Self-fertile almond varieties that don’t require a pollinizer, need fewer or even no beehives to set a crop and allow one-pass harvests are gaining market share as growers look to maximize profit per acre.

Although there will still be a place for varieties, such as Nonpareil, that have unique kernel characteristics but require a pollinizer, industry leaders say self-fertile varieties are here to stay.

Independence, a self-fertile variety developed by Zaiger Genetics and licensed to Hickman-based Dave Wilson Nursery, entered the market about 15 years ago. Since then, acreage has continued to increase and now accounts for about 2 percent of California bearing almond acreage and 24 percent of non-bearing acreage, according to figures from the 2019 California Almond Nursery Sales Report, the most recent year for which data is available. That compares to Nonpareil, the most widely planted variety, with 37 percent non-bearing and 39 percent bearing acreage.

“It looks like there’s a bit of a plateau in the last data. In previous years, (the Independence acreage) had been going up and up and up,” said Franz Niederholzer, a University of California Cooperative Extension farm adviser in Colusa County and research coordinator at the Nickel’s Soil Lab in Arbuckle. “There will be a lot of Independence in the market in the next two to three years, so we’ll see how the pricing looks going forward.”

He was referring to Independence’s kernel trait and handler pricing, which typically puts it between California varieties and Nonpareil.

Shasta is a relative newcomer from Oakdale-based Burchell Nursery, accounting for only about 3 percent of non-bearing acres and few bearing acres, according to Almond Board figures. It, too, is gaining popularity, said Robert Gray, a Burchell sales representative for Modesto and west Stanislaus County.

“We’ve seen a lot of interest,” he said. “It’s actually becoming our top almond variety as far as orders.”

Handlers consider its kernel a California-type similar to Monterey or Carmel and price it accordingly, Gray said.

Varieties in the Pipeline

Several other self-fertile varieties are in the pipeline from Zaiger, Burchell, the University of California, Davis, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service.

“There’s a lot of interest, and I think this is going to be the future of the industry,” said Roger Duncan, a UCCE farm adviser in Stanislaus County. “We expect year in and year out over the long term to see more consistent yields and better set in years where there’s less bee activity. So I think this is the wave of the future and certainly is a major emphasis of most breeding around the world and in California.”

That’s not to say breeders will forget about more traditional varieties, especially in light of global climate change, water shortages and ever-changing markets, said UC Davis breeder Tom Gradziel.

“The new challenge is to develop self-fruitful as well as more traditional varieties to meet these novel, and sometimes poorly characterized, needs,” he said. “The good news is that the efforts required to bring self-fruitfulness from wild almonds and peach have also brought in novel genetic options that have promise to meet these novel industry needs.”

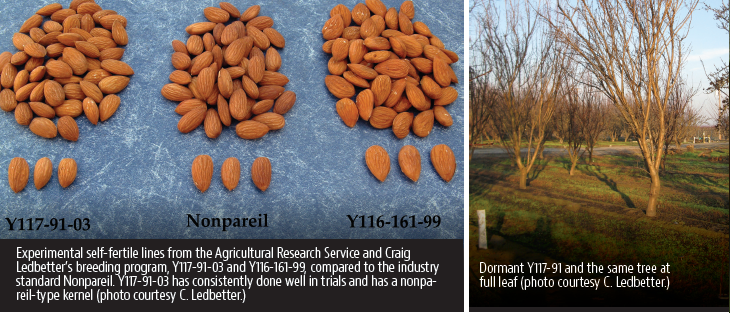

As part of his work, Duncan is conducting one of three regional UCCE variety trials. The study near Salida is similar to ones conducted by Farm Advisors in Butte and Madera Counties. Of the 30 experimental varieties, 10 are experimental self-fertile lines from UC and ARS. Not included in the trial are Independence and Shasta. Now entering the seventh leaf, some self-fertile varieties have performed better than others.

“We’re still in the process of evaluating all of these things – time will tell,” Duncan said. Before any are released, several years of production data is needed. That is on top of screening early crosses to weed out ones with little potential. Altogether, it may take a breeder 10 to 15 years – and sometimes longer – to develop a new almond variety, he said.

Of the four USDA varieties in Duncan’s trial, ARS breeder Craig Ledbetter said three have looked good and will be sent to the Foundation Plant Service to be screened and cleaned of any plant viruses before they’re eligible for release. The process will take a couple of years, after which the numbered experimental lines will be given variety names.

Although the regional trials are funded by the Almond Board, Ledbetter’s breeding program is federally funded.

UC’s Gradziel has more than 20 advanced selections of self-fruitful almonds that have been tested for 10 years or more.

Fewer Bees, Single Harvest

Bob Livak, who farms with his son, Keith, near Hilmar, liked what he saw in Shasta and ordered trees to plant 10 acres.

“They’re self-fertile – I’m looking at less bees and one harvest. Those are two big factors,” he said. “I do love the one harvest.”

In another orchard by his house, Livak has three varieties, and he joked it seemed like he was harvesting from mid-August to mid-October.

