The recent series of atmospheric rivers have dumped enough rain and snow on Northern California to give us hope that the end of the drought may be near. California’s Department of Water Resources is reporting that Central San Joaquin precipitation at the end of January was 177% of normal, year-to-date, and 84% of normal for the entire water year with two potentially wet months still ahead. According to Department officials, the 2022-23 water year, so far, is “the best start to the snowpack in over a decade.”

Additional evidence of this year’s water supply bounty is the tremendous amount of water flowing through the Sacramento/San Joaquin Delta out to the Pacific Ocean. The region depends on this outflow for ecosystem health and to reduce salinity in the Delta where many Bay Area communities get their water. The amount of outflow was so abundant in early January news writers throughout California were asking why more wasn’t being done to capture the abundant supplies.

That’s the good news.

The bad news, especially for communities in the San Joaquin Valley, millions of acres of the country’s most productive farmland, and the consumers who depend on it, is that we aren’t doing enough to capture these flood flows when they’re available. That’s because a set of calendar-based regulations set limits on how much water can be captured, even if trees are being toppled and water is flowing over the banks of creeks and streams.

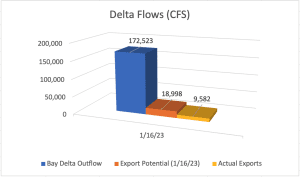

On Jan. 16, Bay-Delta outflow peaked at over 172,500 cfs (cubic-feet per second), while export pumping had ranged from just 6,500 cfs to about 8,500 cfs due to environmental restrictions intended to protect Delta smelt. That day, exports began to rise, reaching near capacity of 13,890 cfs on January 24. If water system operators had the flexibility to safely increase pumping earlier in the month, an additional 200,000 acre-feet could possibly have been captured and stored for use later in the year.

The rule preventing us from saving more of this near-biblical amount of water is based on fish behavior under certain historic conditions. However, we are clearly living through exceptional circumstances, and the rules and rule makers are utterly incapable of adjusting, which could be the difference between these storms taking us out of drought instead of suffering through another dry year.

Instead of relying on real-time data, like almost all other decisions we make, California’s water regulators are held to a specific set of rules based on arbitrary dates on the calendar or one-time occurrences in the Delta. The pumps that are in place to deliver water to farms, homes and businesses are currently running at half of their capacity, even though billions of gallons of water are flowing out to the ocean, far more than the State’s environmental regulations require.

As California struggles to recover from three years of intensive drought, and the San Joaquin Valley desperately tries to restore its groundwater supplies, this management of such a scarce resource is mystifying given how much water is available right now.

Anyone who has spent enough time in California understands how fickle our water supply can be. Our changing climate is delivering wetter wet years and hotter dry years than in decades past. There are enormous opportunities to build the infrastructure needed to capture flood flows like the ones we’ve experienced so far this year.

Both the state and federal governments have made funding available to repair our existing infrastructure and to build new projects, such as wisely placed new or enlarged reservoirs to capture high storm flows like the ones we saw in January. New canals and pipelines can carry the water we’ve saved to areas in the San Joaquin Valley where they can be stored underground, replenishing the region’s groundwater.

Diverting water during these peaks gives us the opportunity to share in the abundance that is benefiting California’s natural environment. The fact that we can share this abundance also provides the necessary resources to keep our farmers farming and delivering the safe, local and affordable food California families depend on when they visit the grocery store.

And we need updated policies and projects designed for the 21st century, with functional flows, new spawning areas and habitat for young fish instead of a calendar-based approach funneling flows through channelized water ways that provide little if any ecosystem benefits.

Rather than accepting our changing climate as an inevitable path to scarcity and relegating vast parts of our state to perpetual water shortages, we believe better, science-based management is the key to future water supply abundance for all Californians.