Historically, almonds were a dry land crop in California. In the foothills, there are still old almond trees on almond rootstocks, according to Tom Gradziel, plant science professor at UC Davis.

In California, dry land almonds were raised on the foothills for two reasons, Gradziel said. “You want air drainage because of the frost, but also you need water drainage because almond roots grow so deep that they are susceptible to waterlogging”

Except for California and Australia, other almond producing countries started out as dry land, Gradziel said.

Spain recently started modeling California’s high-input/high-return irrigated production, but their water is drying up faster than California’s. Now, there are Spanish growers taking a hard look at their almond production and saying, alright, where’s that sweet spot between full irrigation and dry land production or they go to Portugal to grow their almonds, Gradziel said.

Physiology of Almonds

“Almond is hugely adapted to dry land. It’s historically been a dry land crop,” Gradziel said.

Almond root growth, like the almond tree, is very aggressive. They mine the soil very well and go deep and wide to reach the marginal water from the rain, so through the summer they can survive with just rainwater, even in a drought year, Gradziel said.

But almonds flower in February, so the tree starts to push, and if there is flooding, it could die. “You flood those roots, those roots asphyxiate, they die, disease comes in and your orchard’s mush,” Gradziel said.

High Input/High Return

“What many people don’t realize is California rules almond production because California took it off that old scenario of low-input marginal land, no irrigation, dry land farming low returns, to high input/high returns,” Gradziel said.

“If you go over to Spain, or Greece, you’ll see almonds still mostly growing on the marginal land. They’re not going to get a big crop, but they’re going to get something,” Gradziel said.

Dry land almonds on almond rootstock don’t tolerate the sometimes-saturated valley soils. Because of this, Central Valley growers switched to a peach rootstock, and in the Sacramento Valley where there’s more water, a plum rootstock.

“It was really a revolution to put almonds on peach rootstock. It totally changed the paradigm and made it a high-input/high-return crop,” Gradziel said.

Reverting to Dry Land

Is it feasible for California growers to revert to dry land? “That’s sort of an unknown. We’ve got some trials going now where we’ve got dry land almonds,” Gradziel said, adding one of the trials is in the Capay Valley.

“You’ve still got growers in some of these isolated areas in Capay Valley that are still growing almonds dry land. Sometimes 100-year-old trees, 80-year-old trees, very big trees, very deep roots. Maybe a third of the trees are gone, but since it’s low-input, any return you got is a bonus,” Gradziel said.

Gradziel has some experimental, mostly seedling plots for dry land conditions on a small scale. “As an example, two years ago I had some germinating seed on controlled irrigation, and then I forgot to put it back on the main irrigation. So last year, come August, I realized that these seedling trees, and they are about maybe six feet tall at this point, they weren’t on our irrigation. They weren’t getting any irrigation water, except that December rainfall, which was a drought year, and I still had 90% of the trees survive,” he said.

If growers returned to dry land, they would need to slow the tree down, particularly in the heat of summer. This might be accomplished by using almond rootstocks. Peach rootstocks or any combination of the peach-plum, peach-almond hybrids invigorate the tree, which is why they have such high yields and growth.

“An almond tree on an almond rootstock can, at least in theory, and some of our data supports this, put that tree in a growth dormancy and shift that balance toward nut production and away from runaway growth,” Gradziel.

“There’s some evidence out of Spain, and some of the early work that we’ve done here, where if you grow almond on low water, say, a dry land type scenario on an almond rootstock, in the summer it’ll go into a natural summer dormancy,” Gradziel said.

“In a sense, what you’ve done is you’ve tweaked the equation to your advantage. You don’t necessarily want a lot of new growth. Once you’ve got a productive orchard, you don’t want it to keep growing aggressively. You want it to settle down, get into that spur production, and produce nuts rather than lots of new shoots,” Gradziel said.

“In many crops, that would catch up with you because you need those new shoots, to get the new flowers, to get the new crop next year. But when you have a high-spur-bearing crop like almond, you only need millimeters of new spur growth rather than feet of new shoot growth,” Gradziel said, and limited growth also means less pruning.

“If we put an almond rootstock in a valley soil, it’s going to put down very deep roots, and consequently it’s going to be very susceptible to water logging, and every five years or so when we get that El Niño, we could have massive tree dieback,” Gradziel said.

