Guidelines for hazelnut nutrition are currently being updated at Oregon State University (OSU). The original nutritional guidelines were largely created for dryland Barcelona – an old classic variety that is now being phased out of orchards because of its high susceptibility to Eastern Filbert Blight (EFB). With all the newer hazelnut varieties introduced by OSU, new research is underway to determine the optimal levels of fertilizer for these trees.

“We’ve been preparing for a revision of that document for a number of years now, because the information in the old hazelnut fertility guide is based on the old orchard system,” said OSU Orchard Specialist Nik Wiman.

For the past three years, OSU researchers have collected hazelnut leaf tissue samples year-round and recorded the results. They are currently studying all the data.

Tissue Test Study

Researchers are looking at critical values for tissue testing. Wiman is reluctant to talk much about it yet. “We have a ways to go,” he said. “We want to be able to link the tissue test with production level in as many orchards as possible.” The university has 20 test plots in Oregon’s mid-Willamette Valley: south to Monroe and north to Aurora “for a pretty good representation of the valley,” Wiman said.

The current parameters are for tissue tests done in August, but, Wiman said, “We think that if you can do it in June, you have more opportunity to change the course a little bit.

After the study is finished, “We may have to revise the critical values for the tissue tests,” Wiman said.

A Look at Non-structural Carbohydrates

One area of current study is the link between non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) to tree health and yield and nutrient content of tissues. This work is supported by the Oregon Hazelnut Commission and involves the Carbohydrate Observatory Laboratory at UC Davis.

The NSC in plants are a product of photosynthesis and can be stored by the tree. NSC are mainly water-soluble sugars such as glucose, and the stored forms of NSC are starches. They play an important role in how a tree responds to the environment. High levels of NSC allow a tree to better tolerate severe drought.

Since hazelnut flowering happens during the winter when the trees’ leaves have dropped, bloom, nut set and yield are likely dependent on NSC levels stored within the tree.

So, if NSC are so important to the growth and yield of nut trees, how does a grower boost these carbohydrates in their orchard? Actually, it’s not simply a matter of boosting the NSC, but also of retaining them.

“Carbohydrates are a form of carbon,” Wiman said. “Through photosynthesis the plants are fixing carbon, so anything you can do to enhance the growth of the tree is going to boost the NSC. You want to maximize the photosynthesis.”

Things you don’t want to put your trees through are, of course, drought stress or nutritional deficit. But there are other issues that will also likely reduce the amount of NSC in your trees.

“Pests could probably have some effects on NSC as well,” Wiman said. One of those pests is aphids, which pierce and suck the leaves of hazelnut trees and directly consume carbohydrates. “Aphids contribute to poor fill of nuts.”

Disease also affects the tree and its ability to boost the NSC available when it’s needed. Different factors can invite disease, including flatheaded borer damage, girdling from mice and heavy pruning cuts. The tree will divert energy (carbohydrates) to make metabolites needed for the wound response.

“Trunk damage also cuts into the vascular system of the tree and affects its ability to regulate water, which affects photosynthesis,” Wiman said.

Competition is another issue that can affect NSC and the vigor of growth and production. When trees are planted too close together and shading each other, it sets up a battle among them to reach sunlight.

Hazelnuts flower during the winter. “If you think of the timing of the bloom, the tree has to rely completely on stored energy reserves because there is no active photosynthesis during winter,” Wiman said. “It’s pulling from the reserves.”

Assisting NSC Production with Nutrition

Growers sometimes overfertilize hazelnuts. Too much of a good thing is no longer a positive. Besides causing nitrates to leach into the groundwater, excessive fertilizer applications don’t help improve growth and yield, so it becomes a wasted cost. Studies show that trees take up nutrients more efficiently with lower rates of fertilizer (Figure 1).

