There are limited numbers of pesticides coming down the pike, so preventing resistance and stretching the pesticides currently in the toolbox is critically important. Biological control can be a good solution, particularly if it reduces the number of sprays in a given season.

Emily Symmes, UCCE Sacramento Valley Area IPM Advisor, said there are several things growers should know when working with beneficials in their orchards:

Trapping and Monitoring

“An acute understanding of the natural enemy lifecycle is important,” Symmes continued.

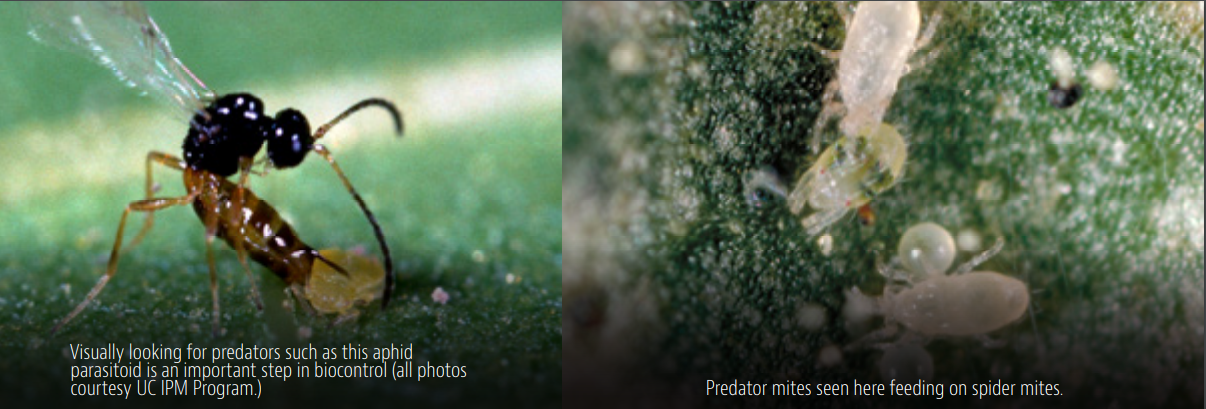

This can be done by monitoring for predators and parasitoid activity. In almonds and walnuts this has historically been more of a visual observation system, Symmes said.

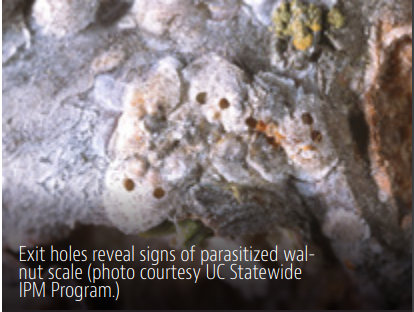

“For example, with scale pests in walnut or almond, you’d be looking at the scales themselves. You’d be looking at evidence of parasitization, meaning the exit holes where the parasitoid has emerged or whether they have the visual appearance of being parasitized, which can appear as darkening in the nymphal stages,” Symmes said, adding this is also a similar method for monitoring aphids.

In the past, searching for spider mite natural enemies (predator mites and sixspotted thrips) has been done by looking at the undersides of leaves. This has changed in recent years for sixspotted thrips, as Symmes and UCCE Kern County Farm Advisor David Haviland conducted work on a sticky card method for evaluating sixspotted thrips populations.

Haviland’s research was in the south part of the Central Valley and Symmes in the north. They hung sticky cards in the orchard to monitor for thrips and determine their numbers in the orchard and when they were most active.

Haviland has developed thresholds for almond orchards in the south and Symmes is working to validate thresholds in the north and determine thresholds for walnuts as well. These thresholds will help guide growers in making treatment decisions that minimize damage while preserving beneficials.

“It’s a measure of how much spider mite pressure you have, how many spider mites you’re seeing on the leaves, plus predator mites on the leaves as well as this card-based monitoring method for sixspotted thrips,” Symmes said.

Haviland was expecting to complete a three-minute video on employing the card-based threshold system for spider mites and sixspotted thrips in April and publish it on the almond page in the IPM guidelines, Symmes said.

Symmes typically places about three yellow cards per block. She currently advises growers to place one or two traps in known mite hotspots and one or two internally in the orchard to monitor non-hotspots.

“We have basically put them where we would get out of the truck and do our leaf sample evaluations for mites, and/or where we already have our trapping stations set up for other pests like navel orangeworm” she said. “And again, it’s detection—are they there, are they not.”

