Recent UC research confirmed work done in the mid-1970s that timely sweeping and pickup after shaking helps reduce the incidence of moldy walnut kernels.

But the studies conducted in 2019 and 2020 led by Themis Michailides, a UC Davis professor of plant pathology based at the Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center, also identified major causal fungal agents that differ from earlier work by others.

In addition, preliminary results from his research found a fungicide treatment around hull split significantly reduced mold in walnut kernels compared to untreated checks.

“This is some new information for the growers to follow if they have a history of high mold in their orchards,” he said.

This season Michailides plans to repeat field trials designed to fine-tune fungicide spray timing and number of applications.

He presented the results of current research, funded by the California Walnut Board, during West Coast Nut magazine’s recent 2021 California Walnut Conference.

Harvest and Pick Up Quickly

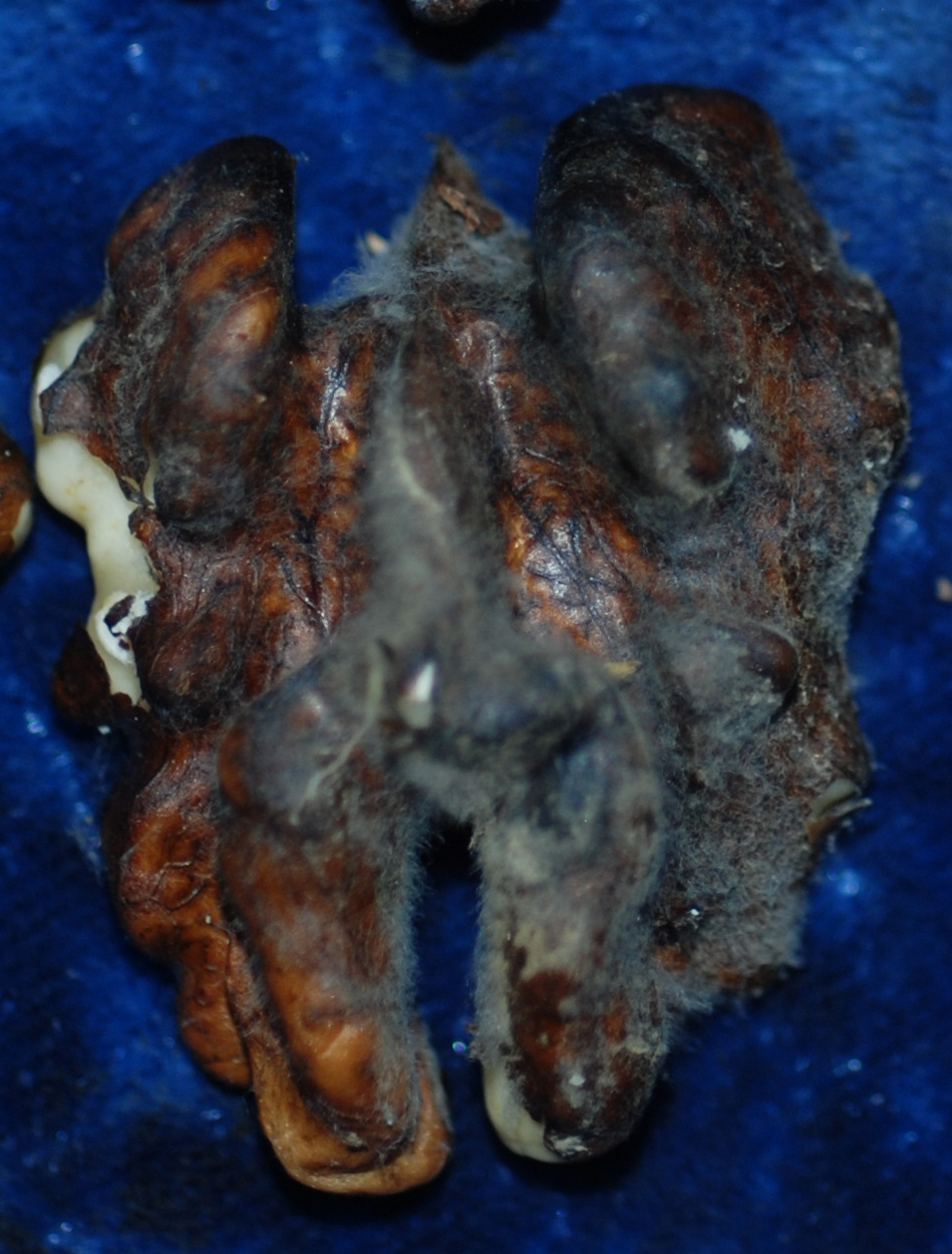

Walnut mold, which the U.S. Grade Standards for in-shell walnuts defines as decay or obvious decomposition of the kernel, is nothing new to the industry. In 1976, Bill Olson, UCCE farm advisor emeritus in Butte County, showed walnuts held on trees past optimum harvest timing or on the ground for 12 days had significantly more mold than those harvested and removed promptly. His work was the basis for current cultural practices of shaking, sweeping and pick-up as soon as possible afterward for delivery to the dryers.

Nevertheless, walnut mold continues to trouble growers, depending on the season and the presence of conducive conditions. In 2018, for example, Northern California farm advisors reported up to 40% mold in walnut orchards. In 2019, it ranged from 10% to 20%. And in 2020, grade sheets showed mold averaged 5% to 6%, with some orchards along the Sacramento River reporting as high as 16% mold.

Jake Samuel, who farms walnuts with his family near Linden, blamed rain and rain delays during the 2018 harvest for mold levels double their average. Mold rejects returned to low levels in 2019, and 2020’s harvest conditions were nearly ideal for timely shaking and pickup, he said.

