In this article, I explore the use of insecticides and their proper timing to augment sanitation in almonds to improve control of navel orangeworm (NOW). Before proceeding, I would like to alert you to an amazing piece of technology that can impact insecticide performance. This technology is often overlooked and/or taken for granted, yet millions of dollars and countless man-hours were spent on its development. This technology is called the product label. Carefully read the label.

In addition to the safety data and maximum application rates specified by law, it is important to consider the range listed on the label for the target insect and commodity. Insect species differ in their sensitivity to all products and a maximum rate for one pest may be an intermediate rate for another. To optimize performance, start at the maximum level allowed. You can consider backing off the maximum rate when you consistently achieve your desired results. Tree nuts are especially challenging because any insecticide that does not contact the nut is a miss, although it remains in the canopy. In my experience, the best results occur when the droplets are concentrated. This article reports research on mummy sprays conducted in collaboration with Dr. Garrett Gilcrease from Syngenta US between 2016 and 2020. Before proceeding further, I note that as a federal researcher, I do not endorse specific products, but I do use their names if they were part of my studies.

Sanitation is Foundation

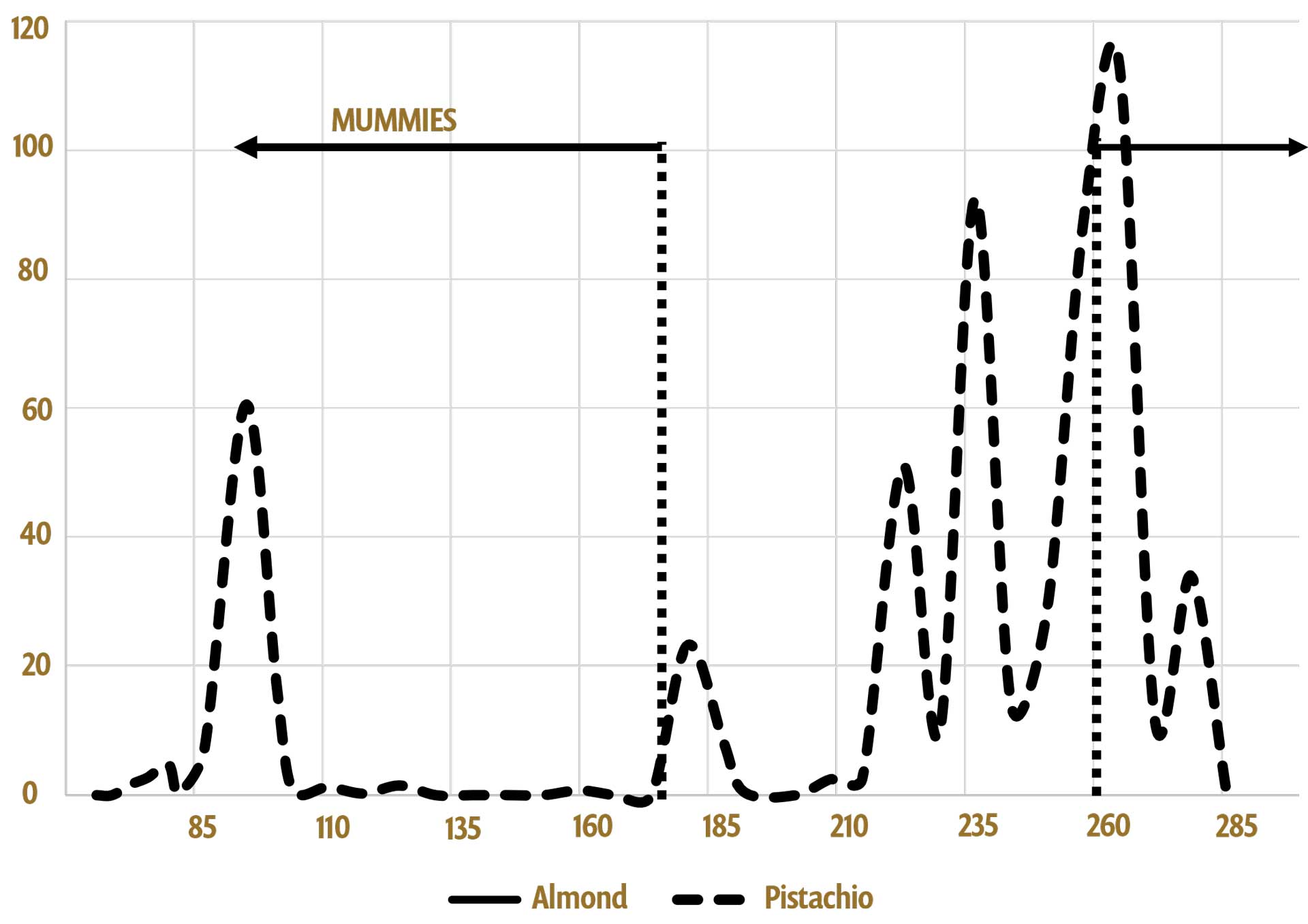

Sanitation is the foundation for control because mummy nuts serve as both harborage and a food source for NOW, which may utilize mummies for up to 75% of the year. In Figure 1, a representative graph from 2017, there are at least four emergence peaks from mummies, demonstrating considerable cycling on these nuts. Sanitation at times may be inadequate due to several factors, alone and in combination, including wet conditions during late fall/winter and excluding shakers and hand poling crews from the orchards, stick tight nuts, the cost and availability of labor, and the predicted price of almonds limiting the budget. Several outbreaks of navel orangeworm occurred in almonds since 2012, most recently in 2017 for all tree nuts. The outbreaks coincided with high densities of mummies left in the canopy, and although this high carryover was recognized early in the season both years, many growers failed to change their management plans and suffered high damage.

Applying insecticides to mummy nuts is a simple strategy to mitigate sanitation failure, yet there are barriers to its adoption. First is the fear of mite flareups, although selective insecticides can be used. Second is the cost of an additional insecticide application, which can exceed $60 dollars an acre depending on the insecticide chosen.

Third is the mistaken belief that the goal of a mummy spray is to kill larvae already infesting the nuts, which is ineffective. In my research, when I hung laboratory infested pistachios in trees and then sprayed them with Warrior® (pyrethroid), at best I achieved 50% mortality. This is higher than I expected and only occurred because the nuts were so heavily infested that some larvae were webbed on the outside and vulnerable.

Fourth, many potential users are unaware of, or do not fully understand, the benefits of coating the mummy with an insecticide which kills the egg when absorbed through the shell. Newly hatched larvae are also killed by contact as they crawl over the hull or killed by ingesting insecticide when they feed. Eggs do not have to be directly sprayed for the application to be successful. Remember that egg hatch is dependent on degree day accumulation, and it takes 100 degree-days (Fahrenheit) for an egg to hatch. At the height of the summer, an egg hatches in 3 to 3.5 days, while in April or even May it may take ten days or more for the egg to hatch (my record is 30 days for eggs pinned to mummy almonds on February 1.) Depending on the year, a spray made in late April or early May can eliminate eggs laid ten or more days before the application, thereby having a large impact on existing eggs.

