It’s that time of year when we’re planning preemergence (PRE), aka residual, herbicide programs for orchards,” says Brad Hanson, University of California (UC) Cooperative Extension specialist in the Department of Plant Sciences at UC Davis. “Typically these are the herbicides that are applied in the fall, winter, or early spring before weeds emerge.”

Hanson presented the topic of Weed Control for Orchard Crops during Tehama County’s inaugural Tehama Growers Meeting/Continued Education Hours Workshop in November at the Tehama District Fairgrounds.

Hanson talked about weed control in general, however, his emphasis was on PRE control.

He discussed research conducted in Hanson’s department by a former graduate student, Dr. Caio Brunharo, who is now a faculty member at Oregon State University, that focused on evaluating sequential herbicide applications in perennial cropping systems as a means to provide season long weed management; reduce postemergence herbicide use and selection pressure on summer weed species.

In a UC Davis Weed Science blog post, Brunharo said summer grass weed species are becoming more troublesome in orchards.

“Feather fingergrass, junglerice, sprangletop and threespike goosegrass, to name a few, are summer grass weed species that germinate (or in some cases, resume growing) when the soil temperatures start to rise in the spring, develop during the summer and complete their life cycle in the fall,” Brunharo wrote.

With summer grass weed species reaching their peak late summer, early fall, that timing coincidentally occurs when harvest operations are taking place.

“To make matters worse,” Brunharo says, “some of the mentioned weed species have some degree of glyphosate resistance/inherent tolerance.”

Hanson adds to this, “As most orchardists and pest control advisors are well aware, glyphosate-resistant weeds have been one of the biggest weed management challenges in California orchard crops for several years.”

In discussing this issue, Hanson said for growers in the Central Valley, “your biggest challenges in the glyphosate-resistant weed department are probably one or more of the winter annual weeds.”

In the San Joaquin Valley, hairy fleabane and horseweed (also known as mare’s tail), dominate.

In the Sacramento Valley and in some North coast areas, Hanson said annual or Italian ryegrass is more common.

“For an extra challenge, many growers have a mix of several of these, in addition to their other common orchard weed spectrum,” he added.

The Problem

Brunharo says the common weed control program in tree nut orchard crops in the state consists of a winter preemergence/postemergence herbicide tankmix application, followed by a burndown application in the spring with a postemergence herbicide, and then an additional burndown herbicide application before harvest in almonds.

“However,” he says, “because most of the burndown herbicides have no residual activity (such as glyphosate, glufosinate, paraquat) or relatively sort residual activity (such as oxyfluorfen), weeds that germinate after the spring treatment may still develop during the summer.”

In addition, in the summertime, the weeds will grow larger and become less prone to control either because of their size or because of resistance to common summer POST herbicides, Brunharo explains.

“In this context,” he wrote, “season-long weed management strategies become crucial to prevent weeds from interfering with irrigation systems or harvest operations in orchard crops in California.”

Field Trials

Hanson’s team looked at the concept of using sequential PRE herbicide programs in tree nuts as a way of specifically targeting summer emerging weeds.

“The idea behind the sequential approach is to apply a second PRE herbicide shortly before germination of the summer species rather than trying to achieve summer weed control with only the PRE herbicides applied in winter,” Brunharo said.