The northern San Joaquin Valley has sandy soils, which has better drainage, Gradziel continued, so it might be possible to dry land almonds there. “If we have some of the better-trained areas in the Westside or even some of the sandier parts within the valley, there may be opportunities to dry land.”

Potential Benefits to Dry Land Almonds

There are several benefits to farming dry land almonds.

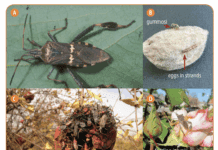

“In general, many of the diseases that are problematic for us would be less of a problem in dry land. And the same goes with the pests,” Gradziel said.

With dry land, mites could be more problematic, and there will be more traditional dry land pests than wet weather pests, irrigated pests, Gradziel said.

While the nuts are smaller, the flavors are enhanced, Gradziel said. “A lot of dry land farmers would say that they greatly prefer the taste of a dry land [almond] as opposed to commercial.”

Dry land will also have low fertilizer usage, which is an advantage from the environmental side, Gradziel continued.

Shaker damage makes the tree susceptible to canker, so by 20 years, 10% or more of the trees can be lost, which is a big hit on potential yield. Dry land, in comparison, has much less tree loss, and it’s not unusual looking back to the mid-1900s to see orchards that are 40, 50, 60 years old or more and still have trees in production, Gradziel said.

There is less shaker damage with dry land almonds. “The danger of harvesting with shakers is that if you’ve irrigated too close to harvest you’ve still got a lot of moisture in the bark, and your bark gets bruised and damaged, and then you’ve got canker and disease coming in. In a dry land, your bark is going to be much more resistant to the shaker damage,” Gradziel said.

Dry Land Almonds in Spain

Spain has been farming dry land almonds for centuries, according to Dr. Ignasi Iglesias, Ph.D., technical manager of Agromillora Group.

Typically, Spanish almond growers have produced dry land almonds. “Only in the last two decades has irrigation been really important,” Iglesias said.

“Currently [2021], most of the almonds in Spain were cultivated in dry land, accounting for 612,227 hectare (ha),” Iglesias said, compared to irrigated almond about 132,239 ha.

No specific varieties have been developed for the dry land almonds in Spain, Iglesias continued. The main objectives of the Spanish breeding program have been to develop late blooming varieties to avoid spring frost and self-compatible to avoid problems with pollination.

“In addition to low-density plantings compared to irrigated plots, an indirect way to avoid a major stress of the trees in dry land has been planting varieties with early maturity such as Guara, Vairo, Lauranne, Penta or Vialfás, all hard or semi-hard-shell varieties with less issue with pests. And this combined with late-blooming varieties, as far most of traditional and new dry land almond areas are exposed to recurrent spring frost,” Iglesias said.

Specific Needs

Do dry land rootstocks require specific soils? Iglesias offered a three-part answer.

First, for dry land to be profitable for almond production requires non-marginal soil conditions to capture 100% water and a rainfall up to 400 millimeters (mm) a year with good spring-autumn distribution as the main factors. So, it means specific soils.

“The ideal ones should have a high capacity to store water (deep soils) in autumn-spring. These are the soils, for example, where the grapes also have the best performance, those will be the ideal,” Iglesias said. “Also, the soil management is crucial during the June-September period (no rain). The weeds are mechanically eliminated, maintaining a clean soil surface after blooming to optimize the water availability.”

Second is rootstocks. “As dry land has been the most common, some selections of almond as the cultivar Garrigues have been used traditionally as a rootstock because the root system of the almond is the most tolerant among the Prunus species to drought. In the last two decades, the peach-almond hybrid GF-677 from INRAe (France) has been widely used in almond and peach because of its high vigor and good tolerance to drought,” Iglesias said. “Also, the hybrid Garnem (Garfi almond x Nemaguard peach rootstock) has been developed during the last decade but used less than GF-677 in dry land.”