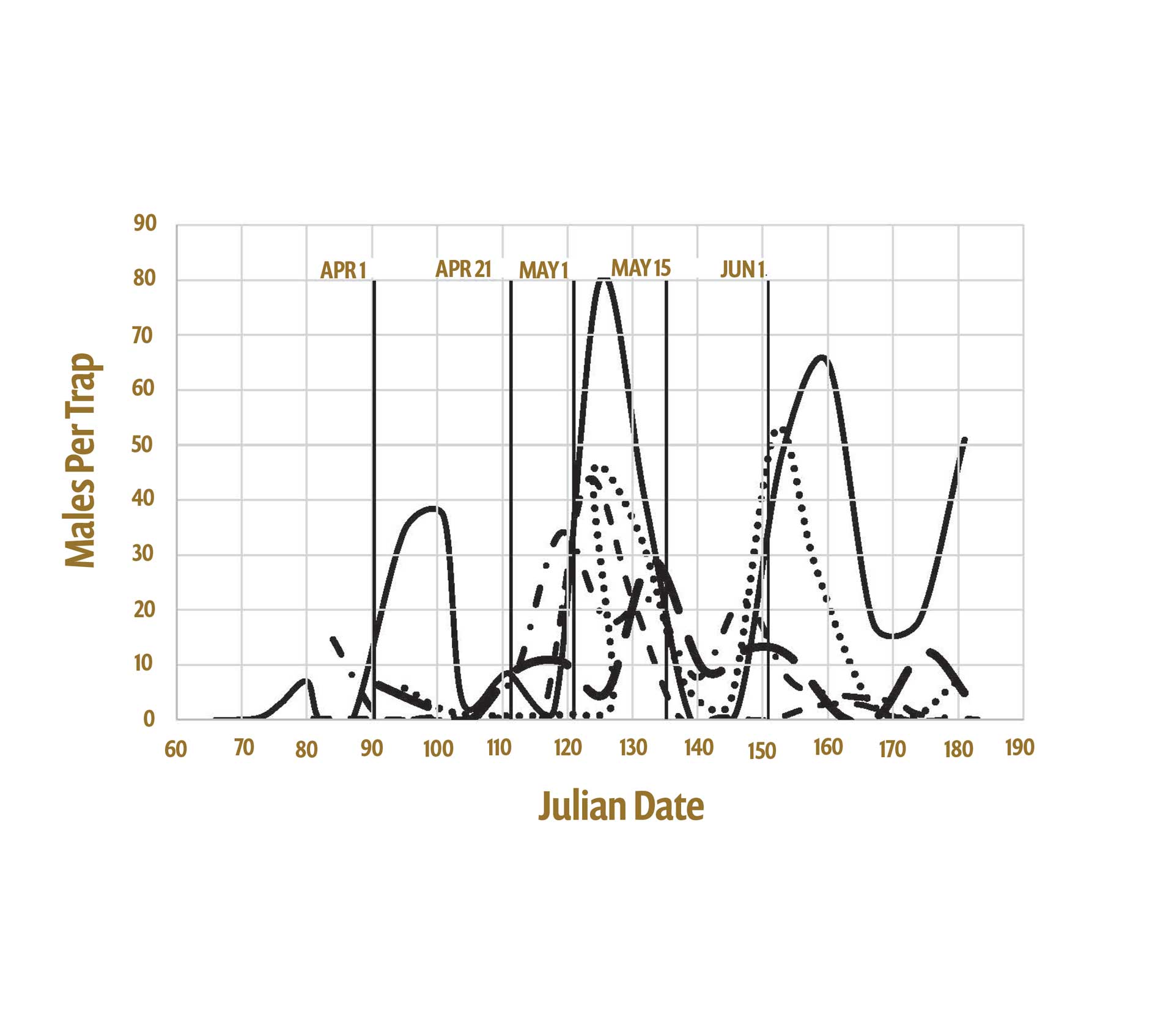

Fifth and finally, there is uncertainty about the proper timing of a mummy spray and its duration of control because of the protracted NOW adult emergence from late winter (Julian date 60; March 1) through the beginning of summer (Julian date 180; June 29), a period of 120 days as illustrated in Figure 2 (2017-21).

Timing

Over 120 days, adults emerge sporadically from almond and pistachio mummies, with peak emergence occurring from April 25 to May 15 (Julian dates 115 to 135) (Fig. 2). This interval can be divided into two parts based on host availability. In the first part, March through the third week of April (Julian dates 60 to 111), mummies are the only resource available for oviposition. The eggs laid during this period produce females that emerge during the last week of May through mid-June (Julian dates 145 to 166). These females in turn must lay eggs on mummies again and their generation time is longer and survival lower due to the decreased nutritional quality of the nuts. Adults from this cohort/group typically emerge in August.

During the second part, from the last week of April through June (Julian dates 114 to 181), females must still lay eggs on mummies, but their offspring that emerge in late June through July can oviposit on either mummies or new crop Nonpareil almonds. The females that cause initial damage at hull split originate from eggs laid between late April through May. 35% of the entire overwintering flight occurs in May, 55% of the entire overwintering flight occurs between April 15 and June 1 (Julian dates 105 to 152), and 75% of adult emergence occurs from April 15 through June 30 (Julian dates 105 to 181). Figure 2 clearly illustrates the critical period between April 21 and May 15 (Julian dates 111 to 135). An insecticide applied in mid-April with a duration of control of six weeks or longer can affect the oviposition of females circulating during this period. To repeat, this is a mid- to late April spray and should not be confused with a May spray; application in mid-May clearly would miss most of the flight. Although the graphs depict male capture, females are flying at the same time, and it should not be a surprise that the solid black line with the highest peaks in Figure 2 is from 2017.

Insecticide Choice

