’t displace each other. Calcium sulfate likes to be calcium sulfate. Potassium sulfate is very stable as, you guessed it, potassium sulfate. You have to break apart the salt to make the magic happen. We can help this process along in high pH soils by adding acids to our irrigation water or applying acid directly to the soil. Break apart calcium sulfate, and one calcium ion will displace two sodium ions from the attachment points. Rain water can now drive that sodium out of the root zone. Adding sulfur to the soil will help this process along in the same manner. Carbonic acid, hydronium acid, even citric, humic and fulvic acids will help. Adding more carbon and hydrogen will allow Mother Nature’s blessing of rain water do a better job of cleaning up our soils. And remember, rain water is more acidic than irrigation water…. Get the picture? The EC’s in the soil should also pull that rain water down more easily.

Turning the pumps on during the winter months can be a royal pain the gluteus maximus. But we don’t have to run full irrigation sets if we are just keeping our soils moist. Keep the soil saturated, add some acid to it and let the rain do its job. That spring time bloom will thank you for it and you may even be able to add less overall fertilizer next year and see more than adequate tissue levels. Be proactive this winter and give your soil a good scrubbing. Your trees will shine next spring with clean pipes this winter.

It’s easy as farmers for us to moth ball the wells and pumps when the first rains hit. We waited a bit for those to hit this year but when they came, for the most part, California got hit hard. That’s a good start. But we need to make sure the soils stay saturated so rain water can exacerbate the leaching fraction. Using salty water will require more of it to keep the salinity in the root zone at an acceptable level. If we can get the soil saturated first with the bad stuff we can clean it up easier with more acidic rain water. If we have weeks of no rain or small amounts of it, turn the pumps on. Keeping the soil saturated before the rains hit will have a better effect.

The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) website defines leaching fraction requirements as follows:

Estimating Leaching Fraction Requirements

The leaching fraction is the amount of extra irrigation water that must be applied above the amount required by the crop in order to maintain an acceptable root zone salinity depending on the salinity of the water it is being irrigated with. To estimate the needed leaching fraction required, decide what soil salinity will be acceptable. Then find the EC (Electrical Conductivity) ds/M (deciSiemens per meter) of the water you are irrigating with. The section where these two lines intersect is the percent of water over and above the crop requirements that must be applied to maintain the desired EC in the root zone. For example, corn can tolerate a root zone salinity (EC) of 1.7 ds/M. If you irrigate consistently with water with an EC of 1.0, you will need to apply 30 percent more water than the crop needs to keep from exceeding 1.7 ds/M in the root zone. These relationships were determined with normal irrigation water. Since some of the EC in lagoon water comes from ammonium and potassium, both of which can be expected to be utilized by the crop, it is possible that the actual leaching fraction needed will be somewhat less than indicated by this chart.”

Salinity Index

Every fertilizer is a salt. Calcium nitrate, ammonia sulfate, potassium sulfate, mono potassium phosphate, etc… you get the point. But a fertilizer’s salinity index will give you an idea of how much burn a fertilizer can induce. Ammonia sulfate has a much higher salinity index than Calcium nitrate. Salinity index is a measure of the relationship between moisture and Electrical Conductivity. In essence, when our ground becomes too salty, the ground pulls harder on the soil moisture than the roots can pull on that same water. And as the concentration of detrimental ions like sodium climb, they will be absorbed more readily than a similar ion like potassium. And with the roots working harder, more energy is expended trying to get water up the xylem. Staying alive becomes a priority over making bigger babies.

It is also important to remember that stable salts don’t attach to the soil colloid. They can wedge the ground open to allow water to pass but they won’t displace each other. Calcium sulfate likes to be calcium sulfate. Potassium sulfate is very stable as, you guessed it, potassium sulfate. You have to break apart the salt to make the magic happen. We can help this process along in high pH soils by adding acids to our irrigation water or applying acid directly to the soil. Break apart calcium sulfate, and one calcium ion will displace two sodium ions from the attachment points. Rain water can now drive that sodium out of the root zone. Adding sulfur to the soil will help this process along in the same manner. Carbonic acid, hydronium acid, even citric, humic and fulvic acids will help. Adding more carbon and hydrogen will allow Mother Nature’s blessing of rain water do a better job of cleaning up our soils. And remember, rain water is more acidic than irrigation water…. Get the picture? The EC’s in the soil should also pull that rain water down more easily.

Turning the pumps on during the winter months can be a royal pain the gluteus maximus. But we don’t have to run full irrigation sets if we are just keeping our soils moist. Keep the soil saturated, add some acid to it and let the rain do its job. That spring time bloom will thank you for it and you may even be able to add less overall fertilizer next year and see more than adequate tissue levels. Be proactive this winter and give your soil a good scrubbing. Your trees will shine next spring with clean pipes this winter.