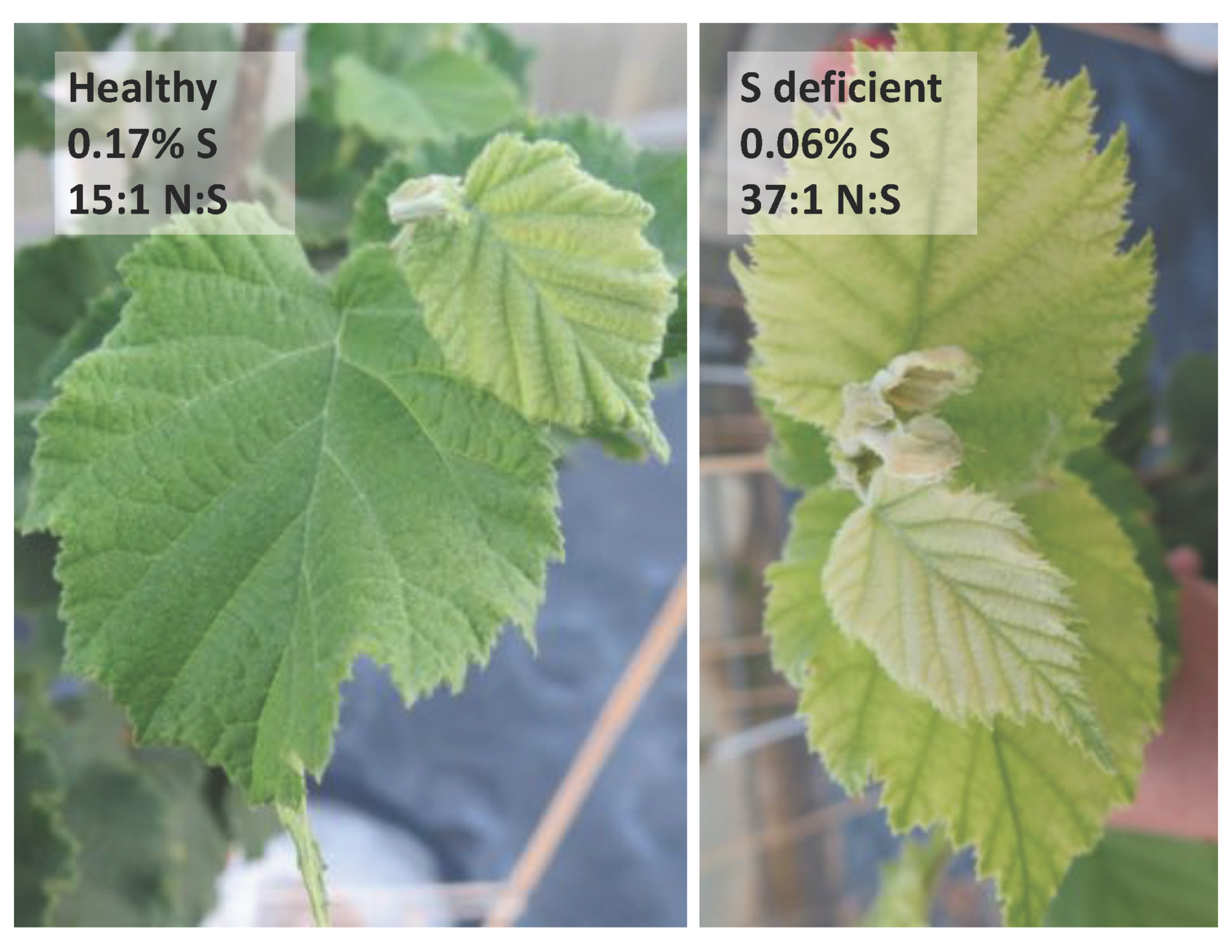

OSU studies have found that trees which received a fertilizer blend of nitrogen (urea), phosphorus, potassium and magnesium had a little faster growth rate with better uptake of nutrients compared to trees that received only nitrogen. Feeding hazelnut trees with only urea caused excessive nitrogen to sulfur ratios, which leads to poorer growth and symptoms of a sulfur deficiency. If new leaves are yellowing, growers can apply a foliar application of elemental sulfur. Or, if it meets other orchard fertilizer needs, with ammonium sulfate or potassium sulfate applied to the soil.

More Fertilizer Advice from OSU

For young trees: Take a soil sample before new plantings to access pH and evaluate the need for lime and incorporating pre-plant nutrients such as K and Mg. Don’t add fertilizer to the planting hole, especially urea, which can burn young trees. Even slow-release fertilizers can burn if they are highly concentrated around the roots.

Apply a fertilizer blend to young trees. Add a top dressing of sawdust. Better yet, apply a dressing of compost.

“In that case, you don’t need to use fertilizer,” Wiman said. “We’ve found that clean and finished compost works really well. It has bigger chunks that don’t break down as fast, but the main body of the compost breaks down pretty fast and nurtures young trees.”

Tissue tests are still a reliable measure of fertilizer needs.

When you do apply fertilizer, “We like to see the sulfur go on with that nitrogen – a slow-release blend,” Wiman said.

Too much nitrogen causes weak and lanky growth. Excess nitrogen is also an invitation to aphids, Wiman said. Nitrogen is a building block for protein. Aphids need that in their diet, so they thrive on leaves that are high in nitrogen.

Dryland trees don’t take up much nitrogen past June. For older trees: Apply nitrogen carefully in the spring after active tree growth begins. “Not overdone to maximize uptake efficiency,” Wiman cautions.

Deciduous trees suck nutrients out of the leaves and back into the woody parts of the plant before leaf drop in fall. If needed, apply a band of potash after harvest. Shred pruned branches to add carbon back into the soil.

Looking Even Closer at Nitrogen

OSU is currently tracking a stable isotope of nitrogen in a few select trees under different irrigation regimes in an Oregon Department of Agriculture Fertilizer Program supported grant that includes UC Davis based cooperator Sat Darshan Khalsa.

Most N on earth is the form of N14 (7 protons + 7 neutrons = mass number 14). Researchers generally use Nitrogen-15 (7 protons + 8 neutrons = mass number 15) as a tracer, Wiman explained.

“By applying urea fertilizer in the rare isotopic N15 form, you can follow it up through the tree after uptake by the roots and see how long it takes to move into different structures in the tree. It also gives an idea of the partitioning of how it’s moving. We already know that a lot of ground-applied nitrogen goes to the main framework of the tree before it makes it to peripheral tissues, such as leaves and nuts in successive seasons,” he said. “Part of our goal is to see how irrigation affects the uptake and partitioning.”

To trace the nitrogen, researchers cut off parts of the tree during different times of the season and send the samples to an isotope lab at UC Davis.

“Nitrogen is sort of like a bank account,” Wiman said. “If you’re not providing enough for the tree, you’ll be at a deficit at some point in the future. At harvest, how much is it taking nitrogen away from the tree? You’d better understand how the budget works.”