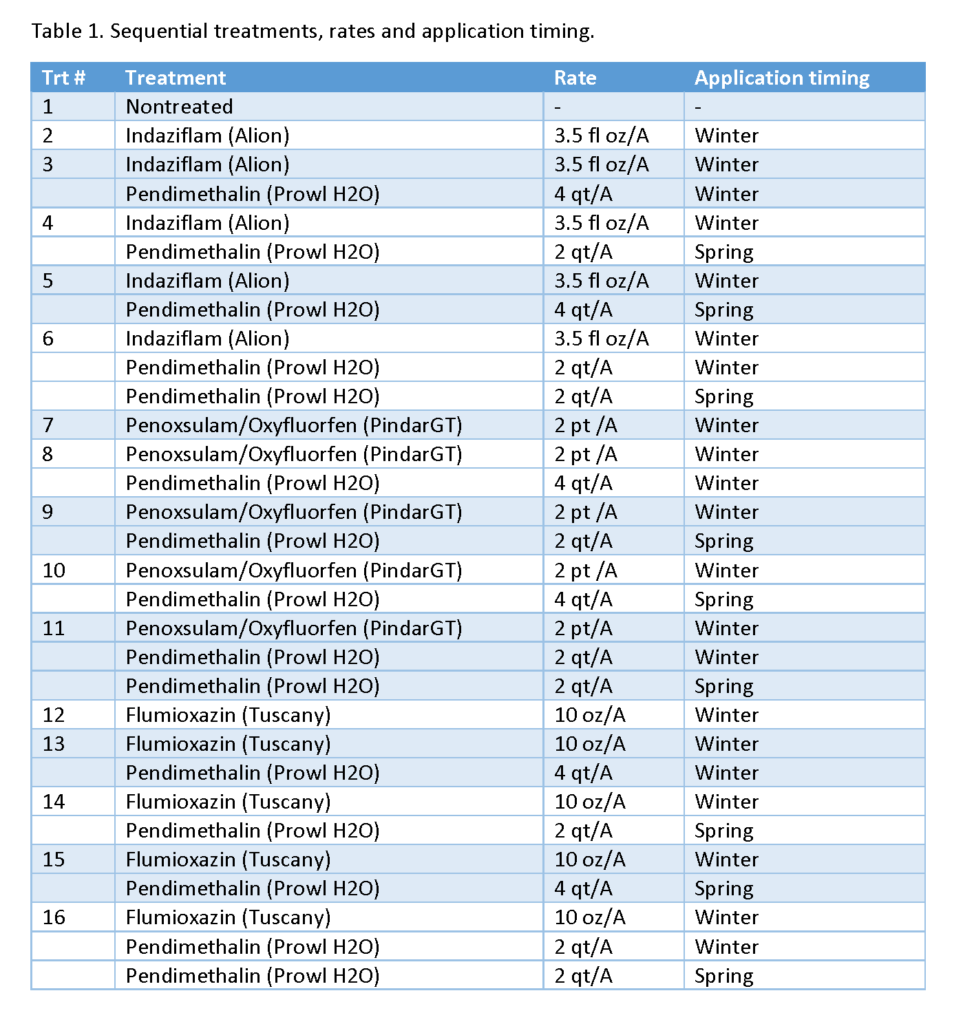

Two field trials were conducted in walnuts in Tulare County from December 2017 to August 2018. The treatments consisted of a December application of one of three common preemergence herbicides. On top of this, pendimethalin (Prowl H2O) was tank mixed with the December treatment, applied as a sequential treatment in March, or split with part of the pendimethalin treatment applied in December and part in March. (see table). The foundation herbicides were indaziflam (Alion), penoxsulam/oxyfluorfen (PindarGT) and flumioxazin (Tuscany). At both application timings, glyphosate + glufosinate was added to the preemergence treatments to ensure that all weeds evaluated originated from seed and not from regrowth. Junglerice was the predominant summer weed species at both sites. Junglerice control was evaluated monthly and aboveground biomass was collected in August before trial termination.

Brunharo said both sites yielded similar results.

“We observed a general trend that the addition of pendimethalin enhanced jungle rice control throughout the crop growing season. Not surprisingly, summer grass control was best with all three winter foundation herbicides when followed with the high rate of pendimethalin (Prowl 4 qt/A) in the spring,” he added. “In areas where summer weed species are the major issue, shifting some or all of the pendimethalin component of the herbicide program may significantly improve performance relative to the winter-only PRE approach. However, in areas where winter grass weed species are also troublesome, the sequential pendimethalin application may be more appropriate.”

Brunharo said the bottom line is that we can, in some instances, improve or maintain weed control outcomes using less herbicide by carefully considering the biology of the weed, weed control goals, and the weed management tools at a grower’s disposal.

Herbicide Dissipation

Hanson discussed five concepts concerning herbicide dissipation (or disappearance), which he said is a word that describes both degradation processes and transfer processes.

Hanson explained that all herbicides dissipate in the soil environment and that this usually follows what is called first order or second order degradation kinetics—basically a curved line.

“This means that the processes happen faster at first and then slow down over time,” he added. “The whole point of residual herbicides is that they persist in the soil for a period of time and affect weeds that germinate after the application.”

The five concepts are as follows:

Herbicide dissipation is the function of both degradation and transfer processes. Degradation implies a change in structure and transfer implies and change in availability.

PRE herbicides have some thresholds for weed control efficacy and varies among weeds and herbicides. Duration of weed control is greatly affected by degradation rate. Degradation rate is a function of both the chemistry of the herbicide and environmental factors.

Duration of a single application of PRE herbicide applied in late fall is largely a function of starting concentration and degradation rate. Higher rates typically result in longer weed control. A higher rate will remain above the activity threshold for longer than a lower rate of the same herbicide.

Hanson said, to him, one of the biggest challenges of using PRE herbicides in the orchard system is that growers typically apply PRE herbicides in the winter when they get rainfall to incorporate them, but the herbicides may dissipate too fast to control the late winter weeds or the summer-emerging weeds.

“Starting with higher application rates in the winter is one approach to addressing this issue,” he explained.

A PRE tank mixture broadens weed control spectrum and can be good for resistance management but does not necessarily affect duration of weed control because degradation rate is largely independent for the two herbicides.

“Oftentimes, we’ll use a tank mix of two or more PRE herbicides in the winter to broaden the weed control spectrum and reduce selection pressure for herbicide resistant weeds,” Hanson stated. “While this is a good approach to managing diverse weeds, it does not really do much to stretch the weed control duration later into the summer because the dissipation processes of the individual herbicides are really independent of one another.”

A sequential application with another residual herbicide (plus a POST partner) may extend weed control in some cases without significantly increasing total herbicide used.

“Sequential applications of PRE herbicides is another way that weed control duration might be extended later into the season,” Hanson says. “This could be a sequence to two different herbicides with the first PRE herbicide applied in winter and the second PRE herbicide applied in late spring. This might also be done with a repeat application of the first herbicide which could make sense in some situations, and another to target summer grasses.”

In summary, Hanson says how do you typically account for dissipation of PRE herbicides in orchard crops?

He shares three general strategies:

Use mixtures of more than one PRE herbicide.

Apply a higher (labeled) rate of PRE herbicide.

Use a sequential approach to PRE programs in orchards.

To illustrate this strategy, Hanson shared the following:

“An almond grower who typically uses an effective preemergence program applied around the first of December followed by a March ‘cleanup’ treatment with glyphosate may still have difficulty managing glyphosate-resistant grasses. The grower knows that herbicides like oryzalin or pendimethalin could help with grasses. Using the higher rate approach, the grower could use a high label rate one of these materials in December with the idea that it will persist long enough to control summer grasses emerging six months later. Using the sequential approach, the grower could move all or part of the oryzalin or pendimethalin component of the program to March timing to more directly target those summer germinating grasses, possibly at the same or even lower total application rate.”

Hanson says one of the main points of this work is that more herbicide is not necessarily the best way to get good weed control in orchard crops.

“I’d rather see growers and PCAs consider the specific weed control challenges in an orchard, and evaluate how best to use the weed control tools at their disposal. Thoughtful, but not excessive, use of our herbicide tools can save money, reduce environmental impacts and result in better weed control. That’s the goal here.”