“We grow predominately Chandlers, and [mold] is not necessarily prevalent in Chandlers, but it can be if there are heavy rains at harvest,” Samuel said.

Together with his brothers, he also runs a custom harvest business, and they are always under pressure to harvest in a timely manner to preserve kernel quality.

“When you’re on time with the nut harvest, on time with hull split and nut drop, you’re less apt to have mold and you’ll harvest a cleaner crop,” he said.

Contributors to Moldy Kernels

Work by Michailides and his group has shed new light on research conducted in 1979 that found fungal colonization of walnut hulls did not contribute to moldy kernels. Just the opposite is true, he said, citing some of his recent work.

In addition, research he and Mark Doster conducted in 1994-95 found a number of contributors to moldy kernels: damage from navel orangeworm and other insects, sunburned nuts, shriveled husks, nuts with larger openings at the stem, larger-sized nuts and nuts on the ground for 15 or more days after harvest. The latter backed up Olson’s 1976 research.

Samuel said he has noticed similar situations in their orchards. In years with heavy sunburn, insect damage is greater, and the two tend to lead to increased kernel mold.

Michailides’ most recent work also found secondary walnut blight infections that do not penetrate the kernel or result in nut drop can still create an entryway for pests, including Fusarium and Alternaria mold species. Known as brown apical necrosis, or BAN, these black blighted legions begin at the apical end of the fruit.

As the fungal colonization progresses, the lesions turn brown and the fungal infection expands under the hull, decaying the hull. Eventually, the infection spreads to the kernel most likely through the stem end opening.

New Studies, New Insights

Beginning in 2019, Michailides led a wide-ranging project funded by the Walnut Board to identify the causal organisms of walnut mold, determine how and when mold developed and, ultimately, develop management methods.

Initially, he tested samples from various varieties from orchards in Kern County north to Butte County to determine the most prevalent fungal species that caused mold in kernels.

Alternaria alternata, Aspergillus niger and Fusarium species were by far the most prevalent. The findings differed from 1980 research that found Penicillium accounted for up to 70% of mold in kernels. Today, it’s a minor player.

In orchards with Botryosphaeria/Phomopsis, Michailides said they also frequently found those organisms causing mold in kernels.

But does the presence of fungal organisms on the hull correlate to moldy kernels? He sought to answer the questions by conducting a systematic study in two Chandler and one Ivanhoe orchard.

“We found out with only one exception − Aspergillus niger that was present in the kernels but not present in hulls possibly due to contamination − in all of the other samples, whatever we get on the hulls, we get on the kernels,” he said. “It is not surprising that the same fungi we isolate from the hulls were also found attacking the kernel causing mold. This is very important information because since these fungi occur on the hulls, if sprays were effective in reducing hull colonizers, they would then reduce kernel mold. And this is actually the basis of why we went into the management with protective fungicides.”

Based on previous research he led on Botryosphaeria/Phomopsis, Michailides said fungicide sprays made in mid-May, mid-June and mid-July – regardless of the chemical – significantly reduced Botryosphaeria organisms in the black and brown kernels. But the sprays did nothing to reduce kernel mold caused by Alternaria and Fusarium.

Hull Split Treatments

Subsequent studies where walnuts on trees were inoculated with Alternaria and Fusarium in August, September and October found only the October timing resulted in significantly more decay.

That led Michailides to examine whether fungicide treatments around hull split might be effective.

In 2019, they looked at five treatments in an Ivanhoe variety orchard in Tulare County: 6.5 fluid ounces Merivon per acre three weeks before hull split, Merivon two weeks before hull split, 7 fluid ounces Rhyme per acre at 20% to 30% hull split, Merivon at three weeks before hull split followed by Rhyme at 20% to 30% hull split and an untreated check.

Rhyme, which contains the active ingredient flutriafol, is a Fungicide Resistance Action Committee Group 3 from FMC. It carries a two-week pre-harvest interval.

Merivon Xemium brand fungicide is a premix of the active ingredients fluxapyroxad and pyraclostrobin (FRAC Group 7 and 11, respectively) from BASF.

The treatments, except for the one two weeks before hull split, reduced mold 35% to 75% compared to the untreated check. The untreated plots had 45% mold in kernels.

“At least it’s a good indication that these types of sprays before hull split or at early hull split will have an effect in reducing mold in walnuts,” Michailides said.

He repeated the trial in the same orchard in 2020. The treatments were Merivon + tebuconazole at three weeks before hull split, Rhyme at 20% to 30% hull split, Merivon + tebuconazole at three weeks before hull split followed by Rhyme at 20% to 30% hull split and an untreated check.

In the untreated plot, 33% of the kernels had mold. A single spray either three weeks before hull split or at 20% to 30% hull split reduced mold incidence 18% to 24%. Two sprays resulted in a 45% mold reduction.

When they examined the nuts for the presence of mycelia − vegetative part of fungus consisting of a mass of branching, thread-like hyphae − the reductions were even greater. The untreated check had 37% mold. A single spray resulted in a 26% to 36% reduction, whereas two sprays yielded a 71% reduction.

A trial in a Butte County Chandler in 2020 looked at the best timing for applications of Rhyme, which has a short two-week pre-harvest interval. Treatments included three weeks before hull split, one week before hull split, 20% to 30% hull split and two different combination treatments.

None of the fungicidal treatments were significantly different, but all were numerically better than the untreated check. He plans to repeat the trial this season.

“We didn’t find the actual best time to spray, but we know September shows a good trend that reduction of mold will be achieved.”

The results mirror other trials conducted in Chandler and Ivanhoe varieties with different fungicide timings.

“Sprays three weeks before hull split and early hull split reduced walnut mold in both early and late walnut cultivars,” Michailides said.