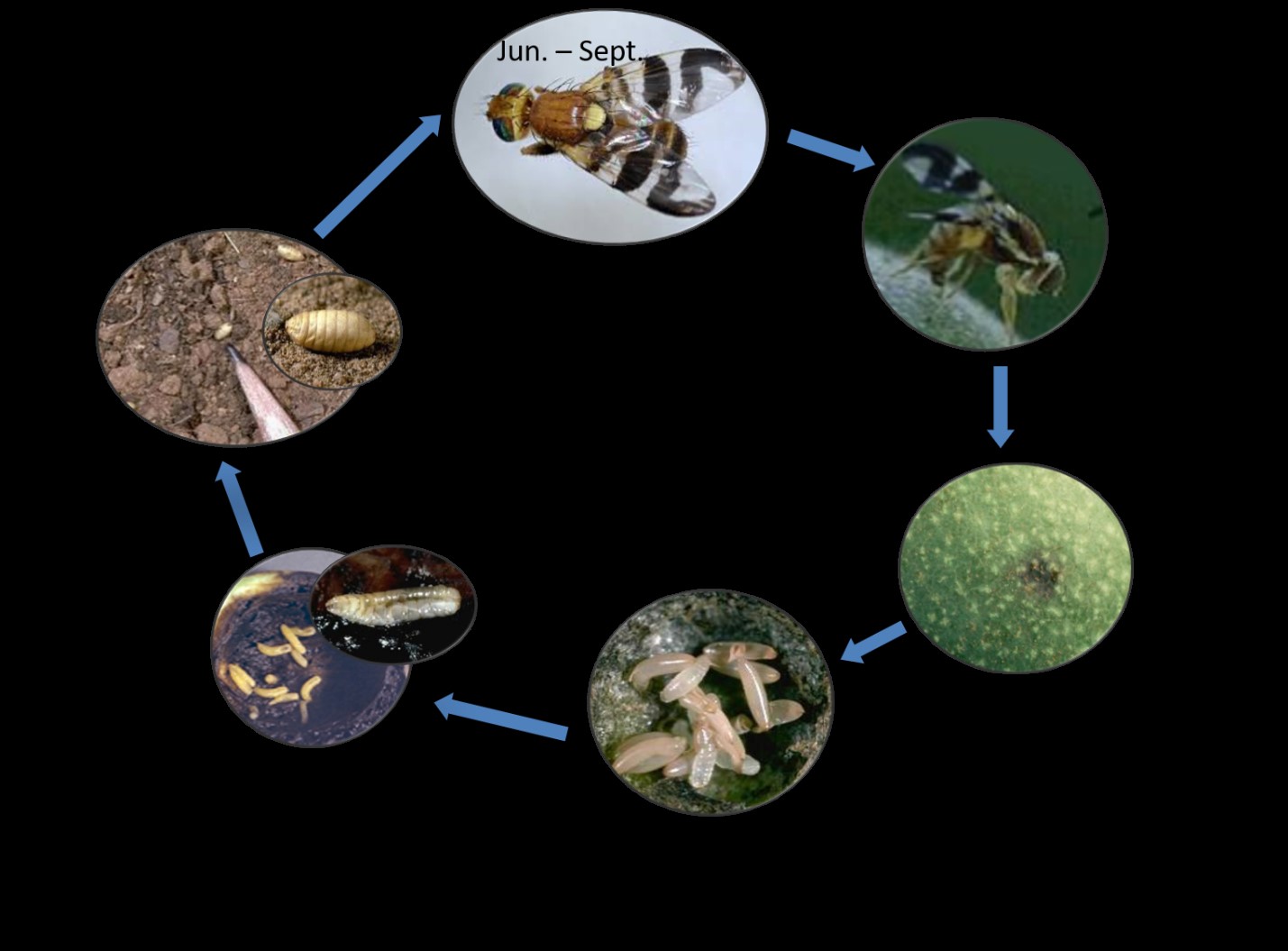

The walnut husk fly, Rhagoletis completa (Diptera: Tephritidae), is a colorful fly of about the same size as the house fly but has iridescent greenish eyes, and banded wings. Walnut husk fly adults have a yellow spot below the wing base, and a dark triangular band at the wingtip, which distinguishes the husk fly from other Tephritid flies. Walnut is the primary host of this insect, although there have been reports of an occasional attack to peach trees that are near walnuts. The walnut husk fly has been an increasing problem in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys, major walnut growing regions in California. Female flies deposit white eggs resembling rice grains, just underneath the walnut husk and the larvae (i.e., maggots) feed on the husk upon hatching within five days. The maggots continue to grow inside for the next three to five weeks, and the mature maggots drop to the ground and burrow several inches into the soil to pupate. The majority of the walnut husk fly has one generation per year, and these overwintered pupae emerge as adults the following summer—June through September in the Central Valley. Still, some may remain in the soil for two or more years. (See the complete life cycle in Figure 1.)

