Young walnut trees, like young children, need to be trained, and if not trained correctly, the outcome could be much less than desirable.

One of the goals of walnut tree training, according to Janine Hasey, UCCE farm advisor emeritus, is to create a final tree structure that is capable of bearing heavy yields and maintaining productive fruitwood. In addition, early cropping, reduced breakage, allowing ease of moving equipment through orchards and filling the space allotted to the grower are among the desired outcomes.

In a presentation on walnut tree training using the no pruning/no heading approach, Hasey said growers have several training options to choose from, however, with each option comes more decision making. And the options are multiplying as more and more information is provided through studies and research on training and pruning practices.

Hasey said training young walnut trees occurs in years 1 to 6 in the life of an orchard.

“The traditional method of training has involved using a modified central leader with minimum pruning method. This method has been used for decades,” she added. “That is with the traditional headed trunk and headed scaffolds in the training stage. I had recommended this method for the past 28 years.”

In an article Hasey wrote on the subject, she stated, “We believed for decades that if lateral bearing walnuts (most of our varieties) were not pruned, their growth would stall out from early cropping.”

However, research conducted over more than a decade by Hasey, UC Davis Extension Specialist Bruce Lampinen, and Katherine Jarvis Shean, UCCE orchard advisor, Sacramento/Solano/Yolo counties, has given growers the no pruning/no heading method to consider as a training option, along with variations of the unpruned method.

“Results from trials on several walnut varieties, including Howard, Chandler, Tulare, Forde, Solano and Livermore, have shown young walnuts do not need to be pruned in order to keep them growing or to produce adequate yields,” Hasey said.

In addition, the no pruning/no heading method saves on labor costs and reduces opportunity for disease and pests.

No Pruning/No Heading

Hasey explained that when she talks about “no pruning,” it means no heading and limited thinning.

“Obviously you are going to have to thin some branches on the lower tree. You have to take off the lower branches for shaker operations and branches that are a safety hazard for ease of maintenance,” she said. “Also, a single trunk at first dormant must be selected.”

Training starts at first dormant pruning, assuming trunk development only during first leaf, which is what takes place in 99 percent of walnut orchards.

Training 101

At first leave training works to develop the trunk, Hasey said. “In the first dormant, at year one, that is when you either head the trunk, or you don’t head. If you choose to not head, leave the leader unheaded. Ten to 12 feet of growth is desirable.”

It is in the second leaf that the primary scaffolds are developed on the tree. The second dormant is when the grower either heads the primary in minimum pruning, or opts for not heading the primary in the unpruned/unheaded system. Remove branches below 4 to 5 feet (3 to 4 feet for hedgerows).

“In the third leaf, the secondary scaffolds are developing. In the no-head systems, the tree is developing short shoots or spurs during that time and you may see some extension growth,” Hasey added.

At the tree’s third dormant, in minimum pruning, the secondary is headed, or in the no-heading method the secondary is left alone, and the only pruning is for orchard access and disease management.

“Unpruned trees tend to grow as a central leader with the primary branches naturally well-spaced along the trunk and at wide angles,” Hasey explains.

For fourth leaf, the tertiary scaffolds are developing and with no prune orchards, she said that is when growers see a lot of extension growth. At fourth dormant, again the option for minimum pruning is to head the tertiary or in the no-pruning method, don’t head the tertiary.

Pruning Trial Results on Varieties

The research on the Howard started at first dormant and went through year eight for Howard and seven for Chandler. This trial was by Lampinen and took place at the Nickels Soil Lab in Arbuckle. It started in the second growing season comparing pruned to no pruning methods.

“With the Howard, after seven years of pruning treatments we saw no benefits to pruning compared to unpruned,” Hasey said. “The comparable yield was exactly the same.”

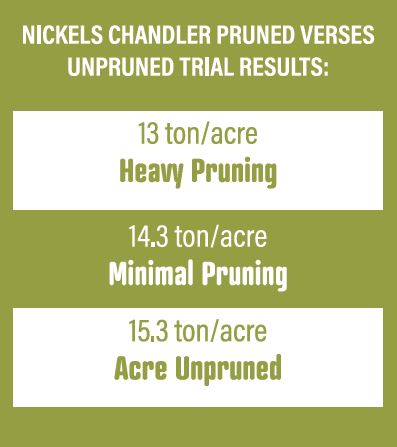

The Chandler orchard was planted in hedgerow in 2008, class 2-3 soil. The trial’s first pruning treatments in March 2009 were: Heavily pruned (Hasey does not recommend this method), minimally pruned (what has for decades has been the traditional method), and unpruned/unheaded. In all methods the lower limbs below 3 feet were removed.

“I recommend removing necked buds. Primary buds more than 5 feet from the ground that are necked and have a viable secondary bud below it should be rubbed off to the side so as not to damage the secondary bud,” Hasey said.

She also recommends the use of tall stakes or extension for unpruned/unheaded trees.

“Use tall stakes at planting or apply extensions by first dormant before second leaf. Stakes are not always needed; it depends on wind conditions where the orchard is located and on trunk growth. Always tie trees to the stakes loosely,” Hasey said.

During the trial, researchers learned in the third year that minimally pruned trees needed 10 inches more water than the unpruned trees, and from the second to fourth leaf on all pruning methods, the yield on the unpruned trees was greater than the other methods with the trend continuing through the seventh leaf. The difference was especially significant between the heavily pruned trees compared to the unpruned trees.

Regarding walnut quality of the different pruning methods, in 2013 there was significantly more shrivel in the minimum pruned orchard crop compared to the unpruned trees. In years 2014 and 2015, there were no significant differences in quality, Hasey said.

In summarizing the Chandler pruning trial, Hasey said the heavy pruning method resulted in smaller trees and lower yield in years two and three. After seven years, the cumulative yields were not significantly different for any pruning treatment, but the unpruned/unheaded trees did trend higher. In addition, water use efficiency was higher in the unpruned/unheaded orchard.

“We saw no benefits to either minimum or heavy pruning in this trial,” she added.

Statewide Walnut Training Trials

There is a total of 14 ongoing trials in California comparing pruned to unpruned/unheaded training methods on Chandler, Howard, Forde, Solano, Tulare and Livermore varieties from Butte to Tulare and Kings counties, Lake and Contra Costa counties.

The trials are researching variations of the unpruned/unheaded method, Hasey said.

What researchers have learned so far is that during the orchard development phase, advantages to unpruned/unheaded training include early increased yield, crop distributed over more primary scaffolds, less limb breakage in years five-seven, and trends toward better nut quality.

“We found some of the disadvantages to pruning are the costs of labor to prune and dispose of prunings, more scaffold breakage in years after pruning stops, lower canopy shades more rapidly which leads to quality problems, and pruning wounds exposed the tree to botryosphaeria infection,” Hasey added.

She says that the statewide pruned versus unpruned/unheaded trails, along with grower trials and experiences, just don’t support the common idea of pruning and heading lateral bearing walnuts is needed for growth and productivity.

“This is a major paradigm shift in walnut training. Growers now have more viable options available to them than just minimal pruning,” Hasey said.