The good news for California tree nut producers is the brown marmorated stink bug is not widespread in commercial production areas. The bad news is, where it has shown up, crop damage can be severe.

In one instance, in responding to a call from a grower in Stanislaus County, UCCE Farm Advisor Jhalendra Rijal said he was shocked to see the damage.

“It looked like somebody came through with a shaker and shook these trees on the borders,” Rijal said. “All these almonds were on the ground like a blanket.”

Later on, at harvest, Rijal said the orchard suffered losses approaching 30 percent. “It was mostly on the outside rows,” Rijal said, “but the other rows were affected, as well.”

The brown marmorated stink bug, or BMSB, is an active hitchhiker, having made its way from Pennsylvania, where it was first discovered in the U.S. in 1998, to the West Coast by the early 2000s. And it is a voracious feeder with a host range of approximately 170 known plants. The pest was discovered in California in 2006. Until just recently, it was almost solely concentrated in urban areas.

Making its Way into Nut Crops

Researchers first documented it in a commercial crop in 2016, when they found it in a peach orchard in northern San Joaquin Valley. It now has migrated to other commercial crops, including almonds.

Rijal’s discovery of it in the Stanislaus County almond orchard came in 2017. Since then, BMSB has spread steadily, if slowly, into other Stanislaus and Merced county almond orchards. “In 2018 and 2019, several almond orchards had BMSB damage,” Rijal said.

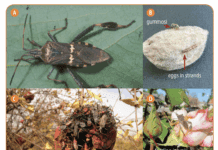

Rijal believes the early season feeding, particularly through April, is the most damaging, as small nutlets are highly susceptible to drop. Feeding damage after May has less effect on nut drop, he said, but mid-to late-season feeding on the nuts results in damaged and gummy kernels.

Depending on the temperature and the year, the pest can migrate into almond orchards from overwintering sites as early as mid-March and can feed on nuts from that point through harvest, Rijal said.

“I have seen a lot of nut drop from that early season damage,” Rijal said, “especially on the couple of rows on the border near potential overwintering sites or alternate host trees, like the Tree of Heaven. That tree is a magnet for BMSB. I’ve seen almond orchards where there is a Tree of Heaven nearby, and those orchards were hammered by BMSB throughout the season.”

Other overwintering host sites can include houses, barns and wood piles – essentially anywhere the BMSB can find warmth during winter. Orchards close to overwintering shelters or near riparian or urban areas are at a higher risk than orchards situated far from overwintering shelters, Rijal said.

Steps to Mitigate Damage

Where growers can remove overwintering host sites, Rijal advises they do so. Where that isn’t an option, he said a grower’s best option is to proactively trap, and spray when necessary.

“At this point, the best thing a grower can do is to put out traps starting in mid-March and see whether they see any activity,” Rijal said. “If they see anything that is alarming, they need to be in contact with their PCA and make a decision whether to treat or not, what to use and the timing.”

Controlling the pest is difficult, Rijal noted, primarily because of its ability to switch hosts and move from an orchard into nearby shelters or other host plants. Pyrethroid insecticides, for example, which are the most effective compound currently available for controlling BMSB, will knock down the population, but only for ten days or so, after which the BMSB will return at infestation levels equal to or greater than before the treatment. Also, he said, the broad-spectrum insecticide can harm populations of beneficial predators, disrupting integrated pest management programs.

Still, he said, at times a pyrethroid may be a grower’s best option. He added: “In California, crop damage (from the pest) is new, and we are still working on providing recommendations if growers need to treat.”

Rijal cautioned growers from treating orchards simply because they suspect they have a problem with BMSB. “It is critical to put the BMSB traps out, do the scouting of the orchard for live bugs and damage, and follow the control activities, if warranted, based on your trap counts and scouting activities,” he said.

To supplement the use of insecticides, researchers are studying alternative methods for controlling the pest, including the samurai wasp, or Trissolcus Japonicus, a parasitoid that attacks the eggs of BMSB and that has been found in Los Angeles County. More recently, they have been researching the viability of incorporating into control measures a microsporidia pathogen, Nosema maddoxi, that Cornell University researchers found was crashing BMSB populations in labs.

Peter Shearer, an entomologist for the Strawberry Center at Cal Poly, who started working on BMSB while he was at Rutgers University in 2003, just five years after it was first found in the U.S., said for years researchers were stumped as to why populations sometimes crashed in laboratories. “It turns out it was this microsporidia pathogen, Nosema maddoxi,” he said.

Shearer, who continued to study BMSB for several years while he was at Oregon State University, said he believes BMSB could be a long-term pest in California agriculture, but added a caveat.

“The population south of Sacramento and in Sacramento and in the almonds has persisted, so I would say, yes, it is adaptable to our climate,” Shearer said. But, he said, there are pockets on the East Coast, such as in coastal areas of North Carolina and Virginia, where it has not been found, giving rise to hopes it may not be adaptable to the Central Valley’s heat.

“We don’t know why it hasn’t established in those areas,” he said. “Not even the experts over there know. Maybe it is too hot.” In keeping with Shearer’s caveat, Rijal speculated that its slow rate of migration into commercial crops could be the result of the Central Valley’s heat.

“Establishment wise, it is not spreading like it has on the East Coast and in Oregon,” Rijal said. “That could be because our summer temperatures and climate are completely different. We are dry and hot. And although BMSB might be adaptable to those kinds of environments, maybe it just takes a little more time. We just don’t know.”

Rijal added that while the pest has flourished in cooler areas of Europe and in the country of Georgia, where it is a serios pest in hazelnuts, BMSB has not been found in extremely hot areas, such as in areas of South America. The pest is native to China and occurs in Korea and Japan, as well.

As to whether the pest poses a problem for other tree nuts, such as pistachios, Rijal said research suggests it does.

“Based on lab work in Riverside and in the Kearney Ag Center in Fresno, we know that they feed on and can damage on pistachios,” Rijal said, “but we have not seen the population in commercial pistachio orchards yet.”

To date, researchers also have not seen damage in walnuts.

At this point, Rijal said, BMSB is established in urban areas of several counties in the Central Valley, including from Glenn to Fresno. He added, however, that damage to crops has not been reported to date, except in the northern San Joaquin Valley, where BMSB is damaging peaches, as well as almonds.

“Whether it will be established in orchards throughout California, we aren’t sure of that at this point,” he said.

One thing he is sure of is that growers need to keep an eye out for the pest and be prepared to respond if necessary. He added that clear sticky traps with a BMSB lure are commercially available.