Based on reports, he said Shasta tends to also yield well. In addition, everybody he knows who has the variety has said they’re easy to shake during harvest and winter sanitation. Another characteristic Livak liked was the variety’s low chill hour requirement.

“With our so-called climate change, we’re getting warmer,” he said. “If we need a tree for the future, maybe we need one that doesn’t require as many hours.

To Bee or Not to Bee

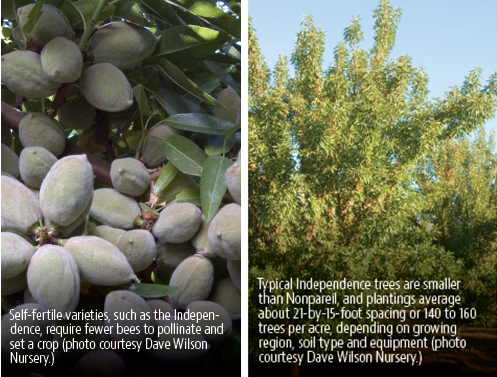

While Burchell Nursery recommends a half stocking rate of bees – or about one hive per acre – for Shasta, Dave Wilson Nursery said no bees are needed to pollinate Independence. Nevertheless, questions remain about whether placing a reduced number of hives, such as 0.5 hives per acre, increases yields compared to no hives.

Harbir Singh, Northern California sales representative for Dave Wilson Nursery, said his research has shown Independence yields are similar with and without bees. But he said some growers still use a reduced number of hives to appease insurance and their neighbors.

Duncan is currently conducting a field trial to try to answer the bee question. It involves enclosing Independence almond trees with screen cages to exclude honeybees.

“We had a very significant increase where we had bees present compared to where we didn’t,” Duncan said, adding he plans to expand the trial this year.

Another advantage of planting a solid block of a self-fertile variety is uniform timing for cultural activities, he said.

“You have one bloom to cover, one hull split spray period to cover, one harvest operation, fewer bees required – so it’s cheaper to farm that way,” Duncan said. “We also would expect through the years you would have a more consistent yield.”

Cutting equipment passes in half during harvest also will help growers significantly reduce the amount of dust produced, Duncan and Niederholzer agreed.

Independence

Independence trees tend to be slightly smaller than, for example Nonpareil, especially if they’re grafted onto standard sized rootstocks like Nemaguard, Lovell, Atlas, Viking or Krymsk 86. As such, growers may lose out on yield potential if they plant them on traditional Nonpareil spacings, Niederholzer said.

Dave Wilson Nursery has increased production of Independence grafted onto hybrid rootstocks, such as Hanson, that result in a larger tree. Jereme Fromm, Dave Wilson Central California sales representative, said typical Independence plantings average about 21 by 15 feet or 140 to 160 trees per acre, depending on growing region, soil type, and equipment.

And depending on those factors as well as fertility, Independence trees may begin bearing a crop during the second leaf. But Singh said growers would be wise to remove the crop and wait until third leaf to let the trees funnel more energy into building a stronger architecture and taller tree. In addition, two-leaf trees aren’t sturdy enough to take mechanical shaking, and growers who do so risk permanently damaging the tree.

Initially after Independence was released and trees came into production, some growers reported difficulty shaking and removing the nuts. Through trials, Singh said, they found that applying the bulk of the season’s nitrogen early significantly reduced the stick-tight problem. In the southern and central production areas, growers should not apply nitrogen after the end of April. In the northern area, the cutoff is May 15. Growers can still apply all other macro- or micro-nutrients as needed, he said.

Shasta

Burchell Nursery offers Shasta grafted onto both peach and hybrid peach-almond rootstocks, Gray said. The self-fertile variety tends to be precocious, meaning it comes into production early and produces a heavier crop earlier.

Shasta trees are semi-upright to spreading, having a structure similar to Monterey. Because of that, he said growers should tie the scaffolds from the first through second or third dormant season.

The variety leafs out as it blooms and will be one of the last varieties to drop leaves in the fall, Gray said. The nuts, which shake easily, mature at about the same time as, or slightly ahead of, Nonpareil.

Most Shasta orchards are still in their third or fourth leaf. But an eighth-leaf orchard in Salida with 138 trees per acre yielded 3,145 pounds per acre, and a sixth-leaf orchard in Firebaugh with 135 trees per acre produced 3,694 pounds per acre, according to Burchell Nursery information.

Factor in Your Risk Tolerance

Regardless of the new variety, Duncan and Niederholzer said growers should first ask themselves how much risk they’re willing to take before deciding to plant one.

“For big growers, it makes sense to be looking at everything because they plan to be in the business for a long time, want to stay up on new stuff and can afford to take a relatively small loss if it doesn’t pan out,” Niederholzer said. “If you’re a small grower, say 20 acres, the self-fertile varieties make perfect sense mostly because it’s easier to get someone to custom farm them. But those people in the middle who are professionally farming have to ask themselves how much can they afford to lose because it’s possible for a new variety to not prove out.”

“We’re only 10 to 12 years into Independence and just barely on the road with Shasta. There’s a lot of interest in a lot of new stuff, but we also have 50, 60 and 70 years’ experience with varieties that are proven winners.”