Symmes said the thrips monitoring cards are available from Great Lakes IPM and Trécé.

Protecting the Beneficials

The first step is to protect what’s already in the orchard, then finding out when a predator or beneficial is most effective against a targeted pest. This information is necessary so that the beneficials are protected whenever a spray application is made for any pest, and not necessarily just the targeted pest.

For example, some spray applications made for navel orangeworm (NOW) can cause a secondary problem by impacting predators and causing spider mite populations to build up to far greater numbers, Symmes said. This makes it important to consider the impact of the sprays being applied, and what the consequences are on that particular natural enemy. At the bottom of each pest management guideline on the University of California Statewide Integrated Pest Management Program (http://www2.ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/), a link summarizing the impacts of commonly-used pesticides on natural enemies and pollinators is available.

“That’s a good starting point to choose a particular pesticide that might have the least impact on the natural enemies in the system,” Symmes said.

Timing for applying certain pesticides is important, too. “If it’s a time when the natural enemies aren’t terribly active that can be a way to avoid particular damage to the natural enemy population,” Symmes said.

“Depending on the pest, if you can do an environmentally safe dormant application, sometimes that’s better than later season with regard to protecting natural enamines,” Symmes said.

Timing Spray Applications

Applying spray applications for pests while protecting the beneficials can be challenging, Symmes said. For instance, trying to protect predator mites while treating for spider mites can be tricky, as miticide modes of action, even if selective, may impact both the “good mites” and the “bad mites.”

In addition, “Sixspotted thrips are extremely susceptible to pyrethroids and abamectin, which may be used in almonds and walnuts to control worms and spider mites,” Symmes said. “Sixspotted thrips populations can be completely wiped out, particularly with ‘May sprays’, at the exact time of year when you want them to be building up to keep pace with your spider mites.”

“Sixspotted thrips is a really good predator of spider mites and spider mite eggs, and it’s really quite abundant if protected properly in the almond system, and actually I’m seeing it quite a bit in the walnut system as well,” Symmes said.

Most pest control advisors Symmes has been in contact with plan to start monitoring for sixspotted thrips in their orchards using the card-based method, which is more reliable and efficient than the older method of looking for them on the undersides of leaves. “That’s amazing to have some new information come out and see it almost 100-percent adopted by folks really wanting to track those populations and make decisions based on biocontrol,” she said.

Symmes’ take-home message on spray applications is: If sixspotted thrips are working in the orchard, avoid early season preventative applications of abamectin for spider mites and avoid spring pyrethroid sprays for NOW.

Beneficial Successes

There are several beneficials in almonds thanks to changes in how growers have managed the balance between beneficials and pests in recent years.

“San Jose scale has great parasitoids, and honestly, San Jose scale is not a problem in almonds anymore,” Symmes said.

The transition away from many of the in-season broad-spectrum pesticides has allowed the parasitoids to manage San Jose scale. Currently, Symmes advises monitoring parasitoid activity and treat only when there isn’t parasitoid activity in the orchard.

Walnuts have walnut scale and frosted scale, and they both have some good parasitoids. Several years ago, there was an increase in these species, and a lot of orchards required treatment for one or both species. In Symmes research and observations, she saw a significant amount parasitoid activity rebound in walnut scale over the last few years.

As a result, growers may not need to treat every year. Instead, a treatment may only be needed every two to four years to knock down populations.

“This allows that parasitoid population to build up,” Symmes said.

Aphids appear to have good parasitization in walnuts, but walnut husk fly, in comparison, has nothing. Codling moth has an egg parasitoid, but it doesn’t consistently appear to have a huge impact, Symmes said. Navel orangeworm, a continual pest in almonds and walnuts, has a couple of parasitoids that lay their eggs and kill the larval stages, but they don’t typically occur naturally in large numbers. One of them, Goniozus legneri, can be purchased and released, Symmes said.

More research on releases of parasitoids for NOW is needed, she noted.

“[We should be] looking at new release mechanisms like drone release and different things like that to see if we can actually get some increase of parasitization for navel orangeworm. We haven’t researched this aspect of NOW management in recent years, and don’t necessarily know the impacts of our current chemical practices on NOW parasitoids.

“Again, it goes back to know what’s there, know what effect whatever material you’re putting out in the orchard might have on them, try to protect them, try to leave them a little bit of a food source by tolerating a little bit of a pest population. David Haviland always says the trick is, ‘don’t starve them and don’t kill them’,” Symmes said.