Nature of Damage

Larvae feed inside the husk and cannot be seen from outside; however, the presence of dark, soft blotches on maturing husks (Figure 2) indicate potential husk fly presence in the fruit. The maggots feed inside the husk, enlarging the affected fleshy part of the fruit inside, but leaving the outer skin of the husk usually intact. Early season feeding by the walnut husk fly results in shriveling and darkening of the kernels, with the increased potential for mold growth. The mid-to late-season infestation causes negligible direct damage to the kernel, but can stain the shell (Figure 3), and that reduces the marketable yield for in-shell market and also creates issues during the shelling process.

Factors Affecting Husk Fly Infestation

Although the husk fly can attack all major cultivars of walnut grown in California, the susceptibility can depend on several factors such as fruit size or other fruit morphology, such as the presence of trichome or hairs, and the maturity time of the cultivars. Based on various studies in California, the most susceptible cultivars reported are Eureka, Payne, Hartley, Serr, and Tulare. However, local environmental and ecological conditions are the major driving factors related to the husk fly infestation in walnut orchards. Husk fly damage seems to be aggregated, or patchy, in distribution with the orchards with higher infestation occurring in the cool, shady, moist part of the orchards. Orchards that are near a water body such as a river, stream, creeks and other hosts including black walnuts favor walnut husk fly infestation. Various factors that might affect the husk fly emergence timing and duration have an important effect in monitoring and managing this pest. Recent studies from Dr. Nick Mill’s lab at UC Berkeley showed that insufficient winter chilling hours during the winter results in extended and unsynchronized adult emergence in the summer. Using this new pupal recovery technique, we found that majority of the husk fly pupae (85 percent) overwinter within the top 4 inches of the soil. The knowledge about overwintering biology of this pest can be utilized to explore some alternative control options such as cultural practices that include discing to expose the pupae, use of cover crops, and potential use of soil-based entomopathogens. These are some of the areas that future research needs to be focused on.

Monitoring in June

The flies are attracted to yellow sticky traps supercharged with ammonium carbonate as they search for the nitrogen-based food source that is critical for the development of their eggs and, thereby, egg-laying capability. It is important to put these traps in the orchard at least by June 1, before the beginning of the adult emergence in the orchard. Since the patchy occurrence of the husk fly within the orchard, finding a suitable place to ensure catching flies is important. Hang the traps as high as possible on the north side of the tree under the dense foliage area and check the traps1-2 times per week. After catching flies, identify the female (light-colored first leg segment, pointed abdomen and slightly larger), and gently press the abdomen to squeeze out the content to determine the white ‘rice grain’ looking eggs (see Figure 4). Apply insecticide when the first female with eggs is found. Although monitoring the oviposition mark on the nut provides an idea about the husk fly activity in the orchard, this is the least preferred method as the eggs have already been laid inside the fruit at that point.

Timing Insecticide Sprays

Although natural enemies of the walnut husk fly may present, these are not effective in commercial walnut orchards. Current husk fly control is primarily dependent on insecticide sprays targeting the flies after emergence and before laying eggs on the fruit. The first application begins as soon as a single female fly with eggs is captured in the trap, and often requires multiple sprays depending on the time of the capture and duration of the adult emergence period. Husk flies are not a problem after the husk split, and treatments are not necessary if the harvest will occur within three weeks. All insecticides except GF-120 (already has bait mixed) should be applied with bait, which attracts adult flies. Several bait types such as Nu-Lure, Monterey, or molasses are available. Since bait is used, coverage may not be critical for low to moderate populations and spraying alternate row applications or aerial applications are also effective for those orchards. However, if the orchard has a history of heavy infestation, and trap capture indicates high pressure, full coverage with high volume sprays may be needed. Similar to other pests, consider efficacy, cost, and potential impact on natural enemies when selecting insecticides for husk fly control. Follow the UC IPM Pest Management Guidelines for walnut husk fly, for insecticide selection and other additional information go to ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/walnut/walnut-husk-fly.