Over the period of 2016-20, we evaluated five insecticides as mummy sprays: Altacor®, Besiege®, Intrepid 2F®, Minecto Pro® and Proclaim®, and I also evaluated SpearLep®. All insecticides tested, both single ingredient and premixes, provided a duration of control extending beyond four weeks. In one experiment evaluating Besiege®, Intrepid 2F® and Minecto® Pro, all provided control for 70 days. At that point, while Minecto Pro® still reduced survival by 48%, both Besiege® and Intrepid 2F® reduced survival by more than 77%, suggesting that their duration of control extended beyond ten weeks. Intrepid 2F® also had substantial contact toxicity that was stable for four weeks.

Mummy sprays last longer than new crop applications because their goal is not as challenging. These late April sprays only need to kill the navel orangeworm before it emerges as an adult from the nut, and the extent of feeding is irrelevant. In contrast, an insecticide protecting a new crop nut must kill the larva before feeding damage occurs; death or paralysis of the larva at the first bite is the goal if the larva reaches the kernel.

In summary, sanitizing mummies by removing them from the tree and destroying them on the ground is preferable, but when this cannot be done, applying selective insecticides can mitigate sanitation failure. The spray should be applied during the period from early to mid-spring (April 21 to May 5). I refer to this application as a mummy spray to differentiate it from other insecticide applications applied in May. When insecticides are applied, it should be at the highest label rate to maximize their duration of control.

Mummy sprays target both eggs and newly hatched larvae and their goal is to disrupt oviposition, either by killing eggs laid on the hull/nut by absorption, newly hatched larvae by contact as they crawl on the surface of the nut, or newly hatched larvae when they feed on the nut. Both single ingredient and premix insecticides were equally effective as mummy sprays, and the most consistent results were obtained with Intrepid 2F (IRAC Group 18, diacyl hydrazine) and Besiege (IRAC Group 28 diamide + IRAC Group 3A pyrethroid). Use the highest label rate to maximize the duration of control. Rotation with a different insecticide family for the hull split application is essential to prevent exposure of successive generations of NOW to the same insecticide family.