Beneficial Purchase and Release

An orchard system is different from a greenhouse operation where predators are purchased and released in a confined space where they can’t escape. In orchards it’s typically more about protecting the beneficials that are already there and allowing them to flourish—rather than a system of purchase and release, Symmes said.

But this may be changing, she continued. “I found out just a few weeks ago that one of the insectaries is actually producing sixspotted thrips this year for purchase and release.”

While there isn’t any data from the university, Symmes finds it, “particularly intriguing”.

“You could actually go out and release some additional predators in the orchard, especially at kind of those peak mite times of year and get some additional knockdown. So that’s something that we need some research on,” Symmes said.

Keeping Beneficials Working

The sixspotted thrips are very effective in knocking down the pest spider mites, so keeping them alive and active will help limit the number of miticides used in an orchard system, Symmes said. Sixspotted thrips thrive in dusty, webby, environments where spider mites also flourish, which makes it a very effective predator.

In order to keep beneficials active, Symmes noted that they need the pests to feed on. If they don’t have food, they will either die or go elsewhere. With mites, she said, “You’ve got to be a little bit tolerant of some spider mite pressure in your orchard.”

Almonds, and tree crops in general, Symmes continued, can withstand fairly significant pressure before there is economic damage such as reduced yield the following year, very early defoliation, etc. The key is maintaining a good balance of the pest and predator in the system that keeps the spider mites in check throughout the season, Symmes said.

Other Options

Other options for protecting beneficials include things like cover crops and hedgerows to provide supplemental resources for predators and parasitoids. This in turn can help keep them close to the orchard environment, Symmes said.

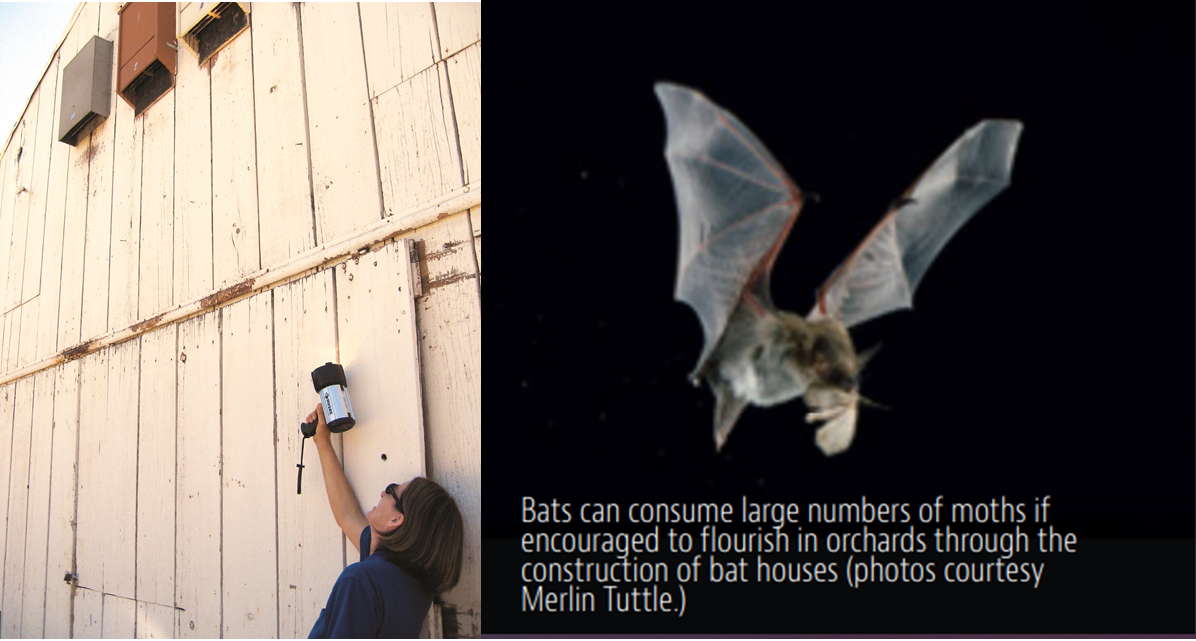

“Bats and insectivorous birds are fabulous biological control agents, and I’m always a little remiss that I don’t talk more about them,” Symmes said. Bats consume massive amounts of moths, she continued. “If you’re talking about codling moths in walnut, navel orangeworm in almond, or in walnut, or in pistachio, bats can do a tremendous service,” Symmes said, and she strongly encourages grower to build bat houses and let the bats work for them.