Third, is an option developed by Agromillora in recent years: self-compatible varieties for dry land, in particular, Penta, Lauranne and Vialfás. “The key is combining the good tolerance of the almond root system producing plants by invitro propagation with a specific training system: a small hedge similar to one used in irrigation, but with a superior spacing (4.0m x 1.5m to 2m) and a smaller individual tree canopy, similar in total volume per ha to the traditional open vase but adaptable by mechanical pruning to specific climatic/edaphic conditions of each area, and full mechanization of pruning and harvest (over-the-row machine). We don’t want and don’t need necessarily a lot of growth to be efficient in terms of yield,” Iglesias said.

The downside to dry land is less yields. A good plot in dry land with a well distributed rainfall of around 400 to 600 mm of rain per year can get 500 to 700 kilograms of kernel per ha, which is four times less of what irrigated almonds receive. But the price is more than twice that if growers raise dry land organic almonds.

“The important thing in Spain is that around 80% of the organic almonds produced are produced in dry land because in these climatic conditions, and in particular, if we are located in the Mediterranean Basin, it is much easier to produce organic because there is less incidence of disease,” Iglesias said, adding there were approximately 148,000 ha of dryland organic almonds in 2020, most of them located in the mentioned Basin.

The best scenario for growers is combining dry land and organic when possible, but not all growers are ready to transition, Iglesias said. “For example, it is very difficult to produce organic almonds in irrigated land of Andalucía, Extremadura (Southwest Spain) or central Portugal (Alentejo region).”

- Iglesias listed the benefits of dry land:

- Low input and low cost of production

- Reduced pest and disease pressure, so more appropriate for organic production

- No irrigation system or water and pumping costs

- An interesting alternative in a scenario of water scarcity by using a support irrigation system to optimize the tonnage per foot of water

- Positive impact in the environment as CO2 sink compared with annual crops as cereals combined with an increase in the efficiency of inputs use (labor, plant protection, etc.) when small canopies from self-rooted trees are used

- The main benefit would be dry land almonds in optimum climatic/geographic conditions because yields will be almost dependent on rain and convert to organic production.

Analyzing Dry Land Production

Sebastian Saa, associate director of agricultural research with the Almond Board of California, went to Spain in April to gather information and learn about different production approaches.

“Dry land is an interesting topic that is not easy to analyze, and it should be analyzed very carefully when an investor or a new grower is planning to go that pathway. I would say, the first thing to consider is that it is truly a different game,” Saa said.

Dry land is a game of cost inputs, Saa continued. “It’s a very low-input-cost, low-income-cost model where yields are very low, and the tree depends 100% on the water that is captured in the soil via rains.”

The average yield is 100 pounds per acre, Saa said. “I’ve seen orchards that are located in some specific locations that have 12 inches of rain, and then the trees have some water to produce more fruit, and they can reach up to 600 pounds per acre, but that’s also with very good management,” Saa said, using a low-input/low-return system.

In Spain, the trees are planted at a very low density, 28 to 40 trees per acre. This allows the trees to have enough space to grow a big root system and capture a lot of water, Saa said.

They use self-compatible varieties in Spain, and bees aren’t used because they are cost prohibitive. Trees are planted in more marginal soils, and they plant hard-shell varieties that have less issues with pests, Saa said.

“It’s a different model; very low-input, low-cost model, and also, of course, lower revenue per acre,” Saa said.

Is this something we can copy and paste in California? Saa says no.

“We have different realities, but we may have some areas, some niches where we could try this.”

The first thing for anybody that is seriously thinking about this is to put together a financial analysis with a technical expert to predict the cash flow and calculate internal rate of return, Saa said.

To make dry land almonds pencil out, growers would have to look at ways to eliminate or significantly reduce inputs. “It’s far more expensive to have 100 trees per acre than 28 trees per acre,” Saa said, adding the same with bees; it’s more expensive to have bees and soft-shell variety that are more sensitive to insect damage than a hard-shell variety that is self-compatible. Also, land that has no water is more cheaper than land that has access to water.

To raise dry land almonds, growers have to move from a high-input/high-return to low-input/low-return or to a medium-input/medium-return horticultural model, Saa said.

Determining a Profitable Crop

Determining how a crop is profitable may change. It’s not about yield per acre any longer, it’s the yield per foot of water, Gradziel said.

“That’s where we’re going in the future, and in that scenario, definitely looking toward lower water inputs has advantages.

“But again, this whole change may be predicated upon transitioning to an almond or almond-like but flooding-tolerant rootstock,” Gradziel said.